I have an unpleasant acquaintance, an American learning Chinese. He was mocking another student of Chinese, a woman with a Southern accent, saying the accent carried over into her (advanced) Chinese, “Neeeee haa-yoh,” and so on. I don’t know her, and I don’t know Chinese, but this really burns me up. So my question for you, Language Nerd, is: does speaking a regional dialect in your native language really affect foreign languages you learn? My theory: only if you’re making shit up.

DDD

***

Dear Trip-D,

My gut says this guy is probably just being a d-bag. My gut has two reasons for this. One, I’ve had similar unpleasant encounters, and it’s always a language-learner making fun of another language-learner, never a native speaker of whatever language they’re learning. Two, imagine it the other way around. An American meets a native speaker of Chinese, and they talk in English. Is the American going to know whether the Chinese person is from Beijing or Guangdong, based solely on the accent in English? Hella unlikely.

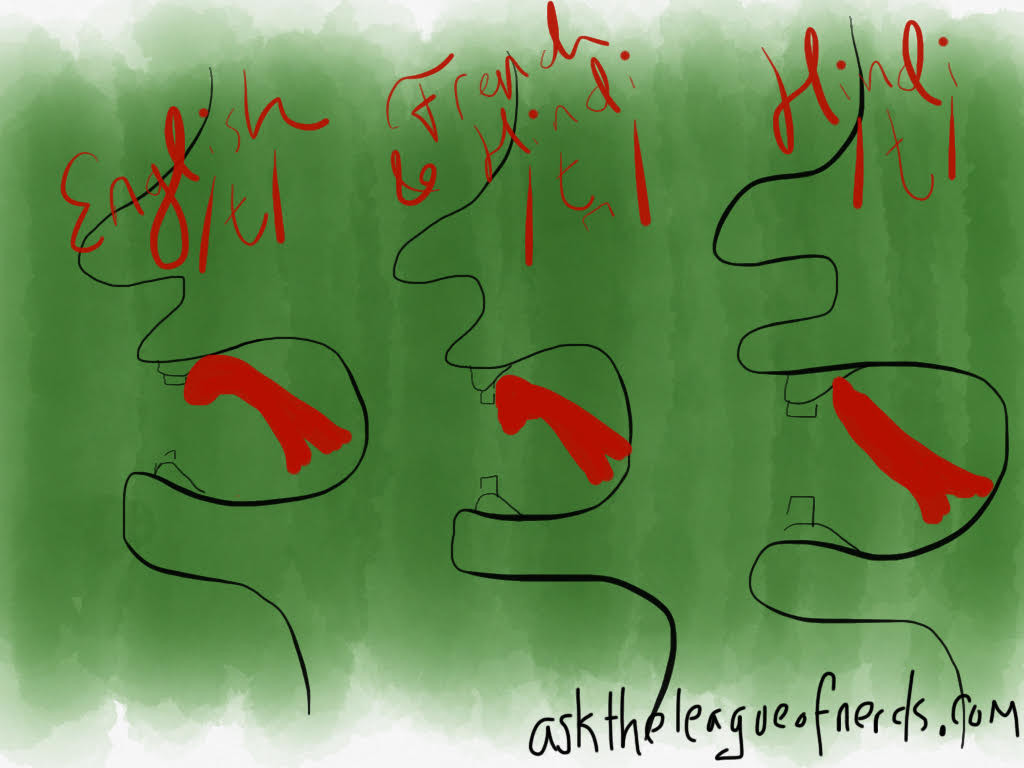

But let’s get the gut out of the driver’s seat and think logically. We need to talk about what causes a foreign-language accent in the first place. Much of it has to do with carry-over from our native language. When we learn our native language as teeny adorable babies, we pick it up naturally – the grammar, the words, the prosody, and most important for this topic, the phonemes (see here for phonology basics). If we’re babies in an English-speaking environment, we’ll figure out that putting the blade of our tongues on that gum ridge behind our teeth to stop our airflow makes a sound that the people around us recognize as /t/. We don’t think about it like that – we’re babies, man, we barely think at all – but we do it.

But when we learn a second language, especially when we’re older, we’re not starting out fresh like babies do. We’ve already got the phonemes of our first language knocking around inside our heads. And we tend to try and use these first-language phonemes, even when the language we’re learning doesn’t make them in quite the same way. In French, for example, /t/ isn’t made on that gum ridge; the tongue is directly on the teeth, which we can show by adding a little bump to the symbol: /t̯/. A native English-speaker is liable to substitute the English /t/ when speaking French, and a French speaker might use /t̯/ when speaking English. A small difference, sure, but many small differences add up to an accent.

