Dear Language Nerd,

I was watching a rerun of Buffy the Vampire Slayer the other day (because that show is great, I hope you do not think otherwise, if you do you are crazy) and I noticed something really interesting in the dialogue. Giles the librarian is discussing the terrible-danger-of-the-moment, the steroids that the swim team coach is giving his team. Comic relief hero Xander has recently joined that team:

Giles: They’re absorbing the steroid mixture through the steam.

Xander: Not they. We. Me!

Do you see it? When Xander changes the pronoun, he first changes “they” to “we,” which makes sense, because “they’re absorbing” changes to “we’re absorbing.” But then he says “me”! You’d never say “me’s absorbing,” you’d say “I’m absorbing.” But if Xander’s line had been “Not they. We. I!” it would have sounded really bizarre. Why does the pronoun case change like that?

From Antony

***

Dear Antony,

Hey, I got no beef with the Buff. Quite the opposite –the linguistics of that show are great! (Remember the one episode where all the adults start acting like teens? And I guess there’s costumes and, like, acting or whatever, but what’s really important is the language change? And the use of teen lexicon and intonation and off-kilter register? That was great stuff!!)

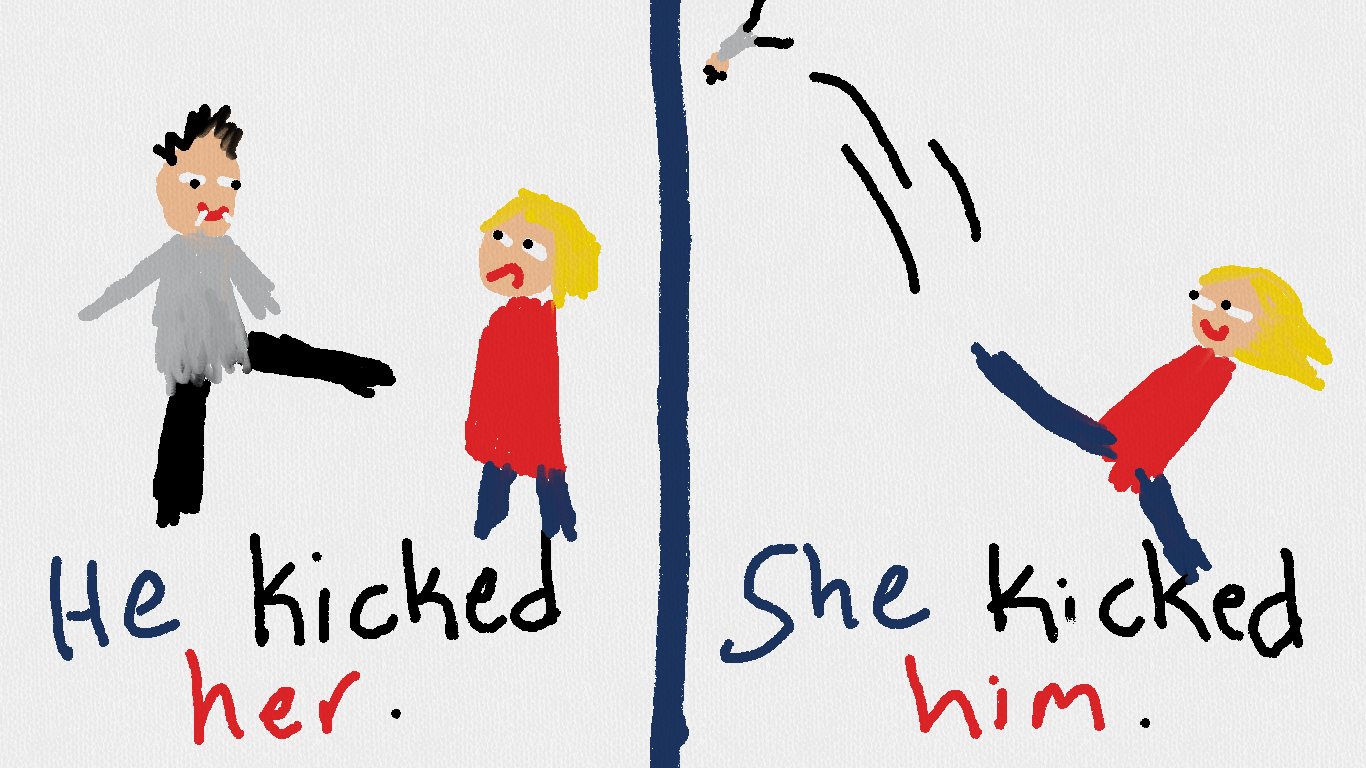

So before we get to the specifics of your question, let’s go over the idea of case, for those readers whose high school English classes are dusty memories. Case marks the job that a noun or pronoun does in the sentence. If a noun is the subject, it’ll be in subjective case. If it’s the direct object, the indirect object, or the object of a preposition, it’ll be in objective case. Usually, the subject is one doing the action, and the object is getting the action done to it. (I say “usually” because some types of sentences, most notably passive, are different.)

