Hey Lang Nerd!

(BTW I loved the post about the NATO Phonetic Alphabet)

Is it easier to develop a text-to-speech application for Chinese, rather than other languages, because the tones are already built into the words? Like, wouldn’t that mean that the program doesn’t have to enforce sort of a global tone to the sentence, and it only has to play the sound files for each of the words individually?

Hakan Alpay

***

Dear Hakan,

Thank you! I love this question. I have a tragic tendency to let questions linger in my inbox for months as I slooooowly gather research on them, but this was both interesting and zippy, so here you are, easily setting a new record for Lang Nerd inquiry turn-around speed.

Anyway. The answer’s “nope.” Twice!

First “nope”: is it easier overall to make a text-to-speech synthesizer for Chinese than English? Nah. Some of the issues of English are moot, but they’re replaced with exciting new difficulties.

One big problem for English synthesizers is heteronyms – words that are spelled the same, but have different pronunciations and meanings. Like the sentence “I left my mobile in a mobile home in Mobile.” Three different pronunciations for one word! Rough stuff.

Since Chinese isn’t spelled out in an alphabet like English, this problem doesn’t exist. But there’s an equal or greater challenge in dealing with Chinese characters. If a machine reads 行, it’s gotta figure out if it’s pronounced xíng, háng, or héng.

But that’s general stuff. Let’s get to the meat of your question, and the second “nope.” Speech synthesizers have come a long way since Wolfgang von Kempelen used a bellows and a bagpipe to sorta almost make vowel sounds. On the whole, synthesizers are now intelligible – you can understand what they’re saying. The current challenge is naturalness, making the machine sound like a human voice. And the difficulty with that is prosody.

Prosody is overarching sound. Not the sound of a letter or a word, but of a whole phrase or sentence, what you called a “global tone.” How and when people pause, what words are louder or softer or shortened or lengthened, these are parts of prosody. What we need to get into here, though, is pitch. Some parts of a sentence are said with higher or lower pitch relative to other parts.

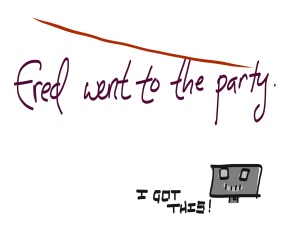

Text-to-speech synthesizers have a hell of a hard time with this, because we use it so often, in so many different ways. A simple declarative sentence will have one contour – one shape for its pitch. It’ll start higher, and end lower. Most synthesizers can do this. Sometimes it’s all they can do.

But just throwing “and” in there will confuse a machine. We know that this is now two parts that need two contours, but a synthesizer won’t. And if you give it a new rule, saying to break a sentence into two contours when it sees “and,” then it’ll make new mistakes.

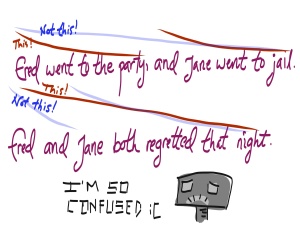

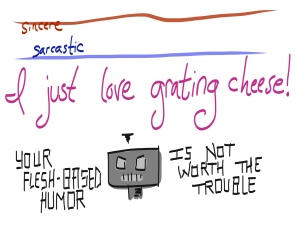

And this is the simplest example! We start low and end high when asking a yes-or-no question. We use high-low-high to show that we’re not sure about something (this is why “I don’t know” can be shortened all the way down to “Ahunno” and still be understandable; the pitch carries the meaning). We get higher with excitement, and we use a low, flatter pitch all the way through a sarcastic comment, which can be so subtle that it confuses humans, much less machines.

There are so many pitfalls for the unwary HAL-wannabe, and this is why synthesizers still sound so, well, computerized and unnatural, despite all the advances being made.

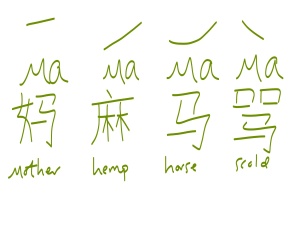

Now, this has all been about prosodic pitch. What you’re referring to in Chinese, and I think we can safely say Mandarin Chinese, is lexical pitch. This is the tone that’s part of the meaning of the word. There are four tones in Mandarin, and since I don’t know one iota of it myself, I’ll use the most common example, “ma.”

So how high or low your pitch is when you start compared to when you end changes the meaning drastically.

“Doesn’t that still make it easier??” I can hear you asking. Doesn’t that mean each character has one tone, and then you’re done?

Nope. Nope nope nope. It makes it worse.

Mandarin uses lexical and prosodic pitch. Your synthesizer needs to be able to take all those lexical pitches and overlay them onto a larger pitch contour. The overarching pitch contour needs to be clear, and each individual tone needs to be discernible, too!

Really, text-to-speech synthesis is nothing but trouble all the way around. But hey, if you’re fascinated by these challenges enough to want to take them on yourself, then there’s about six zillion places hiring.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

Rarely has so much research made so short a post. First, general English prosody:

http://kochanski.org/gpk/prosodies/section1/ — Lovely sound clip examples here!

English text-to-speech:

http://www.explainthatstuff.com/how-speech-synthesis-works.html

www.cs.columbia.edu/~julia/files/ELL05.doc — A great little summary of prosody issues by Hirschberg, should open as a doc

Prosody in Mandarin Chinese:

http://www.semioticon.com/virtuals/talks/chow.htm

http://elanguage.net/journals/lsameeting/article/viewFile/2871/pdf

And then there are fascinating-looking articles on Mandarin text-to-speech by Jianhua Tao, but I haven’t been able to read them yet, because somehow researchgate does not immediately recognize the League as an institution — madness!

Wow, this was an amazing article! Very sorry for arriving back so late, I didn’t think you would be able to write this so fast! Its amazing that even though there are so many languages in our world, they all follow similar patterns of prosody based on the context and purpose of the sentence. I only figured that tonal languages like Chinese had no prosody (or “global tone” lol) because when I heard it spoken while I was first learning it, it was difficult to figure out the main “flow” of the sentence, it sounded like each word’s tone was overriding the prosody. But now I see that there really is prodosy in Chinese (and I imagine it could be similar to that of English, given their similar grammatical systems).

I guess then it would be harder to make a text-to-speech program for Chinese. But in a way, I feel like it would also make it harder to learn the language? Because you would have to grow a feel for the threshold (or opacity, so to speak) between the word’s tone and the sentence’s tone, so that you would be understood completely, and yet would not sound like a robot. Really interesting stuff! And btw I love the cute illustrations in this one! This is one of the only times I have felt sympathy for a speech synthesizer ahaha!

Haha, I’ve got questions in my queue that are over a year old, so counting on me for timeliness is unwise. This one just stuck with me!

The prosody in Mandarin isn’t exactly like English, though I guess my picture makes them look the same… I was trying to show the differences in having or lacking lexical tones, but I may need to go back and edit that. This website has examples of declarative and interrogative sentence prosody in English and Chinese (and Russian, just for kicks): http://kochanski.org/gpk/prosodies/section1/type.html Neat stuff!

If you’re coming from a non-tonal language, then those lexical tones are definitely going to stick out and feel much more obvious, just because they’re so different. But yup, gotta find a balance between the lexical tone and the sentence intonation. Good luck with your studies!

I doubt my answer to your other question will be QUITE so speedy, but I’ve got it in mind!