oh my god language nerd i am learning turkish and it feels like everything is backwards!!!! AM I CRAZY WHYYYYYYYYYYY???

-alimi

***

Dear Alimi,

You are not crazy, o emphatic person. You are totally correct. Don’t flip, it’ll be okay.

Sentences are made of words. Mind-blowing, I know. But the words don’t come in any ol random order. They come in chunks. Think about this sentence for a sec:

The penguin with a broken heart ate a herring on toast.

Don’t think about the meaning, heart-wrenching though it is. Think about the chunks of information. You could break this into just two chunks:

The penguin with a broken heart / ate a herring on toast.

Or you could go for more:

The penguin /with a broken heart / ate / a herring on toast.

But you wouldn’t break it like this:

X The / penguin with a / broken / heart ate a / herring on / toast.

That would be weird.

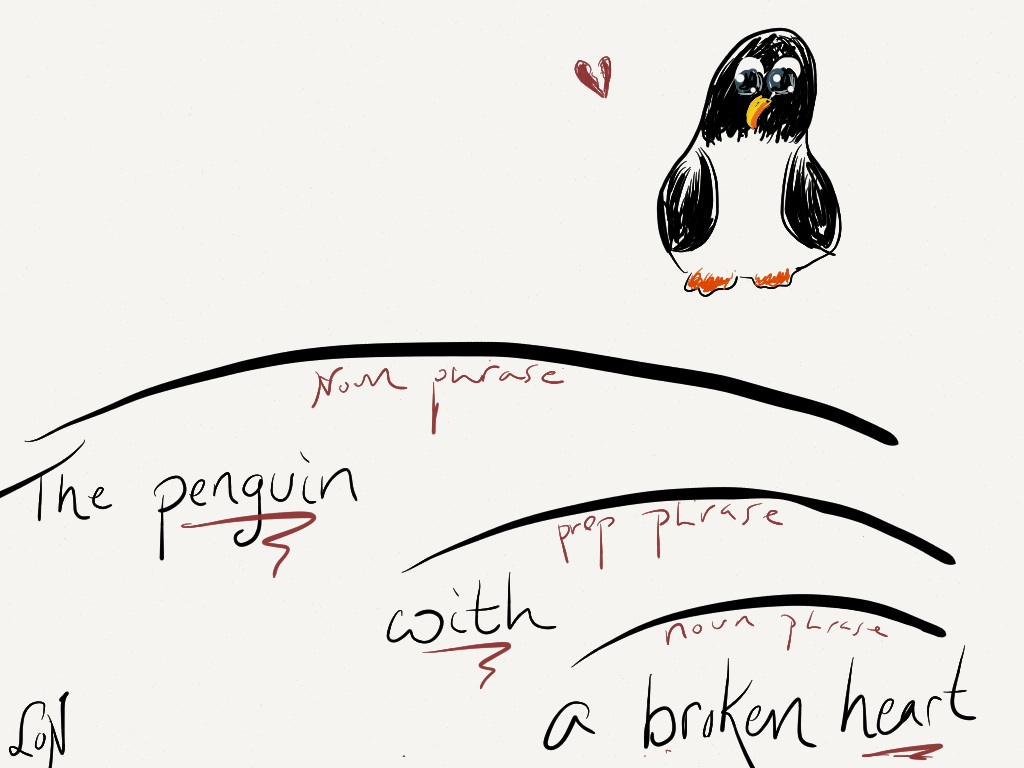

The little chunks that make up the sentence are called phrases. And each phrase has a word that’s in charge. In “a herring on toast,” that word is “herring.”* The other three words revolve around that herring. In “the penguin with a broken heart,” it’s “penguin.” Since these are nouns, the phrases they’re in charge of are called noun phrases.

So far, not too tough, hmm? That’s because the heads here are the most meaningful words, too. But heads aren’t about meaning – they’re about grammatical power. But let’s look at the smaller phrase “with a broken heart.” This is a little funky – the heart is what’s important to the meaning, but “with” is the word that’s organizing the other words. The head is “with,” and it’s a prepositional phrase. “A broken heart” is a yet-smaller phrase inside that phrase.

