Hey Language Nerd,

I was waiting for a friend last night, and when I messaged to ask him where he was, he answered “Oscar Mike.” Apparently that meant he was coming, because he got there soon after. But I don’t get it. Do you?

-RPD

***

Dear Romeo Papa Delta,

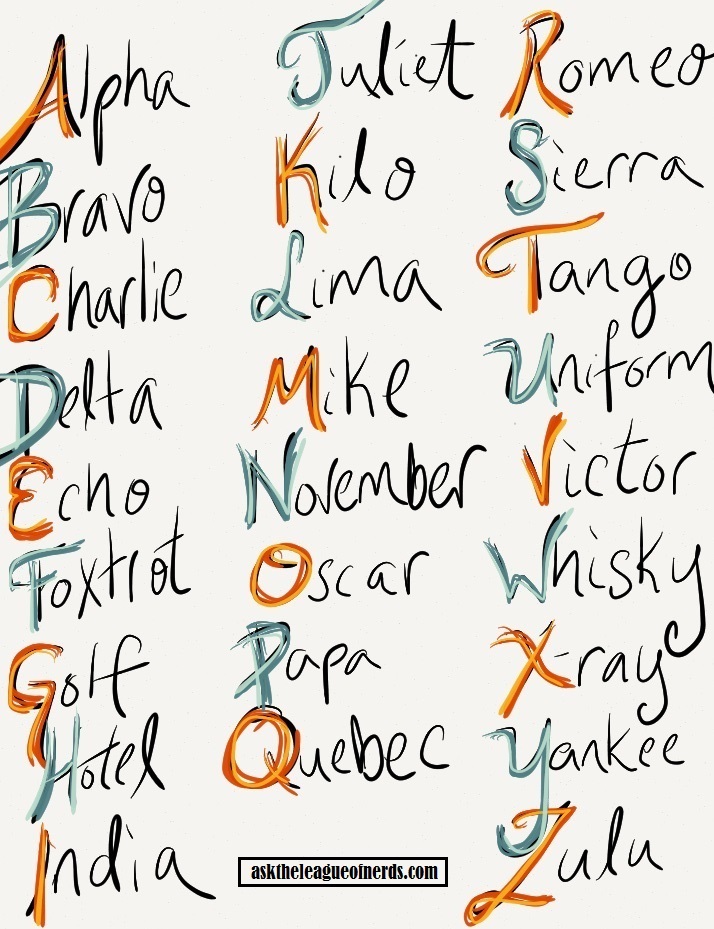

In fact I do. It’s military slang for “on the move,” which has made its way into civilian life through, according to TV Tropes, mostly Call of Duty. “On the move” is shortened to “O M,” which is said “Oscar Mike” in the military alphabet. That’s where all that Alpha Squad, Company Bravo business in every war show comes from.

The military alphabet is often called the NATO Phonetic Alphabet, which is weird, because it is not phonetic at all. I’ve talked in previous posts (at length) about the International Phonetic Alphabet, which actually is phonetic. Here’s the difference: the IPA is about sounds. The military alphabet is about spelling.

The letter “c” makes four different sounds in the words “cake,” “exercise,” “machine,” and “cheap.” So in the IPA, it’d be written with four different symbols – specifically, /k/, /s/, /ʃ/, and /tʃ/. But because they’re all spelled with “c,” if you were using the NATO Not-Actually-Phonetic Alphabet, you’d say “Charlie” for all four of them.

It’s not hard to memorize these guys, and being able to throw them out quickly sounds damn cool, so here you go:

If you just had a blinding realization about Dollhouse, you’re welcome.

But besides pestering your colleagues by calling them by their NATO initials,* what’s the point of this alphabet? Well, language is a trade-off between getting information across quickly and getting information across clearly.** The more information you send in a shorter time, the higher the chance of misunderstanding.

Languages find a balance – it’s not something we do consciously, but there are enough built-in redundancies in English that we can understand each other even when speaking quickly, or hanging out at a rock concert, or whispering. But the stakes in normal speech usually aren’t too high, especially when it comes to spelling. We spell out our names over the phone, and the occasional new word we recently learned (brummagem!), but if we’re not understood, worst case scenario, we repeat it four or five times and get hella annoyed.

But the English’s normal balance between speed and clarity doesn’t work in every situation. If a military commander is telling a subordinate which grid square of a map they’ll meet at, or a cop is radioing in a license plate, or a ship is sending a distress call, they need to skew towards making sure the information will be clear. In speech, “B” and “V” are easily mistaken for each other; “Bravo” and “Victor” are not.

Of course, once you’ve got a slick alphabet like this going on, slang is bound to come out of it. “Oscar Mike” illustrates the form: a phrase is shortened to an acronym, which is then spelled out alpha-bravo style. One thing’s unusual, though — no cussing. Most of these expressions are workarounds for something less polite, like “Alpha Charlie” for “ass chewing” or “Charlie Foxtrot” for “clusterfuck.”

Or the sign-off that the A-Team taught us all: Alpha Mike Foxtrot.

Yours,

Tango Lima November

*Not that this has played any part in my research for this post.

**This post is a miniature example of the dynamic I talked about in that massive post about language rates last summer.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

References, once more with feeling! More about the NATO So-Called-Phonetic Alphabet and its origins here. Wiks has a cool list of prowords here, and here’s a site with more military slang. Language redundancy resources abound (here’s one), though I first learned about it, and so many other things, via Steven Pinker. And here’s that link to TV Tropes again, which is where I’ll be for the rest of the night. Place is a black hole, sucks you right in.