Dear Language Nerd,

As often happens, I recently preceded an observation with “I wonder what….” I frequently see that sort of thing with a question mark at the end, but it’s obviously not a question. Equally obviously, a question is implied. So my question to YOU is: I wonder what the term is for this kind of question/statement?

-Laura

***

Dear Laura,

It’s an open interrogative subordinated finite content clause.

Or, if you prefer, an embedded question. We’ll take that nomenclature step-by-step, but first, a shout-out to Mobile Public Library for getting hold of Huddleston and Pullum’s Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (the big one) for me and making this post possible. I <3 y’all.

This post is about stuff you do all the time without ever thinking about it, assuming you’re a native speaker of Standard English. But I’m gonna walk us through it all anyway, even parts that may seem super obvious, so we’ll all be using exactly the same labels for exactly the same things.

Hey, you’re the one that asked about terminology. That requires precision.

The Main Event

So, what’s a clause? Fundamentally, it’s a verb and whatever that verb demands. See, verbs are the boss; verbs get what verbs want. And verbs always** want a subject to come before them, even in the smallest clauses:

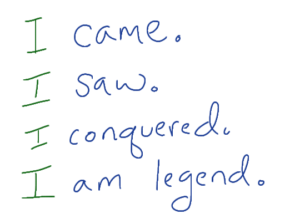

Four complete main clauses. Four different verbs with the same subject, “I.”

Four complete main clauses. Four different verbs with the same subject, “I.”

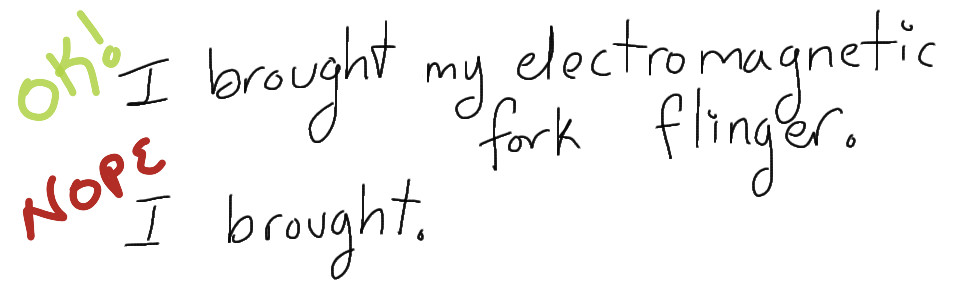

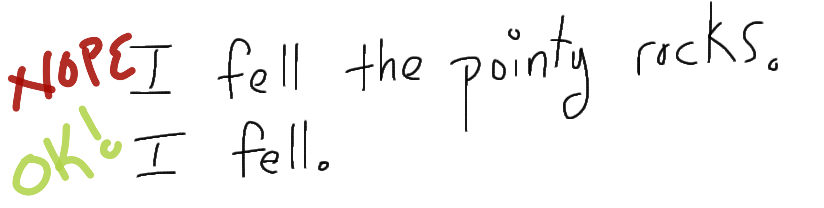

Some verbs demand more, like an object.

Other verbs absolutely forbid objects.

Other verbs absolutely forbid objects.

And other other verbs*** can go either way.

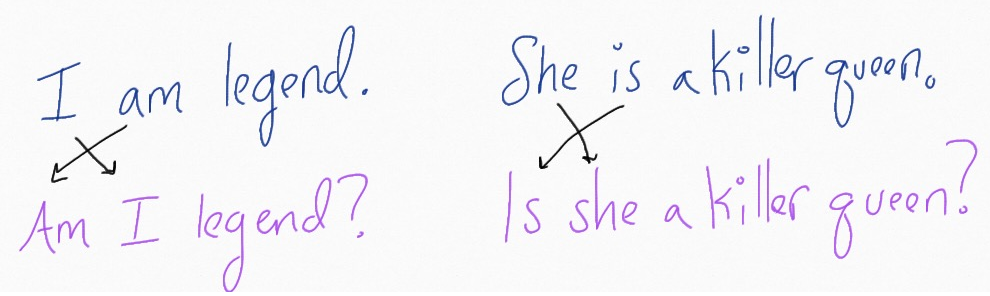

All my examples up there are declarative main clauses, the most basic type of clause. They’re just statements – I’m telling you what’s going on. But you can also have interrogative main clauses, which is a fancy way to say “questions.” Those clauses, of course, are what I use when I don’t know something and I want you to fill me in.

