Dear Language Nerd,

Not to brag or anything, but I have totally mastered writing in English. I don’t mean the nuances of grammar or the subtlety of poetry or any of that pishposh. I mean the physical act of writing. I put down the letters, others decode the sounds, and frankly it’s beautiful. Grown men cry. Children faint. And I’m ready to take my skills to new arenas. What other ways of writing are out there, besides the English alphabet?

***

Wow, it’s an honor to be an advisor on this adventure, o anonymous monarch of penmanship. Kinda wish I could’ve gotten this question handwritten instead of typed, but them’s the breaks. Let’s jump right in.

If you just want to dip your toes, you could start with non-English alphabets. An alphabet, to be clear, is a writing system where the symbols (letters) correspond one-to-one with the language’s phonemes. I’ve written about phonemes at ridiculous length before, but I’ll refresh: a phoneme is the smallest meaningful unit of sound in a language. In English, /b/ is a phoneme. You can’t get smaller – half a /b/ isn’t useful. When we talk about phonemes we stick them in slashes, //, to remind us that the sound is not always the spelling; to talk about what’s written, we use pointy brackets, <>.

English isn’t a perfect alphabet.[1] If it was, we wouldn’t need special brackets to differentiate sound and spelling – they’d always be the same. But that ain’t so. Sometimes one phoneme can be written two ways: <kick> and <cat> both start with /k/. Sometimes it’s the opposite, and <c> can be /k/ in <cake> but /s/ in <science>. Sometimes a single phoneme needs two letters, like <sh> for /ʃ/.[2] When you poke your nose into other alphabets, you can see how close they came to phonemic perfection. Turkish gets a little closer by giving /ʃ/ its own unique symbol, <ş>, while German goes and throws another letter in there, <sch>.

But this, while interesting, is no challenge for the likes of you. How about an alphabet with completely different letters? I mean, there’s no compelling reason to write the /m/ phoneme as two little hill buddies. Why not make it a square instead?

If that sounds promising, check out Korean. It sure looks different, but it is in fact an alphabet. What’s more, in Korean there really are reasons for the shapes representing different phonemes. /m/ gets <ㅁ> to represent a stylized closed mouth, because by gum, that’s where we say /m/. And /b/ is written <ㅂ> — the same mouth-square, but now there’s air coming out. It’s genius, and because it’s so logical, you can pick it up in an afternoon.

But enough, enough with the alphabets! We need sound-symbol correspondence that isn’t based on phonemes, dammit! Well, fine. There are three other ways to map sound to writing: abugidas,[3] abjads, and syllabaries.