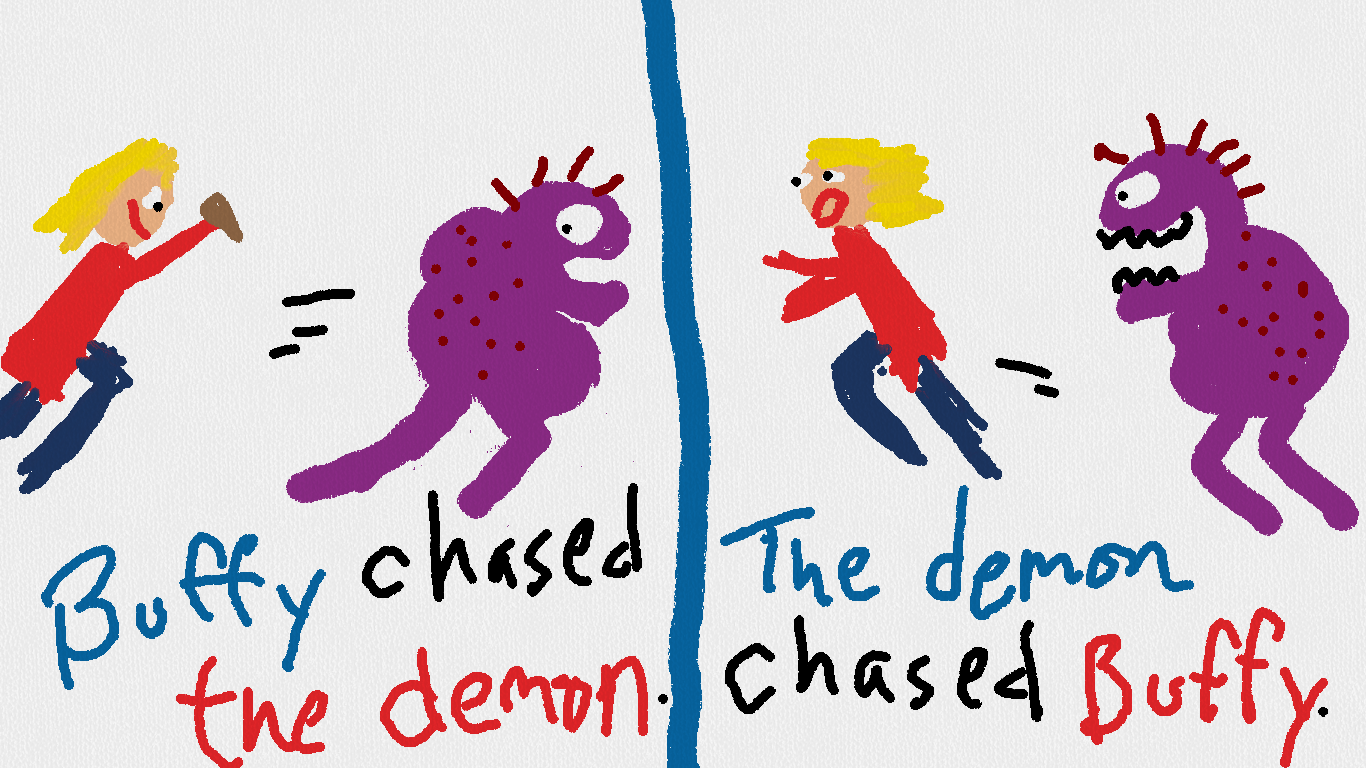

Now, there are a couple of ways for a language to show what case a word is in. We use word order. The noun in front of the verb is the subject, the noun after is the object.

Blue for subject, red for object. All credit for the art in this post goes to me, which is probably painfully obvious.

