so i read somewhere on the internet that all languages are spoken at the same rate. meaning that even if a language has lots of extra words or really long words, people tend to say them faster so that their sentences take about the same length of time to say as a language with short or fewer words. this seemed like complete poppycock to me, since people from the south (in america) seem to speak slower than people from the north, even though in theory we all speak the same language. do you have any idea if this is true or not?

(sorry for such a long question)

-syntrell

***

Dear Syntrell,

Is it true? Well, sort of. Within certain parameters. Or at least it’s a working hypothesis.

I know my equivocation is less exciting than reports on this topic elsewhere on the internet, like this article from Time:

“[This study] answers one of the longest-standing questions about human speech. […] at the end of, say, a minute of speech, all of the languages would have conveyed more or less identical amounts of information. […] they will tell you the same story in the same span of time.” –”Slow Down! Why Some Languages Sound So Fast,” Time Magazine

But this is because, apparently unlike the crack Time science reporting squad, I have actually read the study in question, “A cross-language perspective on speech information rate,” by Pellegrino, Coupé, and Marsico:

“However, these strategies [of the different languages] do not necessarily lead to a constant information rate.” – the freaking abstract of the study, goddammit Time

Time’s article sounds like it’s summarizing the secondary hypothesis of the study: the idea that languages get across the same information in the same amount of time. Or, using the classier sciencey phrasing of the study, languages have “equal overall communicative capacity.” This makes sense, if you think about it. Languages get spoken by humans (last I checked) and humans have the same basic communication needs and restrictions the world over. PC&M spell out the upper and lower limits of our rate of info-per-minute: if we speak too quickly, our message is unintelligible to our listeners. If we speak too slowly, our information becomes so inefficient that it’s useless (if there were a language that took ten minutes to get across the information that we fit in the phrase “look out behind you,” then that language would be less than helpful).

So a constant info-per-minute rate seems reasonable, intuitively. But how would you prove or disprove whether all languages communicated information at exactly the same rate? How on Earth are you going to precisely, scientifically quantify this? Seriously, take a minute and think about how you’d design this study. Go for it. Ruminate. I’m in no hurry.

Right off the bat, there are problems. Here’s one: how are you going to get samples of speech? More specifically, whose speech are you going to get? And when? What’s the context? We want an example of nice, normal rate of speech, so we have something to compare, but to do that we’re going to have to define something as “normal.” Different people speak at different speeds, and even the same person’s speed will vary. I might start speaking quickly if I’m explaining the backstory of an anecdote to the one person in the group who doesn’t know it already, or I might slow down to tell you that you! Shall not! PASS!! (And there, the act of slowing down itself conveys extra information – that I really really mean it. How do you control for that?) Social context affects speech rate, and unfortunately for scientists, language use is always social.

Here’s another problem with natural speech: how can we get people in different languages talking about exactly the same thing? Anybody who’s been to a PTA meeting knows that some sentences are more informative than others. If we want to compare information communication in different languages, we should have everybody trying to communicate the same info, but most sentences people say are unique. We could have microphones set up for weeks before we got exactly matching sentences out of folks.

PC&M deal with both of these issues by having their subjects read short stories aloud. This allows for precision in their measurements, but the trade-off, of course, is that now the language they’re measuring isn’t natural. The results they get are still meaningful, but having to constrain the language the speakers use makes their applicability to regular speech more questionable. It’s like those physics problems that ask you to ignore friction or gravity or the sun or whatever, so you can take a stab at the theory. Though in linguistics it’s not generally recommended to test your experiment in a vacuum.*

Ok, we’ve dealt with the little problems. Let’s really get our teeth into this. To find info-per-minute, we need to divide the sentences into chunks – then we can work from there to get info-per-chunk and chunk-per-minute. So what chunks should we use?

You went with “words,” didn’t you? Not words.

Words are a pain because they vary so much between languages, and it’s not always easy to decide where a word ends or begins. It might look easy on a page, with those nice little spaces on either side, but it ain’t. Is “chat room” two words? What about “chat-room”? “Chatroom”? Has the meaning changed? Really, “what counts as a word” is a dense enough topic for some other post. And it only gets worse in Japanese.

