Everybody knows that a noun’s a person, place, or thing. But in a sentence like “That the man was overwhelmed was obvious,” is “man” the subject? Or is the whole phrase “that the man was obvious” one big noun?

MLP

***

Dear Mulp,

You are mixing two things here: subjects and nouns. Noun is a category of word, the category that “man” falls into. Subject is a function, a job in a sentence. It’s a job that nouns often do, but they’re not the only thing that can fill that slot.

In “The man ran away” or “the elephant was obvious,” the subjects are nouns – “man” and “elephant” respectively. But in your sentence, the job of subject is done by a clause, which is basically a mini-sentence inside a larger sentence. “The man was overwhelmed” is a sentence (the subject is “man”). Then we take that whole sentence and use it as the subject for a bigger, more complicated sentence, with “that” on the front to help the reader know what’s going on. “That the man was overwhelmed” is the subject, but it’s a clause, not a noun.

With that out of the way, let’s take on an even more important point: “a person, place, or thing” is a crappy definition for the category of nouns.

Not that you’re crazy for thinking that; lots of people do. We don’t learn much grammar in schools, and what we do learn is wrong, or at least unfinished. “A person, place, or thing” is fine as a starting point, and it’s acceptable where it’s first learned, around second grade. Second-grade teachers mostly teach lies anyway. I’m not knocking that; we gotta start somewhere. We get the seven-year-old’s simplified-to-the-point-of-inaccuracy versions of all our subjects, so that later teachers can come back and build on them.

No, no. I’m knocking those later educators instead. Because somehow grammar never gets revisited. People leave college with no better understanding of what nouns are then they had when they were seven.

| Subject | In Second Grade | But Actually… |

| Math | Subtraction is when you start with a big number and take away a smaller number. | Negative numbers are, like, a thing.* |

| History | Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves with the Emancipation Proclamation. | Abraham Lincoln didn’t free jack diddly with the Emancipation Proclamation. |

| Science | The Earth is round like a soccer ball. | The Earth is an oblate spheroid, like a soccer ball your brother is sitting on. |

| Grammar | A noun is a person, place, or thing. | THAT’S FINE NO WORRIES NOTHING TO SEE HERE MOVE ALONG |

I got an issue with that bottom-right corner. We never revisit nouns! Or verbs! Or anything! We never even learn what grammar is, or where its rules come from. Instead of getting a more detailed, meaningful understanding of grammar in high school, we just learn increasingly esoteric grammar rules, occasionally accurate but often concocted of fluff and prejudice. I’ve groused about that in the past, so I won’t repeat myself, but we memorize these rules, more and evermore rules, as if grammar was a series of mystic proclamations from on high.

It isn’t.

Grammar is a science.

As Rodney Huddleston and Geoffrey Pullum put it, “Grammar rules must ultimately be based on facts about how people speak and write. If they don’t have that basis, they have no basis at all.” It’s like physics or astronomy. We see what’s out there, we discover, we make connections, we experiment, we make theories that fit the facts as best we can.

And, as in other sciences, people argue, find conflicting evidence, have opposing theories that they’re heavily invested in, and spend a lot of time trying to prove other people wrong. Again, though, they do it with facts about regular speech: “…when there is a conflict between a proposed rule of grammar and the stable usage of millions of experienced speakers who say what they mean and mean what they say, it’s got to be the proposed rule that’s wrong, not the usage.”

There are people in every science who believe what they want to be true, regardless of evidence or logic. The frustrating thing is that while, say, Flat-Earthers are a fairly small portion of the geology community, their grammar counterparts are everywhere. Grammarians with healthy respect for the scientific method are outnumbered by grammarians yelling that if you sail too far, you’ll fall off the edge. They’re certainly the louder voice in selecting schoolwork.

Grammar in schools is so confused and out of date that you (and many, many other students) are trying to work out what nouns are based on the wrong thing entirely. The whole schema is off. Your definition of nouns is based on the meanings that nouns sometimes have; it’s a whole lot easier to figure out grammar is by looking at – wait for it – grammar.

Thinking about what nouns usually mean can give us a starting point. Lots of nouns, and especially the most basic, normal nouns, are indeed people and places and things. But what about “entertainment”? That’s a noun, but not really a thing. What about “fear”? What about “discussion”? We can say that nouns are people and places and things and emotions and events and concepts and… it’s gonna be a long list, and at the end our ideas will still be fuzzy.