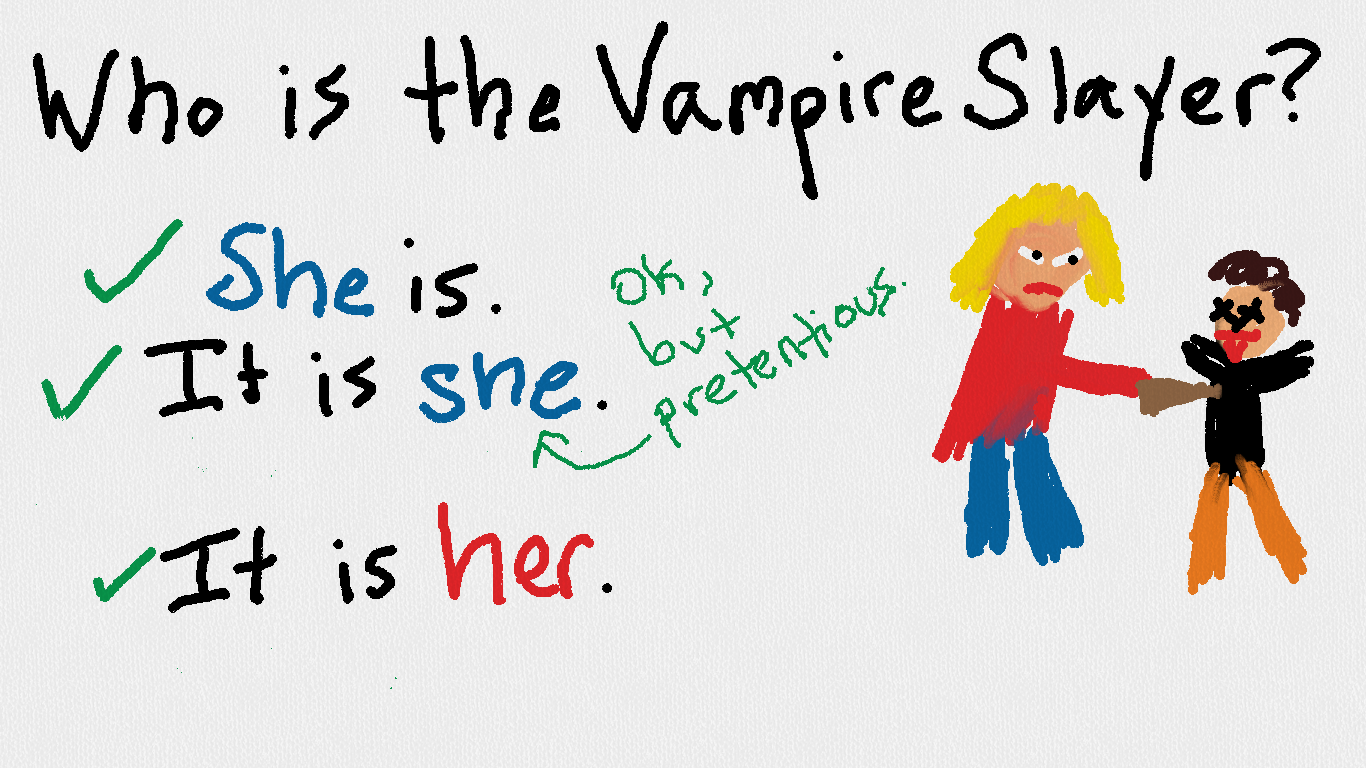

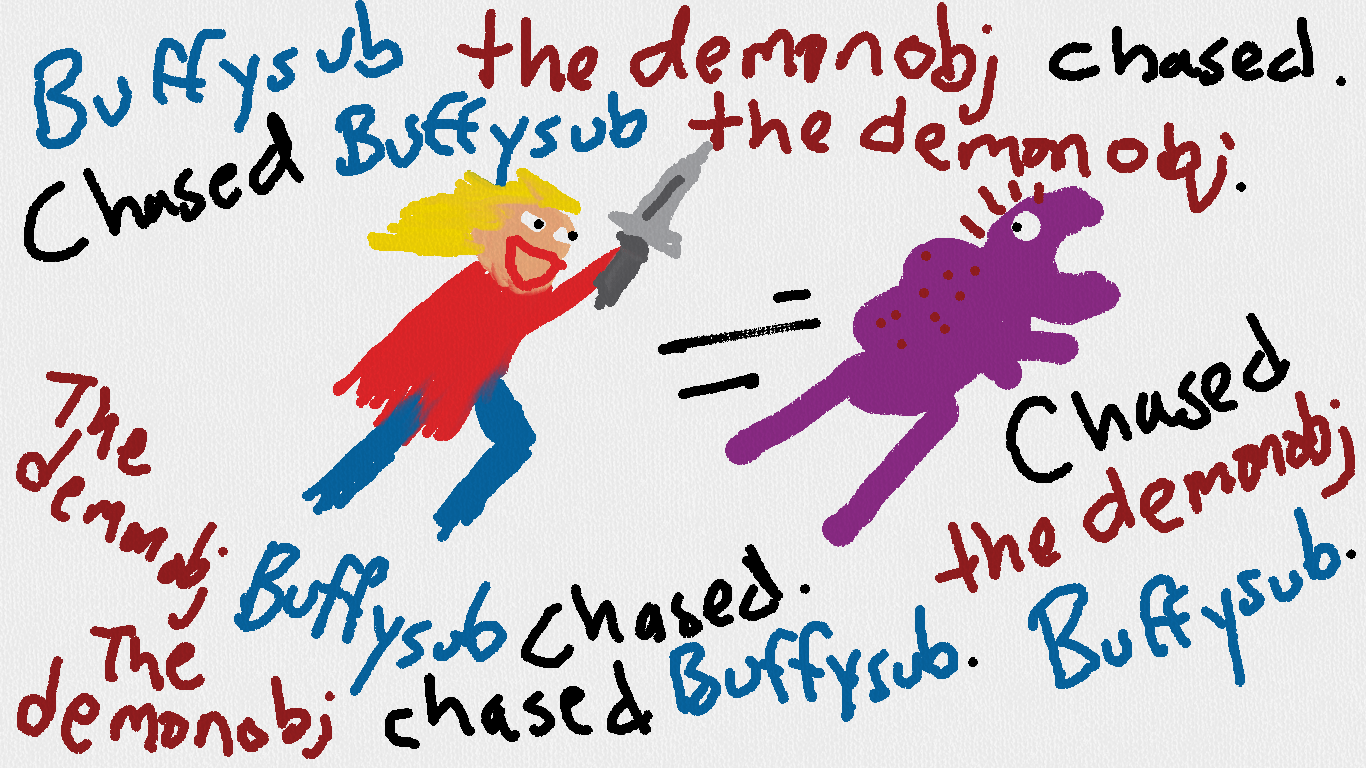

But word order is not the only option! Many languages have little words or word endings that attach to a noun and show what case it is. This is called “inflecting” the noun, and it makes your sentence a little longer, but it has the benefit that you can swap the words around into any order and the meaning stays the same. So if we all got together and decided to start doing things this way, we could put “sub” on the end of the subject and “obj” on the end of the object, and then our word order could just go nuts:

I tried to draw a little Buffy Sub(marine) in the corner, with like a periscope and a stake… ah well.