All my examples up there are declarative main clauses, the most basic type of clause. They’re just statements – I’m telling you what’s going on. But you can also have interrogative main clauses, which is a fancy way to say “questions.” Those clauses, of course, are what I use when I don’t know something and I want you to fill me in.

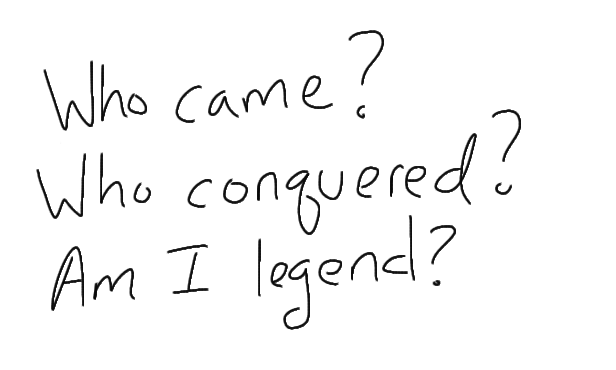

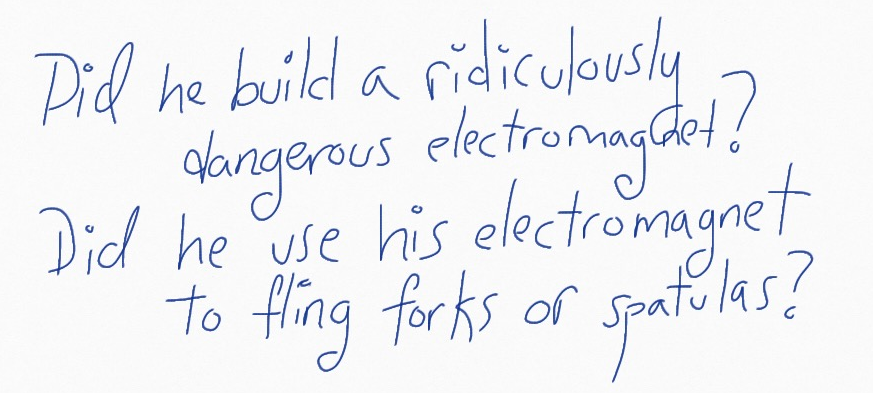

Ready for a subcategory of a subcategory? There are two kinds of interrogative clauses, open and closed. Closed interrogatories have a certain set of answers I expect you to pick from.

Ready for a subcategory of a subcategory? There are two kinds of interrogative clauses, open and closed. Closed interrogatories have a certain set of answers I expect you to pick from.

For the first question, you can choose “yes” or “no”; for the second, “forks” or “spatulas.” And sure, you could also say “man, hell if I know,” but that’s not an answer, at least not in terms of grammar – it’s breaking the question.

For the first question, you can choose “yes” or “no”; for the second, “forks” or “spatulas.” And sure, you could also say “man, hell if I know,” but that’s not an answer, at least not in terms of grammar – it’s breaking the question.

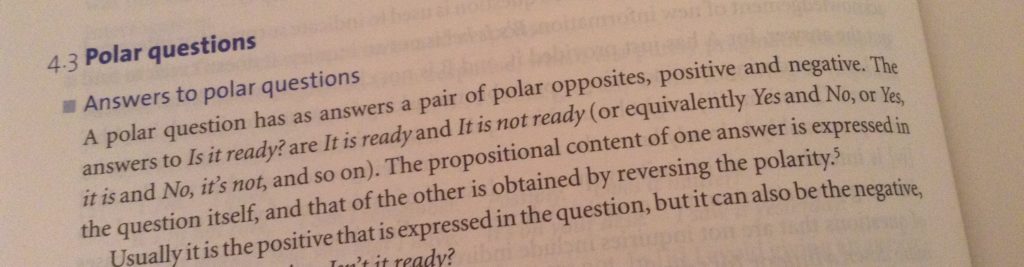

If the only answers are “yes” and “no,” it’s a polar question, thus leading to the only time I’ve ever seen “reversing the polarity” used sincerely.

