Hey Language Nerd,

I’ve been seeing a commercial lately for a toenail-fungus remover called, in all seriousness, “Jublia.” WTF? “Jublia”?? How do medicines get these ridiculous names?

JRN

***

Dear JRN,

I’m guessing they went with “Jublia” in hopes that their customers would make the cognitive leap to “jubilant” and “jubilee.” Because nothing brings out the joy in me like toe fungus. Either that or they’re big into fishing and want you to know?

Fish don’t even HAVE toes, tho. (Public domain photo. Also, whoa, I didn’t realize that Jubilees are only a Mobile, Alabama thing until I went hunting for this picture. Sorry for you, rest of the world.)

Whenever someone makes a new anything, be it a company or a car or an app or whatever, they want a name that’s distinctive, memorable, and creates particular connotations or images in the minds of potential customers. The Ford Expedition is supposed to make you think about having an adventure. The Dodge Charger sounds fast and aggressive. And Tesla naturally brings up that maverick genius, while the Tesla Model S is a throwback to Ford’s Model T – both ways of emphasizing that their cars are meant to change the whole industry.

But medicines get extra-weird names, because they have a whole extra set of naming rules to deal with courtesy of the United States Food & Drug Administration. See, in the 90s, about 7,000 people died each year because they got the wrong medicine. Li’l Courtney was supposed to get Blahblahmerex, say, but somewhere between when she went to the checkup and when she took the pill, a nurse or a tech or a pharmacist or a doctor misheard or misread the directions, and she ended up with Blahblahverox instead. The FDA didn’t give numbers on other problems, but if there were seven thousand straight-up deaths, there were probably plenty of other people who didn’t heal as well or as quickly as they could have because they were taking the wrong meds. The stakes are higher than with most of the stuff on the market – if you get two cars mixed up and buy the wrong one, you can take it back. If you get two medicines mixed up, you might not have that chance.

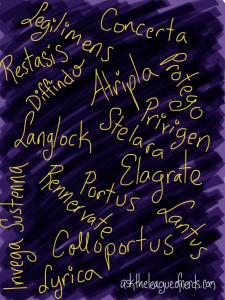

Half of these are from RxList. The other half are from Hogwarts. Good luck.

Which is why the FDA jumped in. Their main goal is to lower the chance of mistakes by making sure that the names of new medicines coming out are different in sound and spelling from any names already out there. Name-makers go further and further into pseudo-Latin to make sure their brand names are different enough, and new drugs sound more and more like spells from Harry Potter.

And, as a secondary goal, the FDA rules against names that are utter bullshit. Like “Leg-Reattaching Ointment.” Or “Dr. Mike’s Inexplicable Cure for Everything.” Heck, the example they use in the guide is “Best” – can’t be throwing that into names unless there’s some serious evidence of actual best-ness.

There are other odds and ends. Drug names can’t look like medical abbreviations, either. Docs write “QID,” for example, to mean “four times a day,”* so that’s out as a naming option. And there are some rules that overlap between the two goals: you can’t name your product for an ingredient that’s in your mix but doesn’t have an effect, because either it’s not on purpose (which could be confusing) or it is on purpose (and you’re trying to get attention for something that doesn’t matter, which is bullshit).

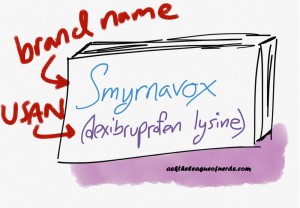

And then there’s USAN stems. No brand name for a medicine can look like or sound like any part of an USAN, which is the other, sciencier-looking name that comes after the brand name. USAN stands for United States Approved Name, and you sometimes also see International Nonproprietary Name (INN). These are the generic names for drugs, and they have their own, even more complicated naming process, because they have to give specific information about what the drug is. Every anticoagulant ends in “-arol,” every endothelin receptor antagonist ends in “-entan,” and so on through lots of other things I don’t understand, list here. They’re also supposed to be useful around the world, so no “th” allowed in USANs, for one, because “th” is too weird.

In theory the USAN folks could do their thing, and the brand-name makers do theirs, and they could both stay out of each other’s way. The USAN website, though, makes it clear that there are assholes out there in pharmaceutical-land trying to piggyback their names on the importance of the USANs, sneaking the official stems into their brand name. And then the USAN makers, who take their differentiation more seriously, have to take the high road and come up with a whole new stem for that kind of drug. “The USAN Council adheres to the principle… that ‘in no event… shall the Secretary establish an official name so as to infringe a valid trademark.’ It is incumbent upon the manufacturer to likewise refrain from infringing on official drug nomenclature stems for use in trademarks,” they write. Unwritten, but implied: “YOU DICKS.”

The FDA doesn’t just list all these rules and hope they work out, either. They run two huge tests on every drug name before it hits the shelves: Name Simulation Studies (NSS) and Phonetic & Orthographic Computer Analysis (POCA). POCA is pretty much running the proposed name through a big name database and looking for matches. You can actually download the software yourself, if you’re planning on marketing a new pharmaceutical anytime soon: here.

The Name Simulation Studies are more intense. For those, the FDA gets actual nurses and pharmacists and whatnot together and makes them act out using the proposed name like they would in their regular work, to see if anyone gets confused. And when I say “their regular work,” I mean every single friggin aspect. Every task the name could be used in – “prescribing, transcribing, dispensing, administering.” And every variation of those tasks. The name written on lined paper. Written on unlined paper. Typed into a computer. Spoken over the phone. Spoken in a noisy office. Shouted at a nurse running down the hall while the patient is going into cardiac arrest in the ER. Whispered into the void. Everything. And with different people each time, so they don’t get used to the name between tasks. Their guide has a breakdown of an NSS with seventy different people in twenty-three different situations, all for one fairly uncomplicated drug.

So next time you see an ad for Brilinta or Lipitor or what-have-you, remember — they go a long, long way to get to these ridiculous names.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*It’s an abbreviation for the Latin quater in die, and I can see why they abbreviate it, since no one wants to catch a glimpse of “die” on their prescription.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

Well, after a few posts in a row that were one book apiece, I’ve got a ton of references for you this time. Here is the FDA’s guidelines, a powerpoint guide that’s easier to follow, and an even easier summary from a law blog – whatever suits your temperament and free time levels. Here is USAN’s web page – they have a very thorough FAQ, it’s good – and the list of USAN stems. List of medical abbreviations here, and “QID” in particular here. You can download POCA here. Drug names for the pic from RxList, and spell names for the pic from, uh, growing up as a millennial. I linked to Wait But Why before when I wrote about robots, but they wrote about Tesla cars once too, and it was great, check it out. And finally, a fascinating New York Times article by Neal Gabler about naming a new technology, whose mention of the FDA set me on the right track for this post.

I actually watched a video about this once in a marketing class. so on top of all the fda stuff apparently there are firms who’s entire purpose is to name medicine. they had a random word generator they would use plus lots of focus groups. apparently they occasionally rename diseases too. this video claimed erectile dysfunction was a marketing term and not an actual disease when Viagra came out but I haven’t found any valid sources about that. anyways cool post!

Viagra came out in 1998, but the term “erectile dysfunction” has been used since the early 70s, so seems unlikely. But there are absolutely companies entirely focused on naming! The NYT article at the end of the references is all about that side of naming & goes into some of the companies and their processes.