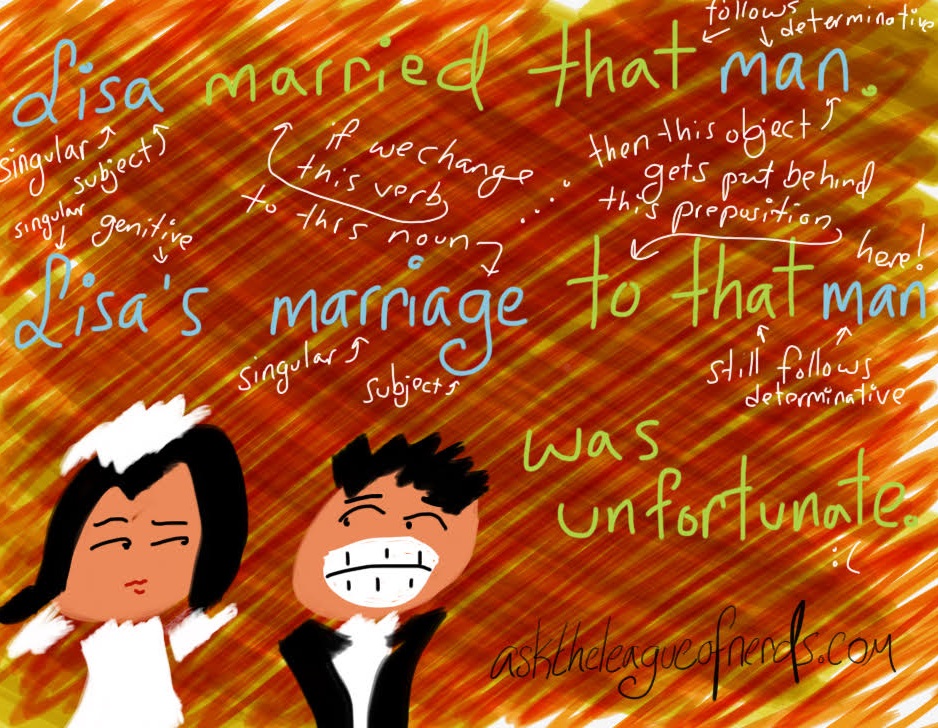

But if we think about grammar, there are much clearer distinctions. We can categorize words, and define those categories, by what happens to them and what they do in a sentence. Nouns have a singular and a plural form. Nouns have genitive forms (the ’s that shows possession). Nouns usually take one of four jobs in a sentence: the subject of a verb, the object of a verb, the predicate complement (don’t worry about that one right now) or the preposition’s complement (you probably learned that as “object of a preposition”). Nouns are often headed off by determinatives, words like “a” and “the.” Nouns never take objects; only verbs do that. But if a verb has an object, and you turn that verb into a noun, the object will become a prepositional phrase that’s still tightly connected to the noun.

Not every noun fits all of these all the time. “Sheep,” for one, doesn’t look any different as a plural: one sheep, six hundred sheep. But no other category of word ever has a singular and plural form; verbs don’t, adjectives don’t, prepositions don’t. And you can add these guidlines together. If you come across a word in a sentence that’s singular, and has “a” in front of it, and is acting as the subject, then hot damn, it’s gonna be a noun.

These are the best rules we have, and again, people came up with them by looking at a huge pile of language and seeing what nouns did. If you go looking through the Corpus of Contemporary American English (remember corpora?) and notice some totally different thing that nouns do and other words don’t, then for the love of biscuits, write up your new rule and publish it and blow everyone’s minds and they’ll rewrite their grammar books. Or at least argue with you. Because like all sciences, grammar is mutable and open to new discoveries.

It’s frustrating. Grammar as an endless series of inane “gotcha” rules to memorize is boring. Grammar as a science is mad interesting.

Look, I’ll prove it. Next post – we’ll look at the eight categories of words, what we learned in school, and what’s really out there to be discovered. It’ll be amazing. You’ll love it.

And if you don’t… um, I’ll be sad, I suppose.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*I remember being deeply suspicious when my teachers told me I couldn’t divide by zero, because I recalled being told by previous teachers that I couldn’t subtract a larger number from a smaller one, and see how true that turned out to be.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

Sadly, my reference this time is not Huddleston and Pullum’s magnificent nearly-2,000-page opus The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, because I can’t afford the damn thing. Instead it’s their smaller A Student’s Introduction to English Grammar, also excellent, a sixth the size and a fifteenth the cost. Now I have two weeks before the next post to see if my local library can get ahold of the real treasure.

Pullum also writes little snippets about misunderstood grammar odds and ends at Lingua Franca, if you want something more bite-sized. Here’s one about pronouns and another about subjects.

Y’all, this is about the eighth post I’ve done that’s ended up being largely a paean to Geoffrey Pullum.

Dear Dr. Pullum,

You are super rad.

Thank you for being you.

Love,

The Language Nerd