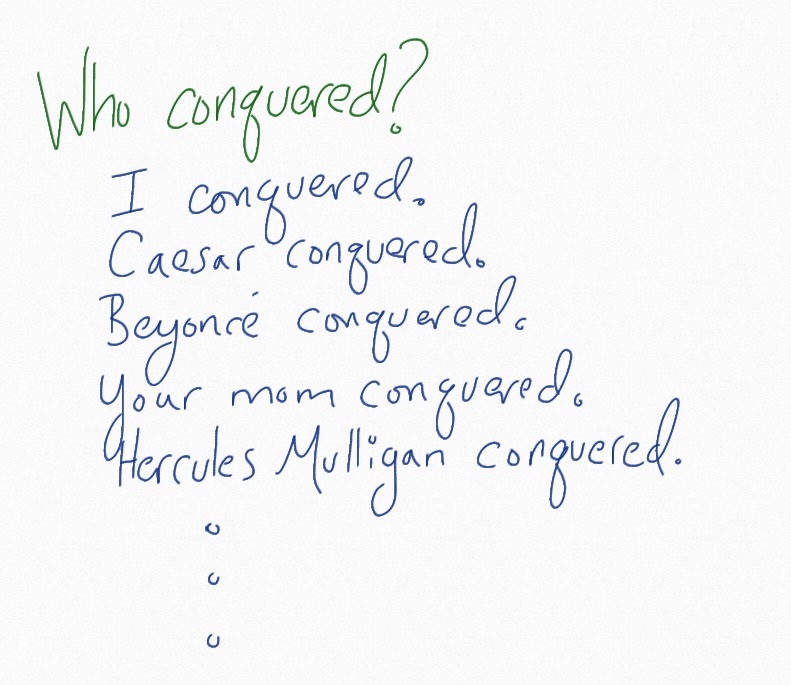

Open interrogatories are, uh, open. I’m not narrowing you down to a couple choices. You’re free(er).

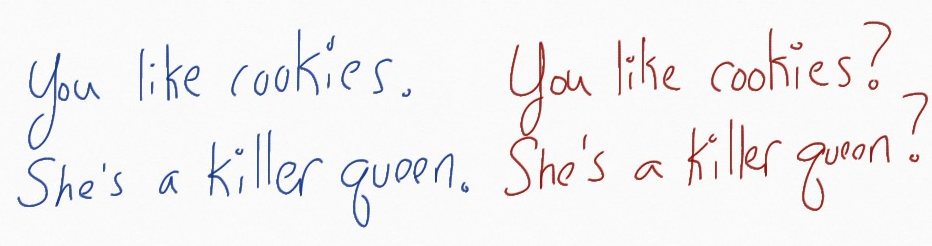

It’s not hard to tell that an open interrogative is a question, because they get a special question word – who, where, what, how, all that jazz. Closed interrogatives don’t. So they need another way of marking their question-ness, something to show that they’re not plain ol’ declaratives.

It’s not hard to tell that an open interrogative is a question, because they get a special question word – who, where, what, how, all that jazz. Closed interrogatives don’t. So they need another way of marking their question-ness, something to show that they’re not plain ol’ declaratives.

You can show the difference with only the tone of your voice, if you want. Think about how differently you’d say these pairs:

But more often than not, we show the difference in the grammar, too, with a little thing I like to call subject-auxiliary inversion.****

But more often than not, we show the difference in the grammar, too, with a little thing I like to call subject-auxiliary inversion.****

Swap Meet

Auxiliaries are a special kind of verbs. They’re the little ones you see all the time, things like “am” and “are” and “can” and “will.” You may’ve learned them as “helping verbs.” They follow slightly different rules than regular verbs (your “run” and “dance” and “extrapolate”), so if you want to make a declarative main clause with an auxiliary into a closed interrogative, it’s easy. You grab the subject, you grab the auxiliary, and you switch their places.

But what about declarative clauses without auxiliaries? There have to be, like, at least ten or twelve of those out there in the wide world, right?

