Dear Language Nerd,

I see “Latin@” all the time on tumblr (referring to people from South America/Central America/Mexico). What’s the deal with the “at” sign?

-Gringo (Gring@?)

***

Dear G,

Grammatical gender and a healthy dose of language politics. Let’s dig in.

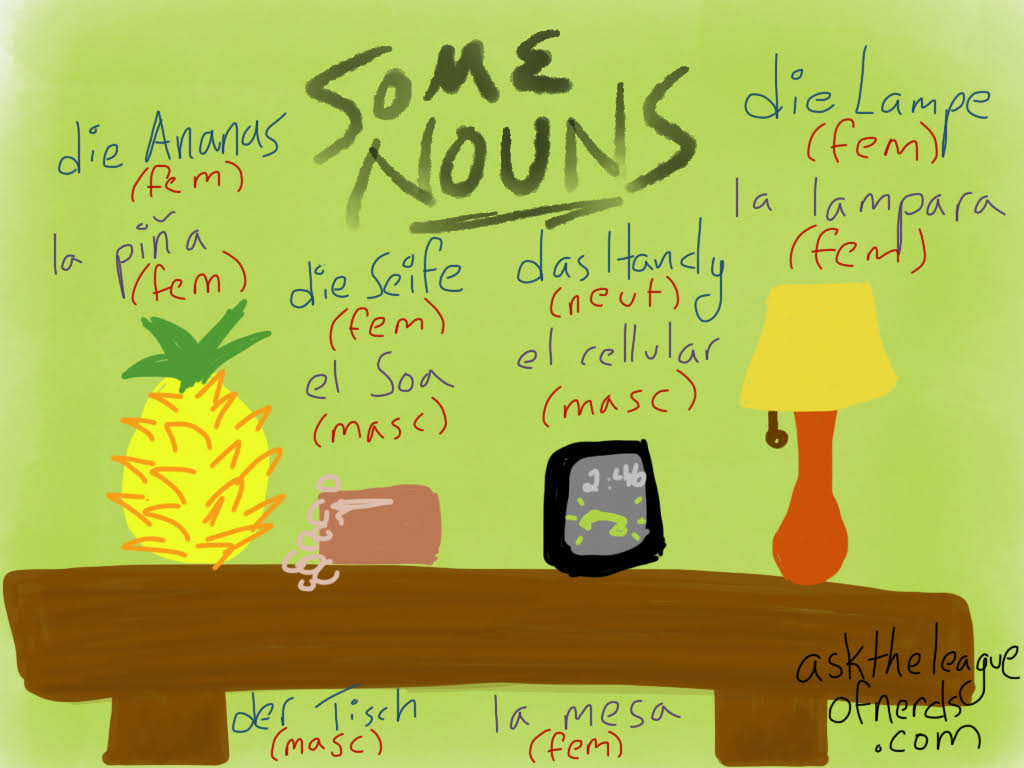

We have a handful of nouns in English that are connected to a specific gender. “Mother” is a noun for females. So is “queen.” “Father” and “king” are for males. If you don’t feel like specifying, you can go with “parent” or “monarch.” We’ll get into a few more examples later, but gendered nouns in English are the exception, not the rule – “phone” and “pineapple” and “soap” and “lamp” don’t have grammatical gender.

Other languages, though, take this concept way further. Gender isn’t just connected to people or creatures that have a biological sex; it’s pervasive, part of the grammar system. It’s a gender free-for-all. Gender for everybody! Gender for everything!

People and other living critters are mostly in the category you’d guess, like la abuela for “the grandmother” and der Mann for “the man.” But anything inanimate is a crapshoot.

Spanish has masculine and feminine categories; German adds a third, neutral group. Other languages might have these genders, none, or even more, but we’ll stick with these two high-school staples as examples. When a language has gender as part of the grammar, it affects more than just the nouns. Articles, adjectives, sometimes even verbs will change to match.

Spanish has a straightforward pattern for marking gender. There’s la as “the” for feminine nouns and el for masculine. Most feminine nouns end with -a, most masculine nouns with -o. And the adjectives match: they get an -a on the end if they’re describing a feminine noun, and an -o for masculine. So we have la caculadora redonda (“the round calculator,” feminine) and el nabo reflexivo (“the thoughtful turnip,” masculine). As usual, there are exceptions, and also as usual, I’m skipping ‘em.

German is less well-organized. For “the,” feminine nouns take die (pronounced “dee”), masculine take der, and neutral take das.* And if you say “the,” then any related adjective just gets an -e on the end. If there’s no “the” to bear the brunt of the gender information, the adjectives get gender endings, feminine -e, masculine -er, and neutral -es. So far so good? Well, hang on. There’s no simple -a/-o distinction for telling the genders of German nouns apart. Here’s a brave soul attempting a list of possible endings, including -ich, -ling, and -us for masculine, -enz, -schaft, and -ung for feminine, -a, -il, and -ment for neutral… and 42 more. Jeez.