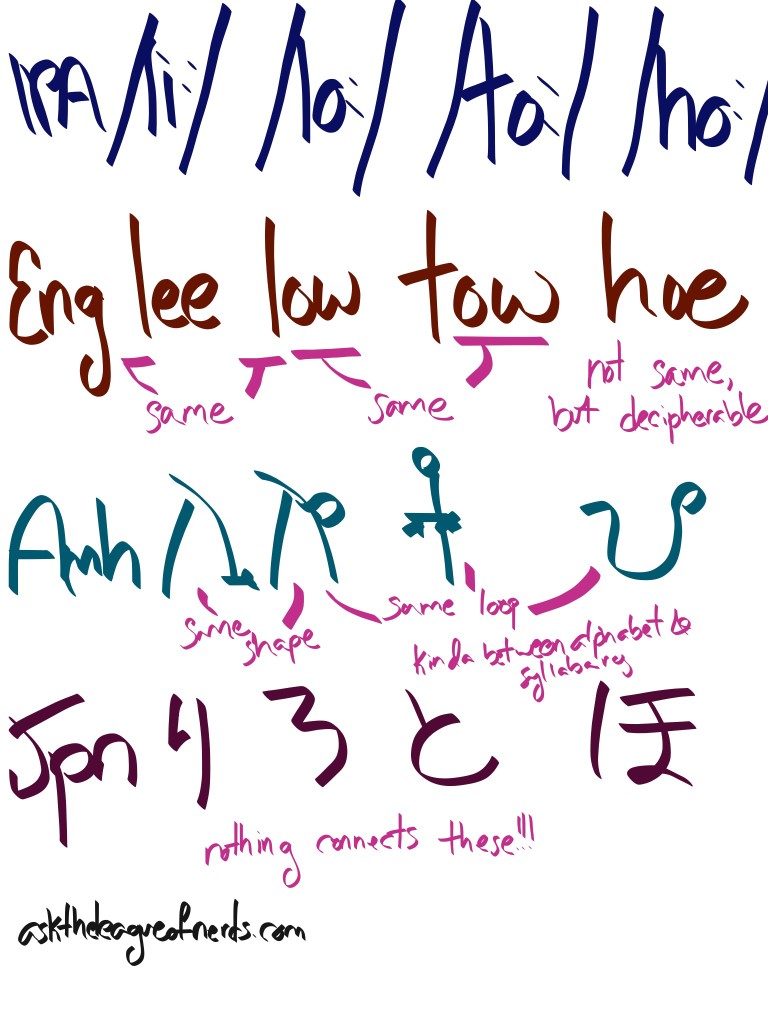

An abugida is like an alphabet that decided that vowels are way, waaaaaay overrated. Consonants are much cooler, and get their own symbol, which the vowel just modifies a little. Which is plenty, alright? Don’t coddle your vowels. Like so:

These four symbols are from the Ge’ez abugida script, used to write many of Ethiopia’s friggin EIGHTY-TWO languages. Man, I gotta get over there.

And if Amharic ain’t enough, there’s also a slew of gorgeous abugidas across southern Asia (check them out, they are kickass and swirly).

Now abjads figure that even abugidas give vowels too much credit, and kick them out entirely. Yup, in an abjad all you write is consonants. The two big-name abjads are Arabic and Hebrew.

Syllabaries are something else again. Like the name suggests, these guys are based on syllables. The simplest syllable is a lone vowel phoneme (“a” is a syllable in English). Bigger, heftier syllables are made by adding consonants to either side of the vowel. You could use a delicate hand, just add one up front, consonant-vowel, CV: “so,” “he,” “key,” “wha?” Or you could go nuts, CCCVCCC: “strengths.”[4]

The most famous syllabary is Japanese, which accepts only genteel CV syllables.[5] Wait, isn’t that the same as an abugida – a consonant and a vowel in one symbol? Well, yeah, but they’re different. In syllabaries, there is no interest in the phonemes that make up the syllables. Each syllable is an island unto itself.

Once I learn some Amharic, I will come back and edit this to be less embarrassingly ugly.

Still not enough, you say? You’ve harnessed the hangeul, considered the kana, delved into Devanagari, in short mastered every method the human race has yet produced for setting out our sounds on paper – and still you are not satisfied? Still you demand more?

FINE.

FORGET sounds. Chuck ‘em out the door. Mail ‘em to Peru. Defenestrate the little beasts, I don’t care. Out, damn phonemes! Begone!