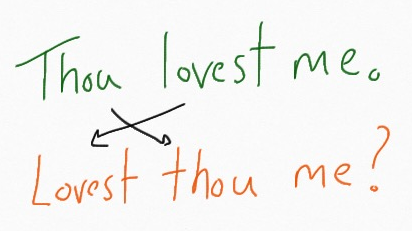

Well, if we were living back in Shakespeare times, this would not throw us off at all. We would do exactly the same thing.

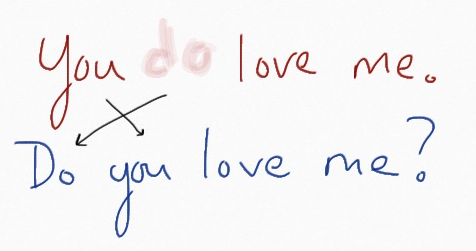

But fortunately for our teeth and life expectancies, we are living in 2016. And these days, if you want to make an auxiliary-free declarative into a closed interrogative, there’s only one thing to do: use “do.”

But fortunately for our teeth and life expectancies, we are living in 2016. And these days, if you want to make an auxiliary-free declarative into a closed interrogative, there’s only one thing to do: use “do.”

Yup, we just throw “do” into the sentence as a kind of shadow auxiliary, not with any real meaning, only there to fill out the grammar. If the declarative is “You love me,” we pretend it’s “You do love me” so we have an auxiliary to grab and switch.

And now, a confession. Remember when I said that open interrogatories are no problem because they have special question words? Like eight paragraphs ago? Well, I lied.

And now, a confession. Remember when I said that open interrogatories are no problem because they have special question words? Like eight paragraphs ago? Well, I lied.

I mean, it’s true that open interrogatories get question words, but sometimes that’s not enough. Sometimes they need subject-auxiliary inversion, too. Look, I was trying not to frighten you, ok? Be cool, y’all.

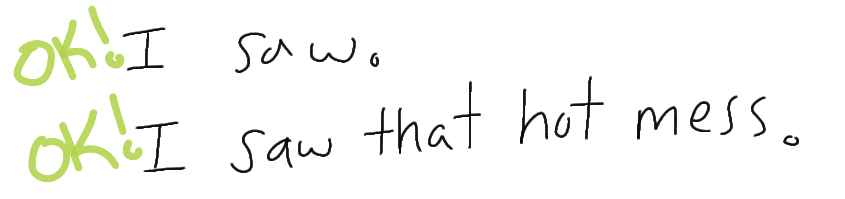

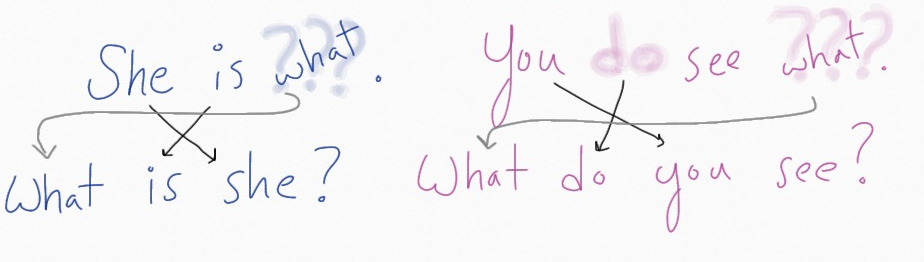

The examples I gave above are the most straightforward open interrogatives – the ones where I don’t know the subject. All I need to do is swap in a question word for the big blank space in my mind where the subject should be, and I’m done.

But what if I know the subject and want to ask you about something else?

But what if I know the subject and want to ask you about something else?

Then there are a couple of steps. First I swap in a question word, but I push that sucker up to the front of the clause. Then I roll up with that sweet sweet inversion, chucking in “do” if I need to.

Then there are a couple of steps. First I swap in a question word, but I push that sucker up to the front of the clause. Then I roll up with that sweet sweet inversion, chucking in “do” if I need to.

All right. That’s everything you need to know about interrogatives.

All right. That’s everything you need to know about interrogatives.

…as main clauses.

Subordination Nation

A subordinate clause is a clause inside another clause. The inside clause is the subordinated clause; the outside clause is the main clause.

Subordinated declarative clauses are often marked with “that” (see: six centimeters up). “That” works as a little warning: heads up! We’re subordinating over here!

