Dear language nerd,

The other day, my cousin asked me if I had drunk the last cup of coffee, and if I had made more. Being the incredibly important and popular person I am, I replied yes to the first and no to the second. I’m way too cool for that task. She then responded by stating that she really meant “go make more coffee.” So what’s the deal? Am I missing something? Do questions not mean anything anymore? Or does my cousin need psychiatric help?

Sincerely, a concerned citizen

***

Dear Citizen,

Your cousin does not need help. In fact, she’s engaging in quality pragmatics, specifically by way of an indirect speech act.

A speech act is when words are an action, all by themselves. Which might sound silly, but frequently words just describe an action. Saying “I drive to the store” or “I build a pillow fort” or “I create life” doesn’t cause groceries or a pillow fort or Frankenstein* to appear. You gotta back those words up by doing the deed.

But if I say “I promise to bring peace in our time” or “I threaten to knock your block off” or “I pronounce you man and wife,” then – through the words alone – something has happened. I have created a promise, a threat, and a marriage, without any physical action required at all. It’ll take action for me to fulfill the promise, sure, but I can make a promise just by saying so.

These examples are direct speech acts. There’s a particular word – “promise,” “threaten,” and “pronounce” – that directly marks what speech act you’re performing. But we don’t use these words constantly in normal speech. “I will bring peace in our time” and “I’ll knock your block off” are still a promise and a threat, respectively.

And we can go a step further, using words and sentences that have the shape of one kind of speech act in order to mean a totally different speech act. “I promise to knock your block off” is shaped like a promise, even takes its special word, but we all know it’s a threat. These are indirect speech acts, and we use them constantly.

Which is where your cousin’s totally reasonable question comes in. “Did you make more coffee?” is shaped like a question, but it’s really a request: “Make more coffee [if you didn’t already, which you should’ve since you drank it all, you bum].”