Nope, for PC&M it made more sense to divide the sentences into syllables. Much easier to cut up all the languages into discrete bits that way.** And with the recordings in hand, they could put together the syllable-per-minute rate pretty easily. Which leaves one question: how did they find out how much information is in each syllable?

They didn’t.

Hot damn, this is the stickiest part of the whole business, and I am hella impressed by how cleverly they sidestepped the difficulties. See, information is a hard thing to quantify. If it were easy, this post would’ve been about eight words long. One way of trying to define it is to make a big list of all the possible jobs a syllable can do – mark case, show definiteness, show number, dozens more – and give each syllable a score based on how many jobs it does. (This is apparently what Time thinks PC&M did.*** Damn it, Time.) But this assumes that we know all the possible jobs of a syllable, and how much weight to give to each one. Is it more informative to be a content word than to show that a verb is in the second person? How much more? 10%? 200%? It’s iffy. PC&M worked with this concept, too, in a later study, but in the one we’re looking at, they avoided this difficulty entirely with the power of math.

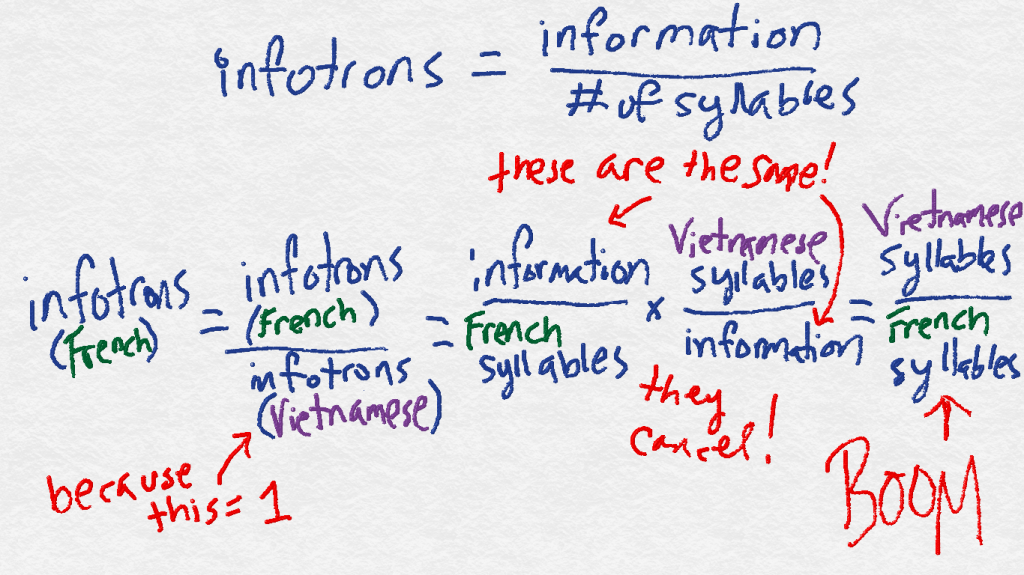

For this study, see, they didn’t need the exact amount of information in each syllable. It didn’t matter if one syllable was doing seven jobs and another was doing two. All they needed was the average amount of information per syllable in each language. So they picked one language (Vietnamese) to be the baseline: syllables in Vietnamese had an information score of 1. PC&M said that information was unitless, which seems to me like a tragic lost opportunity, so I’ll say that a Vietnamese syllable contains one infotron of information.

With that baseline set, PC&M could just compare the other languages to Vietnamese, skipping the “divine all that a syllable contains” step entirely. Because all the languages had the same total information, they divided the number of syllables in the Vietnamese text by the number of syllables in another text, say French, to get the average French information per syllable, 0.74 infotrons. Pretty slick.

And you thought the last post had a lot of math.