And now for the kicker! English used to be one of these word-ending-type languages. We used to inflect our nouns like mad, just all the time. We’ve changed to a word-order-type language over time, and stopped putting endings on words… but the pronouns have not forgotten.

The “-m” on the end of “him” and “them” and “whom” is all that remains of what was once a fully-fledged inflective ending.

So now that we have all these nice English-class rules set up, let’s look at the ways we break them when we, you know, actually use language to talk to people. “I” is the subjective form and “me” is the objective, but we don’t always use the first strictly for subjects and the second strictly for objects. If you can think through a sentence and decide logically that “I” (or another subjective pronoun) makes sense, but it feels much more natural to use “me” (or another objective), then you are dealing with a disjunctive pronoun.

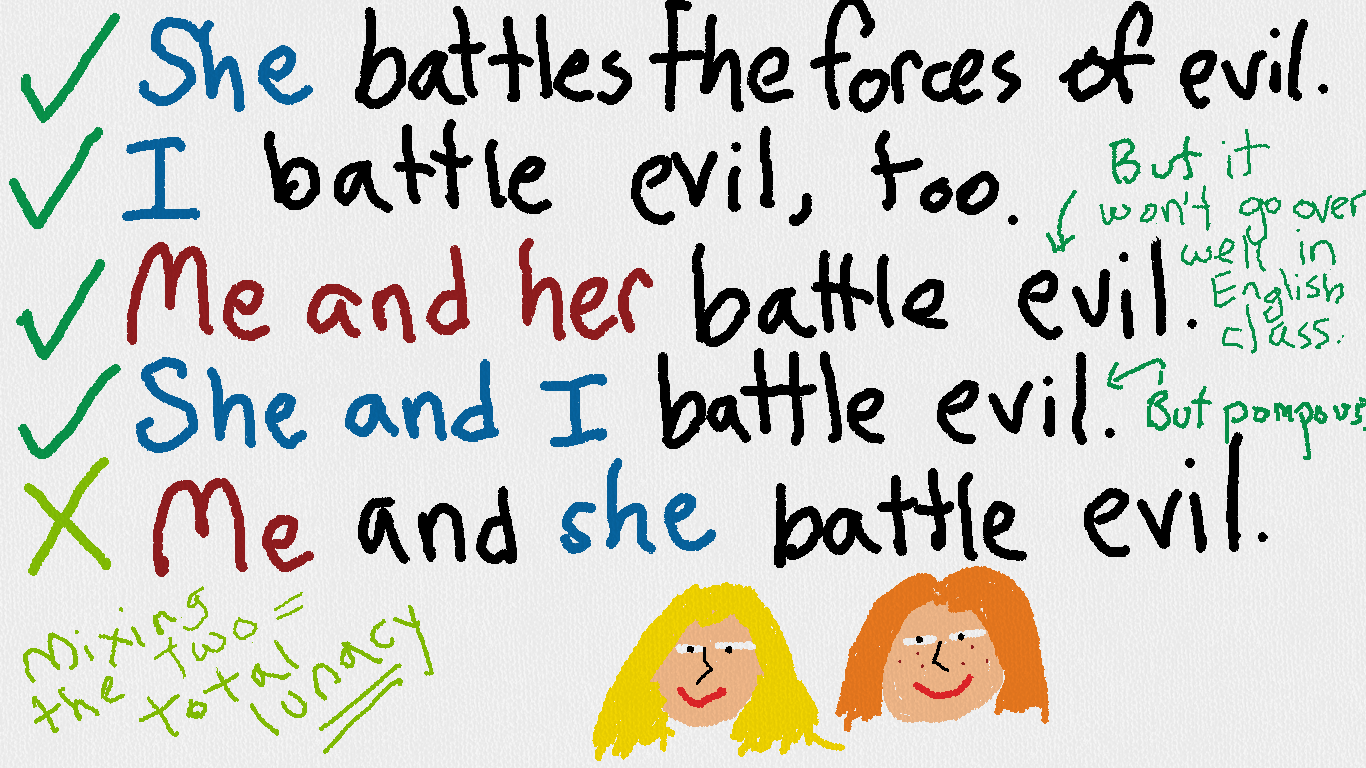

French grammarians have codified their disjunctive pronouns and made a shiny set of (breakable) rules and everyone’s happy, but in English this is not so. Disjunctive pronouns are common in speech, but they are sometimes still looked down on by the language hoity-toity. We’ll go through three examples.

1) This is using the disjunctive pronoun after the copula. The copula is a fancy word for “am,” “are,” “is,” and other variants of “to be.” It’s got a special name because it’s a special verb – instead of showing an action done by one noun to another noun, it equates two nouns. This means that the noun after the copula isn’t really an object, so it doesn’t need the objective case. However, we’re so used to switching to objective case after verbs that we tend to do it anyway, so bam, disjunctive.

2) This is the disjunctive pronoun for coordination, when two pronouns connected by “and” are used in objective case even when they would be used in subjective case individually. So, you would say “He ran away” and “I ran away,” but together it’s “Me and him ran away.” This one is really hated in some circles, but it’s just another possible rule for using disjunctive pronouns. Your grammar crowd prefers “He and I,” but notice that neither the “he and I” group nor the “me and him” group would ever say “me and he” — that doesn’t fit in either set of rules. In fact, it’s pretty likely that everybody would just say “we,” but hey, I ran out of room in my drawing.

