Hi! I’m a Spanish/French major and I like to write in my spare time. My latest story is about a band of vigilante murderers and for the past few weeks I’ve been trying to make up a noun that the vigilante characters use to label people as ‘someone that deserves to die/be killed’. I’ve played with English words of different dialects as well as looked up Greek and Latin words, but nothing sounds right. I’ve also tried taking the Spanish and French verbs for ‘deserve’ (merecer/mériter) and blending them with the verb ‘to die’ (morir/mourir), as well as translating the phrase into Latin phrase (qui meretur occid). I’m stuck and would like your help! Thanks!

Candi

***

Dear Candi,

Sounds like you’re missing an “-er.” To show you what I mean, we need to get a handle on morphology. And to do that, obviously, I need to talk about the Power Rangers.

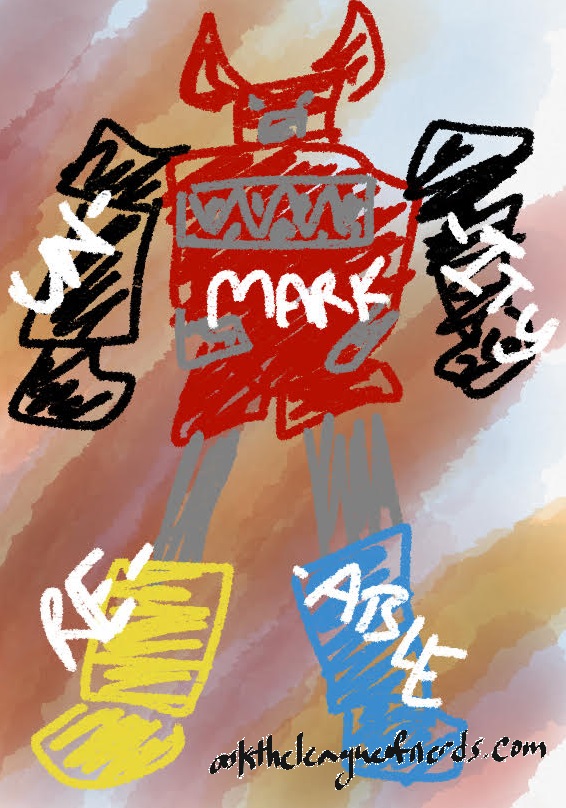

Specifically, about the Zords. You may recall that in basically every episode, the evil Rita Repulsa would send some human-sized monster to Earth for whatever nefarious reason, the Rangers would whoop up on it, and then Rita would magically make it about twenty stories tall. At this point, the Rangers would call in their Zords, individual mechas that joined up into one giant mecha Megazord for further monster-stompage.

Like… every episode. It was not a complicated show. Also not afraid to reuse footage.

The Red Ranger was the leader, and his Zord formed the core when they linked up.* So in this totally reasonable analogy, he’s our root.

The root of a word is the part that carries most of the meaning. Plenty of words are only roots, the Red Ranger alone. Like “cat,” or “purple,” or “shenanigan.” In morphology, we’re only thinking about meanings, not the length of the word or how many syllables it has. These are single words with single meanings – single roots.

The remaining Zords are our prefixes and suffixes. They also have only one meaning, but they don’t come alone – they have to be attached to the root. The plural marker “-s” is one example. You can’t just go around saying “ssssss” and expecting people to understand you, but you throw it on the end of “shenanigan” and now we know there’s more than one, “shenanigans,” enough shenanigans for the whole evening probably.

That’s a suffix, stuck on the end of a root. A prefix, as you may have guessed, goes on the front end. You can “like” a picture on fb, and then when you scroll by it again you can “unlike” it. Here “un-” is your prefix, meaning “not.” Those are the two main ways we add on to our roots in English. Other languages sometimes have circumfixes, where one meaning goes on both sides of the root,** or infixes, which go in the middle. But English doesn’t do circumfixes. And infixes? Abso-fucking-lutely, but only the one.

The nice thing about these guys is that we can stack ‘em up. We can put two prefixes on the front, then the root, then two more suffixes if we feel like it. Like so –

All of these, every Zord – prefix, root, suffix, or otherwise – is called a morpheme. Hence “morphology.”

Coming back to the question, I think you need an “-er.” That is, the suffix that turns “write” into “writer” or “camp” into “camper.” A morpheme that indicates a person. See, you’re writing this as a phrase, even when you translate it into Latin as “he deserves death.” Try it as “death-deserver” and you might be able to find something snappier.

As always, best of luck.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*Except in unusual cases like the Dragonzord Battle Mode, but work with me here.

**Like German, where one way of making past tense is to put both “ge-” at the front of a verb and “-t” at the end. “Lernen” becomes “gelernt,” “machen” becomes “gemacht.” Y’know.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

Morphology info from my handy old textbook Language Files. Power Rangers info from vague childhood memories, supplemented by a recent, totally research-focused Amazon Prime binge.

Honestly, I was never a huge Power Rangers fan. Way more into Animorphs. But despite the equally obvious post title, the Animorphs are unfortunately not a great analogy for morphemes. Code-switching, maybe. Or semantics? Hmm.

I love the quirky examples you use ^^

Thanks :D

Latin and Greek often use participle future active/passive in that sense. The famous ‘morituri’ in Latin means ‘Those who are about to die’ but is used in the sense ‘Those sentenced to death/those whose destiny it is to die’. If you want a non-periphrastic form for something like ‘Those whose destiny it is to be killed’, you would need to resort to the Future Passive Participle in Greek.

[…] define grammar with grammar – to look at what jobs this category of words can do in a sentence, what endings they can take on, and what they require or abjure¹ in the sentence around […]