So! Good googly moogly, after all that, what were the results??? Here you go:

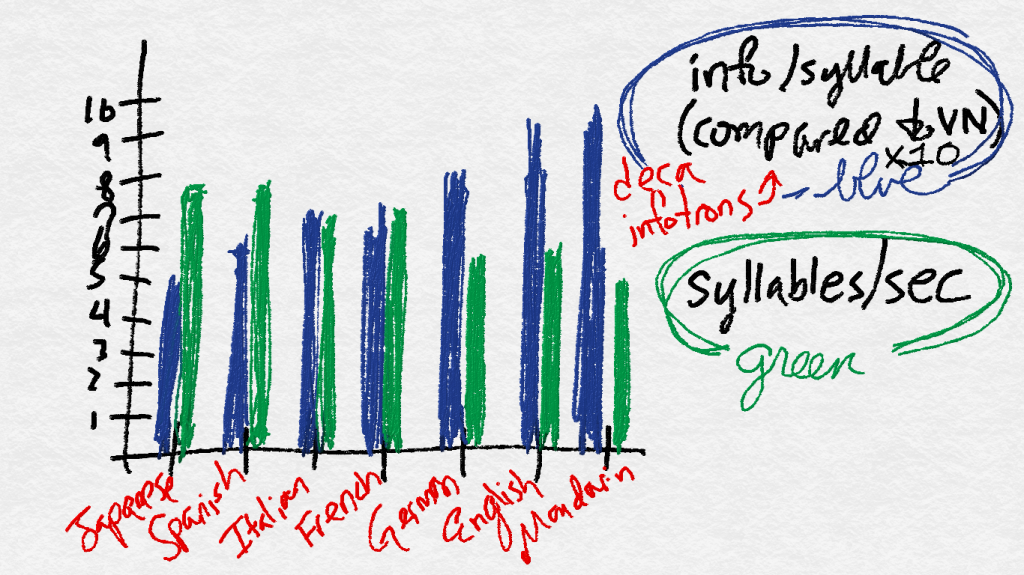

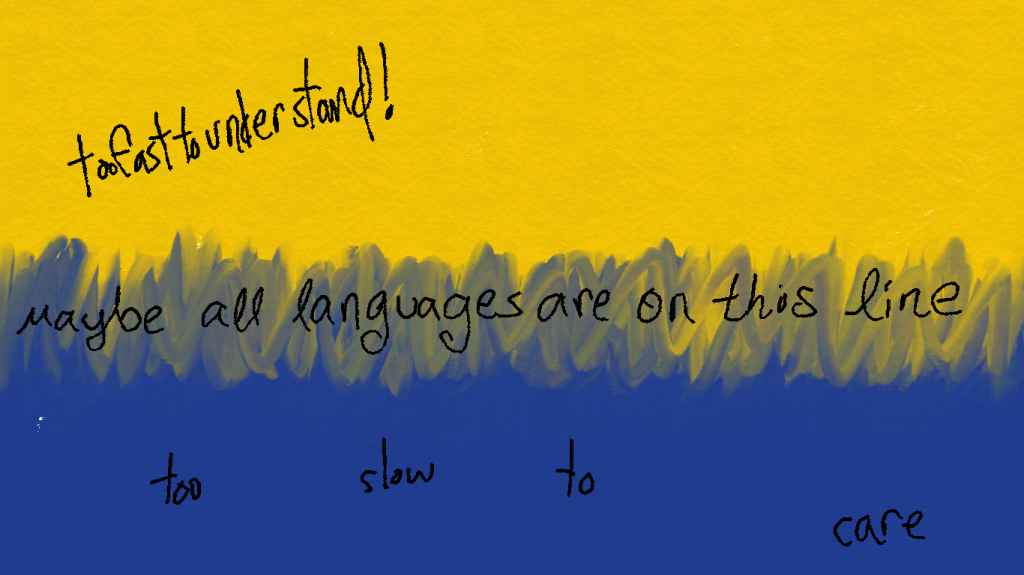

This is taken directly from PC&M’s graph in the study. My rendition is more, uh, approximate. And colorful!

Check out that sweet correlation! Japanese has less information per syllable, and Japanese speakers went through the texts more quickly. Mandarin Chinese has a ton of information in each syllable, and Mandarin speakers talked more slowly. Kickass! That’s what we’d expect, if the info rate is constant!