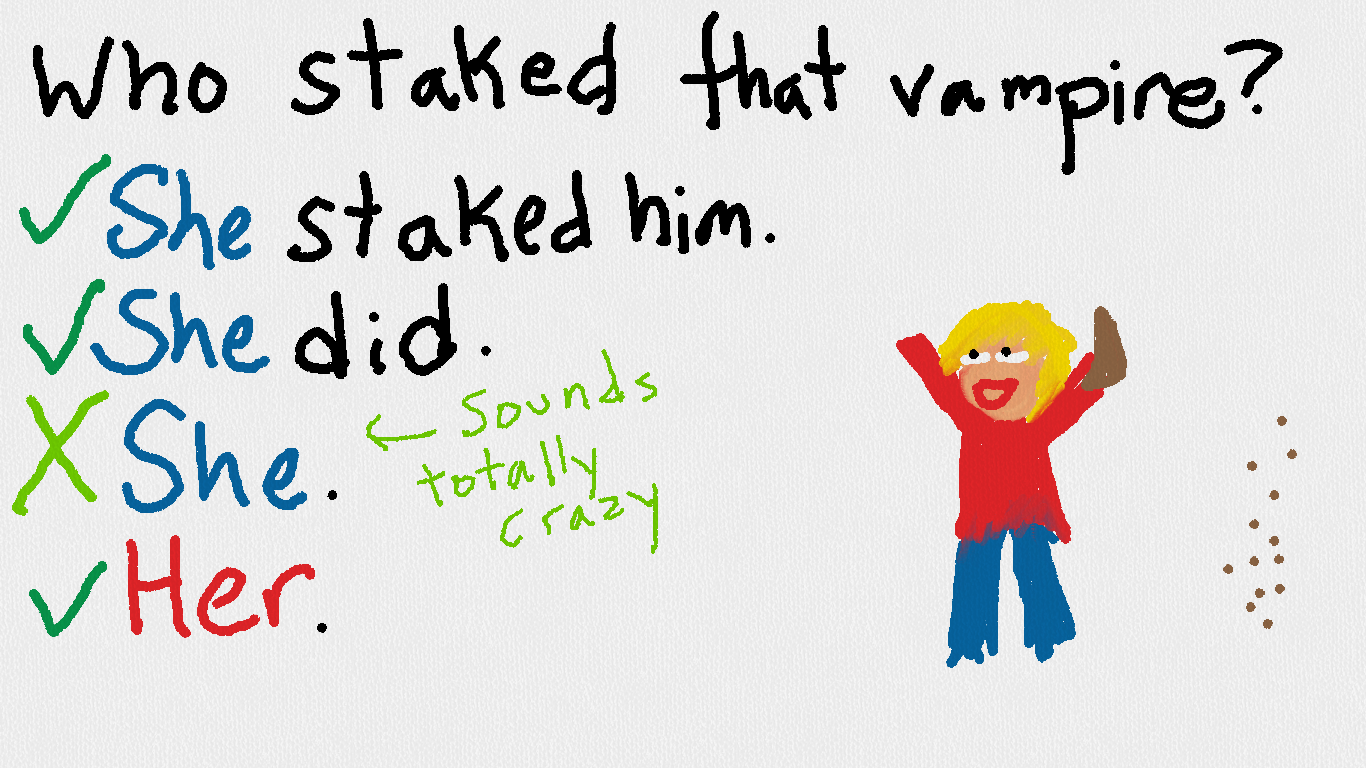

3) This is using the disjunctive pronoun when it’s in isolation. It ends up alone because of ellipsis, which means that you leave some of the sentence out. If you make a full sentence, like “She staked him,” you use the subjective pronoun. However, if you drop most of the sentence (which you probably will — the person who asked you the question one second ago hopefully still remembers it, so you can just give the answer), then “she” sounds peculiar standing on its own. So the rule here is that we swap to the disjunctive “her” when the pronoun is all alone.

Linguistically speaking, these three examples are all the same — variants on when to use pronouns disjunctively. They are all sets of perfectly reasonable rules. But one is required in standard English, one is mostly acceptable and one is hugely stigmatized. Why? Well, one is a common dialect feature of upper-class white people, one of middle-class white people, and one of lower-class black people. Guess who gets to decide what makes it into standard English?

Yeah, that’s right, pronoun acceptability is a marker of institutionalized racism. Didn’t expect that, now did you? I keep trying to tell people, language is serious business.

Now, the example that started this post is of the third type, elision, but that quote has a bit of a twist. It’s not elision from a question, which we’re all used to, but instead elision to correct a sentence, so the first two pronouns are not disjunctive. Let’s take a look at Xander’s deep, deep, deep subconscious as he’s speaking:

“They’re absorbing the steroid mixture through the steam.”

“Not ‘they.’ ”

–I have to use “they” here because I’m quoting what Giles just said. “Them” would be more natural otherwise, but oh well!

“We.”

–Oh, I’m kind of on the fence about this one. I’m not as strongly tied into the quote as I was with the first pronoun, but the fact that the case is subjective is still more prominent than it would usually be. Also “we-me” has a nice rhyme to it.

“Me!”

-The disjunctive-ness is taking over, I’m far enough from the quote that I can’t bring myself to use a subjective pronoun. And “me” is used disjunctively all the time, using “I” in isolation would be pretty strange, it’s gotta be “me”!

Hey, I said deeeeep subconscious.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Or: Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

References this week include A Survey of Modern English by Gramley, the Wiki, and LinguistList’s discussion related to this in their series… called Ask-A-Linguist?! What is this, LinguistList, how could you? But if it’s competition you want, then oh, competition you will get.

My strong commitment to research also compelled me this week to re-watch the episode of Buffy that the original quote came from (“Go Fish”). But then to put it in proper context I had to watch the episodes around that episode, and I believe that there are no shortcuts when it comes to scholasticism, so I went ahead and studied the rest of season 2. In fact, I may need to continue researching season 3 this week, just to double-check my work.

Brought to you by The League of Nerds