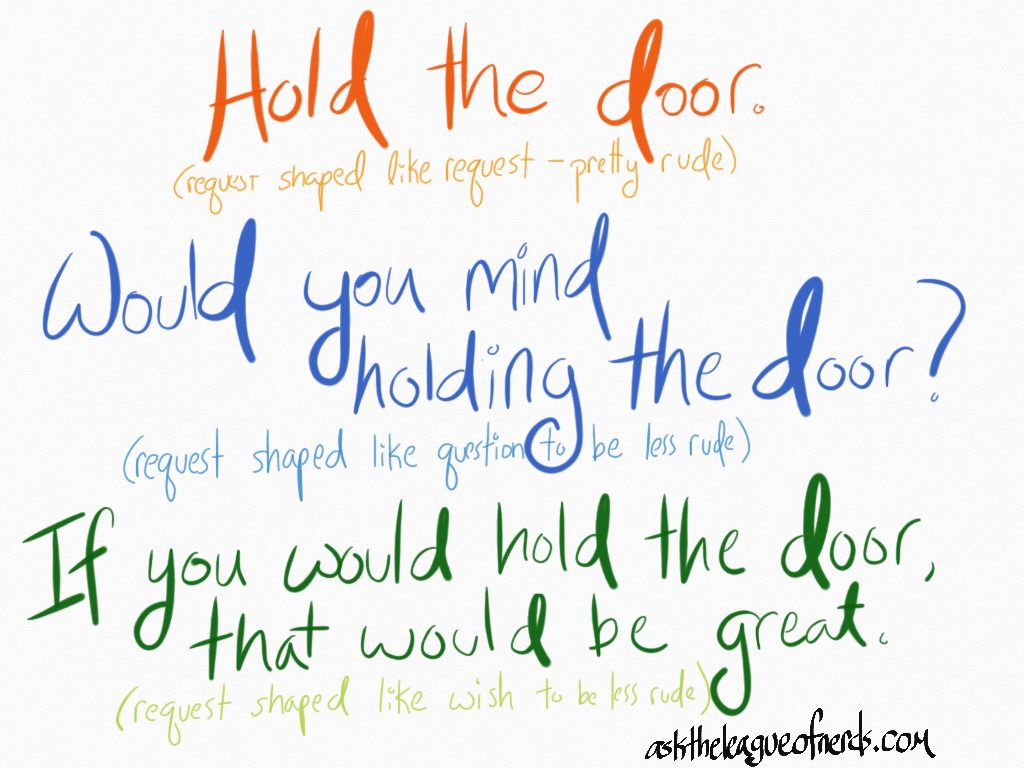

This is a particularly common type of indirect speech act, because it’s more polite. Direct requests are curt and often rude, but requests shaped like questions are ok. “Pass the salt” isn’t terrible, but “Can you pass the salt?” is better. Kids tend to go through a phase where they play with this, and respond with “Yes, I can,” and then they giggle and don’t pass it, and then you swear off babysitting forever.**

Not that being polite is the ONLY option. You could make a request shaped like a question in order to make it much, much ruder. “How many fucking times do I have to tell you to hold the damn door???” (my art)

The important point is that the language alone doesn’t make this clear – it’s all about what’s happening in the real world when the language is being used. It’s possible to imagine scenarios where I’m really asking about your ability to pass the salt – maybe you hurt your arm and I’m not sure you can lift it. But the scenario where I’m making an indirect request is much more common.

Ok, ready for a sharp turn into Serious Consequences and Depressing Legal Stuff? Imagine you’ve been accused of a crime. The fuzz arrest you and take you downtown, sit you in an interrogation room, and read you your rights. One of these is your right to a lawyer, and you think, yeah, I dunno what’s happening here, I should get some expertise on my side. Now, think fast – which of the following would get you a lawyer?

Could I call my lawyer?

Do you mind if I have my lawyer with me?

Can I speak to an attorney before I answer the question to find out what he would have to tell me?

I think I would like to talk to a lawyer.

It seems like what I need is a lawyer.

–Examples from Ainsworth

The answer is none of these. Seriously. These are real examples said by people in police custody, none of which got them a lawyer, and all of which were later accepted by various courts as not really asking for a lawyer.

And they’re all indirect requests. A direct request would be “Get me a lawyer.” But that’s pretty rude, and people mostly don’t want to be rude to the police. So they request indirectly, and like the kid who doesn’t pass the salt, the police in these cases pretended that they didn’t understand. As if the answer to “Could I call my lawyer?” is “Yes, you could” instead of stopping the interrogation and handing over a phone. And all these judges agreed!

Of those examples, the first three are shaped like questions, the fourth as a wish, and the fifth as speculation. But make no mistake, they’re all indirect requests, in the same way that “Could I get some coffee?” and “I think I’d like some coffee” and “It seems like we’re out of coffee” are all indirect requests that mean “go make more coffee.”

So no, your cousin doesn’t need psychiatric help. But maybe you should consider a career in law.

With love,

The Language Nerd

*’s monster, yeah yeah.

**Some pedants never grow out of this.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

This post is drawn mainly from one outstanding book, Peter Tiersma and Lawrence Solan’s Speaking of Crime: The Language of Criminal Justice. Thanks for giving me an excellent reason to finally buy myself a copy!

The examples above are from Janet Ainsworth’s chapter “Curtailing coercion in police interrogation: the failed promise of Miranda v. Arizona,” in The Routledge Handbook of Forensic Linguistics, editors Malcolm Coulthard and Alison Johnson. Ainsworth is one of those few people with both mad linguistics skills and a JD, and basically travels around the world kicking ass and being incredible, and is the focal point of my life goals.

And on that note: I’m taking my kinda-sorta-annual fall break, but instead of needing a month to set up middle-school ESL classes, I’m gonna take some time to adjust to being a new grad student. I’ll be studying — naturally — legal linguistics. Hopefully I’ll be back in a couple months with time and energy to answer y’all’s questions, but I’ve never tried for a PhD before and I make no promises. Wish me luck, and good-bye for now!

Interesting read and much luck with your PhD!! :D

Thank you!

Good luck!

Thank you!