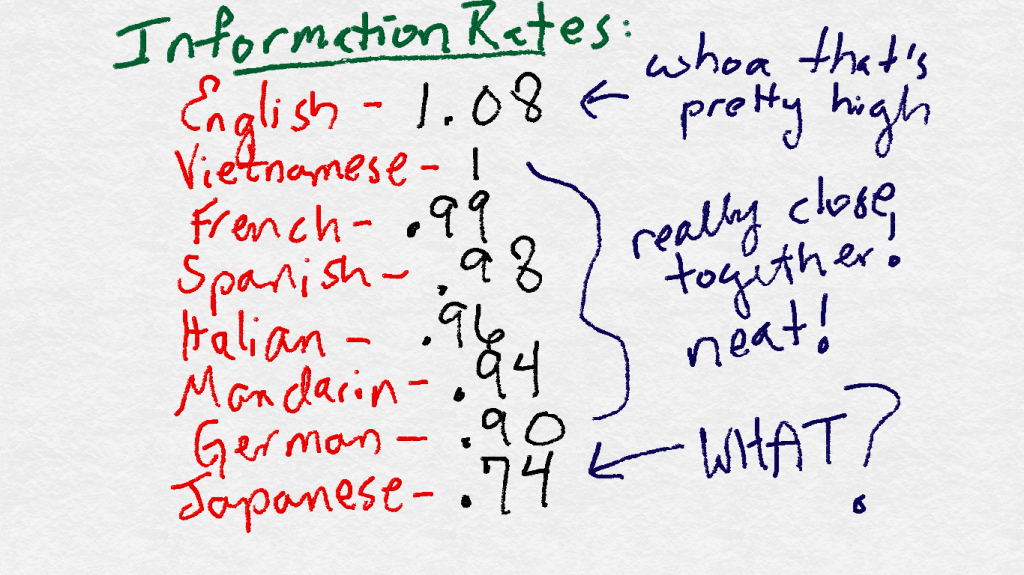

All we have to do now to see if the rate of info-per-second is the same across languages is simply compare how long it took the speakers to get through the texts. Since the information is the same, if the times are all the same, then the information rate is constant. Here, too, PC&M compared their 7 languages to Vietnamese with the value of 1.

Wait a minute. WAIT JUST A MINUTE.

So what are the actual, put-it-in-the-headlines results here? Kinda the opposite of what Time went with. They definitely show a strong negative correlation between infotrons and speech rate, but their findings for Japanese, especially, suggest that maybe there isn’t one exact information rate. Maybe there’s a range of info-rates between that upper and lower limit. As PC&M put it, “Our hypothesis of equal IR [information rate] across languages is thus invalidated[.]”

You designed your own study back at the beginning, right? If, after all these questions and considerations, you think it’s up to snuff, I’d like to direct you to the LSA’s page for linguistics grants.

Does this mean that the whole concept is going to be tossed out like last week’s asparagus? Probably not. Equal communicative capacity is a big, messy hypothesis, and the only way to find support for it (or to disprove it) is for many different researchers to take bites out of it from all sides, like sharks attacking a giant peach. Pellegrino, Coupé, and Marisco made certain decisions in crafting their study; other researchers will make other choices, and if studies from several different angles show similar results, well, we’ll be getting somewhere.

But “A cross-language perspective on speech information rate” was not the end-all be-all of the field that Time implied it was. It did not prove the hypothesis forever and ever and ever. In fact, it showed doubts about the theory. Though I suppose if Time had gone with that angle the headline would’ve been “Scientists Prove Japanese Surprisingly Uninformative.” The most obvious proof that this study didn’t “answer[] one of the longest-standing questions about human speech” is that Pellegrino, Coupé, and Marisco, with the addition of Oh, have been conducting a larger, better version of this study – more languages, more speakers, more ways of analyzing the results. Preliminary results are out now, and the new paper should be available soon! I’m gonna get the gang together and go to the midnight premiere!

Ok, maybe not. I would, though. I can’t wait to see the next stage in this complicated, unresolved, murky, and fascinating area of linguistics.

But forgive me – there was another part to your question, an aspect I haven’t addressed yet. That was so many words ago that I think I need to repeat it:

“this seemed like complete poppycock to me, since people from the south (in america) seem to speak slower than people from the north, even though in theory we all speak the same language.”

This looks like you just threw it in as a little example. Maybe as a side-note. A wee pointer.

But it is not.

It is a whole other thing, it implies a whole other question: is the Southern accent actually slower than other varieties of English?

