Dear Language Nerd,

Why do news anchors and the like say “an historic occasion” when they would never say “an history book”?

-JRS

***

Dear Jurs,

Because it’s fancier. But not because it’s right.

First, let’s go over what the “a/an” rule really is, and super-double-first, let’s go over what it isn’t: it isn’t a spelling rule. Here we see again the subtle and insidious weaving together of speaking and writing in our minds, that Great Consternator of linguistics. “A/an” is a talking rule. “A” comes before consonant sounds, and “an” before vowel sounds. If you try to make this a spelling rule, you’re going to need a list of exceptions and of exceptions to exceptions; you can spell a consonant sound with a vowel, and vice versa, because English spelling is not for the weak. But as a talking rule, no prob.

So, for example, we say “a unicorn” and not “an unicorn.” Even though that sure looks like the famed vowel <u> up front, we ignore the spelling and instead care about that initial “y” sound we pronounce it with, “yoo-nee-corn.” Or /’junɪkɔɹn/, if you read the phonology posts. Similar for “a European” or “a one-way street.”

Going the other way, we find the silent “h.” We say “it’s an honor to meet you, Mr. Unicorn,” because the “h” in “honor” may as well not be there for all we care, we are moving straight to that “o.” If the “h” does make a sound, as in “haberdasher,” we stick with “a.”

Exactly how (or how often) h’s are pronounced varies. Some places drop more, some fewer, and it fluctuates with time. British dialects drop more h’s than American ones, and everybody dropped more in the past than they do now. For a thorough case study of one such dialect, please refer to My Fair Lady (“Just you wait, ‘enry ‘iggins, just you wait!”). If a group drops the “h,” it makes good sense to use “an” – “an ‘istoric event,” “an ‘istory book,” “an ‘otel.” And indeed, most of the time “a/an” just varies naturally with the pronunciation.

“An historic” as almost-the-only exception to a very solid rule has never really been recommended by anybody. For over a hundred years, style manuals and grammar books have plugged “a historic.” So why exactly it became a thing is a bit of a mystery, rather like hating “hopefully.” It it hasn’t been researched much, though James Harbeck did a nice paper on it, and it makes not much sense.

The clearest possibility is that the British and other folks who did drop the “h” wrote down “an historic” on various scraps of paper, and Americans and other (or later) non-droppers saw that, figured both that anything British was prestigious and that writing and talking were the same, and then plumped for it in their speech, too. Then the idea of markedness enters the picture – that means simply that if you see someone using a grammar structure that’s weird to you, you’ll guess they’re doing it for a reason. If “a historic” is the unmarked, unnoticed, normal form, and the hoi polloi are saying “an historic,” they must have a good reason for it, right? It’s pyramid scheme that a certain group of speakers seem to have pulled on themselves.

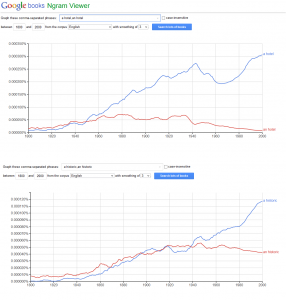

There were more of these words in the past – “an hotel” used to be big. Harbeck suggests that “an historic” may have stuck around because of the very nature of the word. Since it tends to get used when something important (or, er, historic) is happening, the markedness is even stronger. But it and the other “an+h” words are vanishing quickly, and we can watch them go via the magic of Google Ngram.

And even if no one is listening to their style books, maybe they’ll pay attention to a different authority. Backstory, the Greatest History Podcast Out There, recently decided to refer to their guests using “a historian” – and if they’re done with “an historic,” it’s history.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

Check ’em out: James Harbeck’s An historic(al) usage trend, and Backstory’s own kerfuffle on the matter.