Let’s draw this out:

So in two of our three phrases here, the head is in the front. And this is what’s usually true in English. In “ate a herring on toast,” the head is “ate.” Or if we talk about the desperate, lonely journey the penguin began the next day, the phrase “to the ends of the earth” is headed by “to.” Our heads come first. Hence, we call English a head-initial language.

But there’s another option for languages. They can be head-final.

No prizes for guessing which one Turkish is.

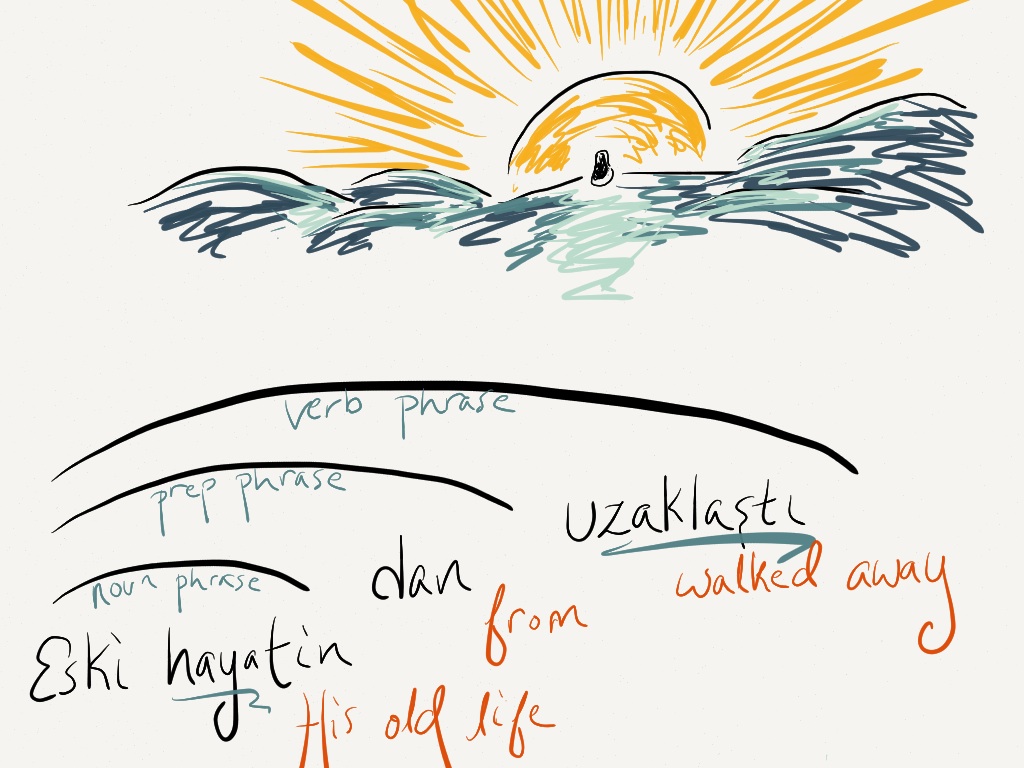

In regular writing, you put the “-dan” right up on the word before it, no spaces. “Hayatından.” Just fyi.

In Turkish, prepositions come after the nouns they refer to – so really, they’re postpositions. Verbs come after their objects. Nouns come after relative clauses. Everything.

Which makes it easier, in some ways. Words aren’t splashed about willy-nilly, hither and yon. It’s not like there’s one rule for adjectives and a different one for nouns. There’s one pattern – the opposite of what you’re used to, but just one pattern. What’s more, it’s a pattern your brain can recognize and learn to deal with. Listen, practice, and give it time.

Really, Turkish is more regular than English. In “a broken heart,” the head is the noun “heart,” but it comes after the adjective. In eski hayat “old life,” the adjective still comes before the head noun, but it makes more sense because heads are supposed to be last in Turkish. Some head-initial languages take their duties seriously, like Spanish, but we English-speakers always gotta have our exceptions.

And, bonus: once you get Turkish down, you’ll have a head start (heh) on any other head-final languages you want to pick up. So if your next stop is Tokyo, you’re good to go.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*Skipping determiners entirely today. Life’s tough.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

One reference today – went back to Andrew Carnie’s Syntax: A Generative Introduction.

Like running into an old friend in a cafe.

In Paris.

In the spring.

With a penguin.