And it, too, is hella complicated.*****

See you in two weeks.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

(sorry for such a long answer)

(not really)

*I know what you’re asking yourself: if having the information be the same is so important, then why’d Pellegrino & friends decide on short stories? Why not really simple single sentences? (Alright, maybe you weren’t, but it’s what I was asking myself while I was reading, so here we are.) Well, turns out PC&M considered this, but simple sentences are dangerous in translation. Because they are short, word choice affects the length more seriously. A single word that’s particularly long or short in one language can make a disproportionate impact. With short stories, this problem’s gone, but now there’s a danger of difference in style or in nuance of information. (PC&M used 20 different stories and took the averages, to minimize this.) So here, too, we have a trade-off: every option is useful in some ways, problematic in others. In science as in life.

**Though generally Japanese is split not into syllables but into morae, and the use of an odd division there is probably one of the reasons that they went in for a much bigger study after this one. You’ll see when we get to the results.

*** “The investigators next counted all of the syllables in each of the recordings and further analyzed how much meaning was packed into each of those syllables. A single-syllable word like bliss, for example, is rich with meaning — signifying not ordinary happiness but a particularly serene and rapturous kind. The single-syllable word to is less information-dense. And a single syllable like the short i sound, as in the word jubilee, has no independent meaning at all.” God DAMN it, Time, where are you even getting this from? In the more recent study they did, long after the Time article came out, OPC&M made an enormous list of possible grammatical information a syllable can contain that’s kinda relevant to this. But nowhere do they get into semantics. And in this study, the one that Time‘s talking about, they took the average info-per-syllable, and didn’t analyze individual syllables at all.

****Not completely arbitrary – PC&M chose Vietnamese because it’s an isolating language. But there’s no mathematical reason that Vietnamese should be 1 and not, say, Xhosa.

*****Update: You know, I said that, but now that I’ve finished the southern speech post, this one is way tougher.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

Not a huge variety among the references today — there’s the study, “A cross-language perspective on speech information rate,” by Pellegrino, Coup*, and Marsico. Then the preliminary results of their upcoming study in the same vein, wherein Oh has joined them, and the powerpoint of Oh’s presentation of same.

If you think I’m being too hard on Time, well, I don’t. They’re not any worse than most of the science reporting out there, but that’s an indictment of science reporting generally, not a compliment for them. On the other hand, at least Time’s willing to print ballsy opinion pieces. (Sierra Mannie was almost a linguistics major, y’all! I am all kinds of upset that she went with classics instead.)

If you’d like to hear more linguists grousing about crappy language reporting in popular media, the folks at Language Log have cataloged some excellent (terrible) examples.

Now I’m left to philosophize: is bad linguistics reporting better than none at all?

When I was an ad agency copywriter, one of our clients was a Mexican beer. i wrote scripts that were recorded in both Spanish and English and the Spanish versions were always longer.

Interesting! The scripts were longer or the recordings were longer? Or both?

[…] The Running of the Syllables […]

I’ve studied Japanese and lived there for a few years. In general, a Japanese sentence can have waaaaay less info than an English one.

Say you come late into a room where all your co-workers are chatting. Good luck trying to figure out what they are talking about because by that point in the conversation, the actual topic will probably not be spoken again.

Some examples.

In English I might say, “The dogs are running.” Five syllables. And you know it’s more than one dog, so that’s added meaning -without- an added syllable. That s at the end doesn’t change the syllable count.

In Japanese, the sentence would be “dog run.” They don’t have articles like “a” and “the” (which again ads to major translation issues, but can’t get into that here). And they don’t have plurals. To impart the information that there is only one dog, or more than one, they would have to add words like “one dog runs,” “many dogs run” or the exact number if they know it “seven dogs run”. AND YET, the Japanese sentence “dog run” has at MINIMUM -six- syllables. More depending on how you conjugate the verb (polite form, simple form, honorific form, etc).

Another example.

A perfectly acceptable Japanese sentence doesn’t have to have a subject. So someone could easily say “taberu” to you. Three syllables. What does this mean in English? Well, it could mean “I eat.” “He/she eats.” “They eat.” “You eat.” In English, we get -more- information across (who is eating) with -fewer- syllables. Two.

So basically, no wonder studying this is so crazy difficult. It’s fascinating, but I’m happy to let someone else do all the work and just read the results.

Plus, the form also is a kind of information — whether it’s in honorific or simple form tells you something about the relative status of the people speaking. Is that “as much” information as the number of dogs? Hard to quantify. Hence the decision in this study to skip assigning relative information scores to individual syllables altogether.