All this is grammar – just patterns in language, apolitical and amoral. But language is always connected to the people that use it, and that means the patterns take on meanings beyond antiseptic rules and lines.

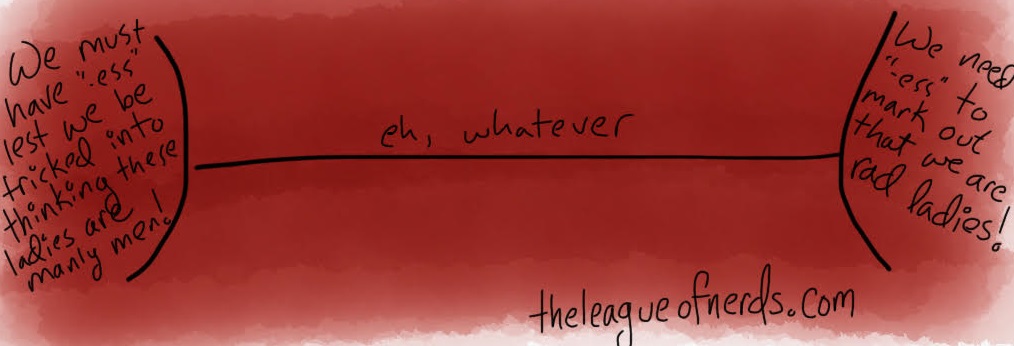

Let’s come back to English for a second, because it’s simpler,** and look at how our patterns are influenced by our culture and attitudes. We’ve gone through phases of more and fewer feminine markers, especially on job names. “Actress” is pretty ingrained now as the distaff counterpart to “actor,” but most of our other old “-esses” have dissipated. When’s the last time you heard about a “songstress” or a “doctoress”? It seems weird, like it’s somehow really urgent to know that this doctor is a woman. Might be good info for an ob/gyn, but as a rule we don’t need it. And since we use “doctor” as the normal form, the unpleasant implication of “doctoress” is that a female doctor is a strange beast.

There tends to be a range of ideas about these kinds of markers. Right now, the vast middle of English speakers thinks it’s not usually necessary to mark out the gender of a job. But there are exceptions. On the one hand, you have the honest-to-God opinion of ye olde misogynists that we need to mark out the womenfolk trying to do a man’s work so that we may avoid them. On the other hand, you occasionally see groups of women marking themselves with “-ess” as a kind of group identity. I’m thinking particularly of fanfiction.net, a writing website dominated by young women, where it’s not unusual to see self-identification as an “authoress.”

I have sympathy for the authoresses, because I find that when you go by neutral titles like “linguist” and “nerd” people have a disconcerting habit of referring to you as “he.”

But we can drop these endings easily when we feel like it. If our culture changes such that more women are in charge of meetings or schools, we can switch “chairman” and “headmaster” to “chairwoman” and “headmistress,” or we can just as easily create the neutral titles “chair” and “head.” No matter which you choose, it doesn’t affect the other words in the sentence. Our biggest problem is indefinite “he-or-she,” which I covered here (the answer is “they,” y’all).

This is mild peskiness at worst, but as women gain more power and recognition in Spanish-speaking cultures, it’s more difficult to reflect that with gender-neutral language because grammatical gender is more pervasive. One workaround that writers can go with is combining -o and -a into one symbol – the @ sign. So Latin@ is a way of writing Latino and Latina together, instead of having to write out both. And this works for other words as well, including adjectives, though you still have to use a slash for el/la.

It’s not necessary to do this for turnips, but it’s good for professional titles and other people-words. El/la maestr@ “the teacher,” el/la chic@ “the child,” that kind of thing. And yeah, el/la gring@, I suppose.

Gender-neutral German is even tougher, but you didn’t ask about that, now did ya?

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*It gets complicated because “the” changes for case, too. 3 genders x 4 cases = 12 singular definite articles. But some of them are the same spelling, doing different jobs. Anyway, if you’re learning German, don’t get hung up on this – skip ahead to fun stuff and come back to “the” when you’ve got your footing.

**For once.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/askthleagueofnerds

The @ sign is only one way of mixing Spanish endings, by the way. You also see Latina/o and the like, and sometimes Latinx. The last one is for writers rejecting the masculine/feminine divide, a social stance you might well see on tumblr, so keep an eye out for that.

References! Gender in German here and here, gender in Spanish here and here. And here’s a couple lovely podcasts about English and gendered nouns from Lexicon Valley. And if you’re looking further afield, the Wiks article on gender neutrality covers several more languages.

I’m headed to Ethiopia next week! Oh man, I am so excited. I hear that the internet cuts out some, though, so please bear with me if posts don’t come through on time.

There’s also a growing movement of people who prefer “Latinx” because they feel “Latin@” reinforces the gender binary.

Mentioned that in the refererences/notes.