Subordinated declarative clauses are often marked with “that” (see: six centimeters up). “That” works as a little warning: heads up! We’re subordinating over here!

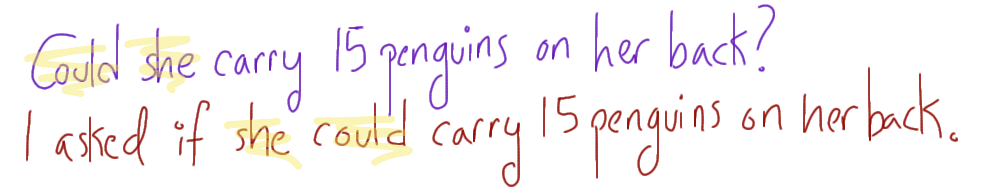

Subordinated interrogative closed clauses also get a marker – “whether” or “if.” Subordinated interrogative open clauses already have a question word, so they don’t need another marker.

At least, not another word marker. But both closed and open interrogatives do have another way of marking their subordinated-ness. Just to make it clear they’re not main clauses this time, we show the difference in the grammar, too. You see where I’m going with this? It’s a little thing called not having subject-auxiliary inversion.

Which also means there’s no need to bring in “do.”

Which also means there’s no need to bring in “do.”

Back up there in the original question, Laura ended her open interrogative subordinated finite content clause with a question mark, which is how she often sees these things end.

I wonder what the term is for this kind of question/statement?

That seems perfectly natural to me, too. And yet, here in my bigass grammar book, it’s not mentioned. There’s a little section about punctuation of embedded questions, but it says that they end with a period. That’s it.

What’s that mean? Could be a couple of things. Could be that using a question mark is much, much more informal than I thought it was. But Huddleston and Pullum are very good about marking that sort of thing with a little note about how common (or not) it is.

Could be that it’s a particularly American way to punctuate. H&P are also excellent markers of trans-Atlantic differences, but the book is, at the end of the day, decidedly British. Maybe it slipped through.

Or it could be that a final question mark has become more common in the last 14 years. The book was published in 2002, after all. Maybe that’s changed.

Dunno. Maybe I’ll put together a survey, or dig through a corpus or two, and see what I come up with.

I mention this as a reminder. Their book, and my post here, are not admonitions about what you should do. I am describing and labeling what some people do do – the mostly educated, often white, generally older, mostly middle/upper-class speakers of what’s called Standard English. Because that’s the dialect Laura wrote to ask me about, and because that’s the dialect discussed in this giant grammar book I’m holding. But every examination of grammar is a snapshot, a glance at what some group of people is doing at some brief moment in time.

So if this recipe for open interrogative subordinated finite content clauses seems weird or unnatural or way way formal to you, you probably speak a different dialect from me, and from H&P.***** Which doesn’t mean your way is wrong, or bad, or dumb.

It means we need another note in the book.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*You also sometimes see it called an “indirect question.” That’s less handy, though, because “indirect question” is also the usual term for a question that isn’t shaped like a question, like melodramatically crying out “I’d give anything to know the state of affairs!” instead of just asking “What’s happening?”

**As always, “always” means “almost always.”

*** The finite vs non-finite distinction also has to do with verbs, specifically with their tense. I’m not gonna dig into that today (this post is already hella involved) but I’ve touched on it before.

****I like to call it that because everyone else calls it that. What can I say? I’m a rebel.

*****For one, many dialects do keep subject-auxiliary inversion in subordinated clauses, as in “I wonder what is she doing?” (That difference does get a note in H&P.)

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

I got one reference this time, y’all, and it’s a beauty. You know it, you love it, it’s The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language by Rodney Huddleston and Geoffrey Pullum. Specifically chapters 4, 10, 11, and 20.

I took that picture of my cat a few weeks ago, when I first got the book (and she immediately sat on it). She died last Monday, after a solid eighteen years of perching wherever the hell she wanted.

Rest in peace, little kitty. It’s easier to read now, but it sure is lonely.

Oh I’m so sorry about your cat; she looked really friendly! As for this post, I’ve always wished that in English we could just put the interrogative word wherever we wanted. For example, we could say “he went to the what to get milk?” I feel that would make it easy to ask questions about arguments in verbs that use multiple arguments. A lot of other languages seem to allow this