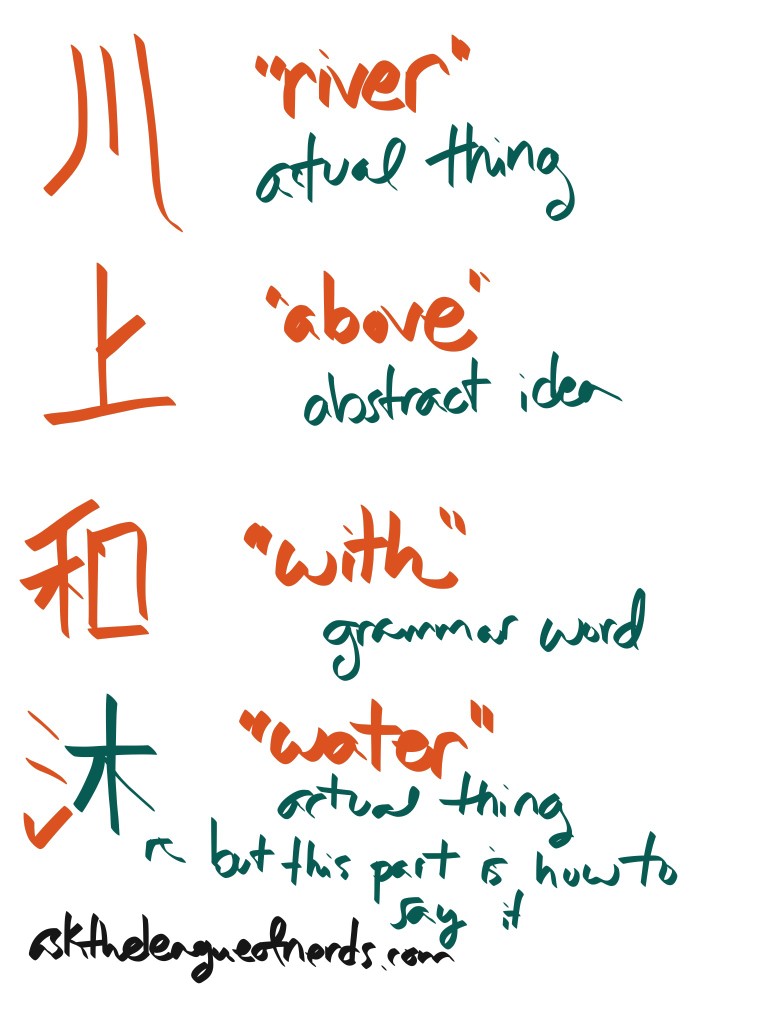

We’ll talk logograms. And that means we’re talking Chinese. In a logographic script, a symbols stands for a unit of meaning, not a unit of sound.[6] Some are pictograms, which started out as regular doodles of regular stuff a few thousand years ago, though they are now so simplified and stylized it can be hard to recognize them. Some are symbols of abstract concepts, like “up.” Some are symbols of grammar, like “with.” And some are symbols of, ah, um…

…somearesymbolsofpronunciationokayfine.

Many of the pronunciation-guide symbols are so old that they’re not really relevant anymore, and the pronunciation section is just one small part of the bigger logogram. Logograms in general are about expressing a word. But man, I just can’t get away from phonology. Not even for a paragraph. Jeez.

Better go refenestrate the buggers.

Know what else uses logograms? Japanese! I know, I was just using Japanese as an example of a totally different thing! But Japanese has three different scripts – two syllabaries and a set of logograms, derived from Chinese, which get mixed and matched for different purposes. The syllabaries have 46 basic symbols each; the logogram set is around 2,000. So there. Learn to write Japanese. That’ll keep you busy for a while.

And if you still want more, you’re just gonna have to invent a writing system yourself.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

[1] Really, no writing system is a 100% “perfect” example of its type. There’s always bits and pieces poking out, which I’ll be glossing over in order to get the ideas across without a thousand qualifications. AS IS MY WAY.

[2] And sometimes we do a couple of these at the same time, just to screw with language learners (please see <th>).

[3] The word “abugida” comes from the first 4 letters in the Ge’ez script, just like how “alphabet” comes from the old opening “alpha, beta.” Similar thing with “abjad.” “Syllabary,” not so much. Also, spellcheck recognizes “abjad” but not “abugida”? That is some really specific knowledge you have and then lack, spellcheck.

[4] If you’re thinking that’s not enough C’s, remember we’re talking phonemes. And <ng> is two letters, but only one phoneme, /ŋ/. Similar with <th>.

[5] Well, morae. GLOSSING, PEOPLE.

[6] I’m avoiding the word “morpheme.” Y’know, sometimes I think “aw man where am I gonna get a new post idea for the next forever,” but then I remember that I haven’t even MENTIONED morphology on this site yet. Linguistics is BIG.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

I wrote this with no references! In fact, I wrote it specifically because I could do it with no references, since Istanbul is in the middle of a friggin nation-wide blackout. I hope you appreciate that I went trucking all over town to find wifi and get this post to you.

Anyway, what with the wifi, I did go checkin’ up on my facts. Sadly, I know neither Chinese nor Amharic, and used charts from Wiks and omniglot.com, respectively, as references for my beautiful artwork. And here’s another, more serious breakdown of these writing systems, if that’s a thing you want.

Great article as usual! That was interesting to note the difference between abugidas and syllabaries, because there are some syllabaries with logical relations between syllables (or morae, if you prefer) of the same class, such as eskayan (http://www.omniglot.com/writing/eskayan.htm). But I guess its kinda subjective. Also, I liked how you referenced the kit on zompist; I found that when you try making these yourself, the fundamental questions you encounter help you realize why certain writing systems are the way they are (i never understood why the D had a vertical line, when it adds no additional distinction from a C, until i thought about how people sometimes read upside down). But really, great post!

Yeah, the LCK is great for getting you to recognize your unconscious assumptions about language. Hmm, hadn’t heard of Eskayan before — I’ll check it out!

I’d be glad to hear what you think of it!

[…] mentioned Amharic’s Ge’ez script before in my post on writing systems, here. Abuguidas […]