And English and French share a lot of history, and a lot of sounds. The more different the languages, the more noticeable the effect of using odd phonemes. Hindi has one /t̯/ that’s the same as French, and another, /ʈ/, that’s made on the gum ridge like English, but with the tip of the tongue instead of the blade. If a native English-speaker uses /t/ for both of these when speaking Hindi, it’ll make for a distinctive accent. And vice versa: native Hindi-speakers talking English often have an equal and opposite distinctive accent.

We three T’s, of alveolar / hit that ridge, or maybe molars (not really, it’s the incisors, but that doesn’t rhyme now does it)

It’s possible to learn new tongue-twists as part of a new language, but because shaping our mouths to make sounds is an unconscious process (okay, you’re thinking about it now, but I mean normally), it’s very, very difficult. Other parts of the native language, like grammar, can have this kind of carry-over effect, but phonology is the most entrenched.

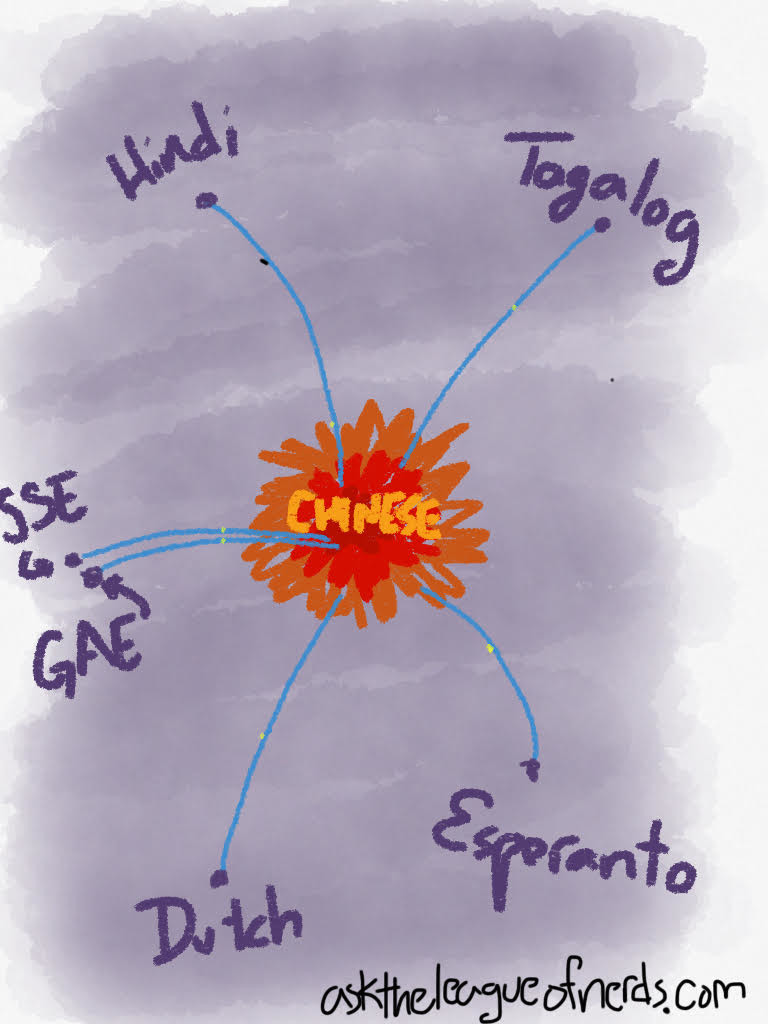

Two different varieties of English probably do have slightly different foreign-language accents, for the same reasons that two different languages will lead to different accents. I’ve talked previously about how wiggly the boundary between a dialect and a language can be; two dialects splitting off and growing further apart creates different languages, like the Romance group growing out of Latin, so there’s a spectrum from “barely different” to “can’t communicate.” (At the latter point, they’re different languages.)

Southern States English is definitely different from General American, but speakers of one can understand speakers of the other without difficulty. They’re not going to be separate languages anytime soon. And there are some phonological differences, but it’s just not a huge number. Mostly vowel stuff.*

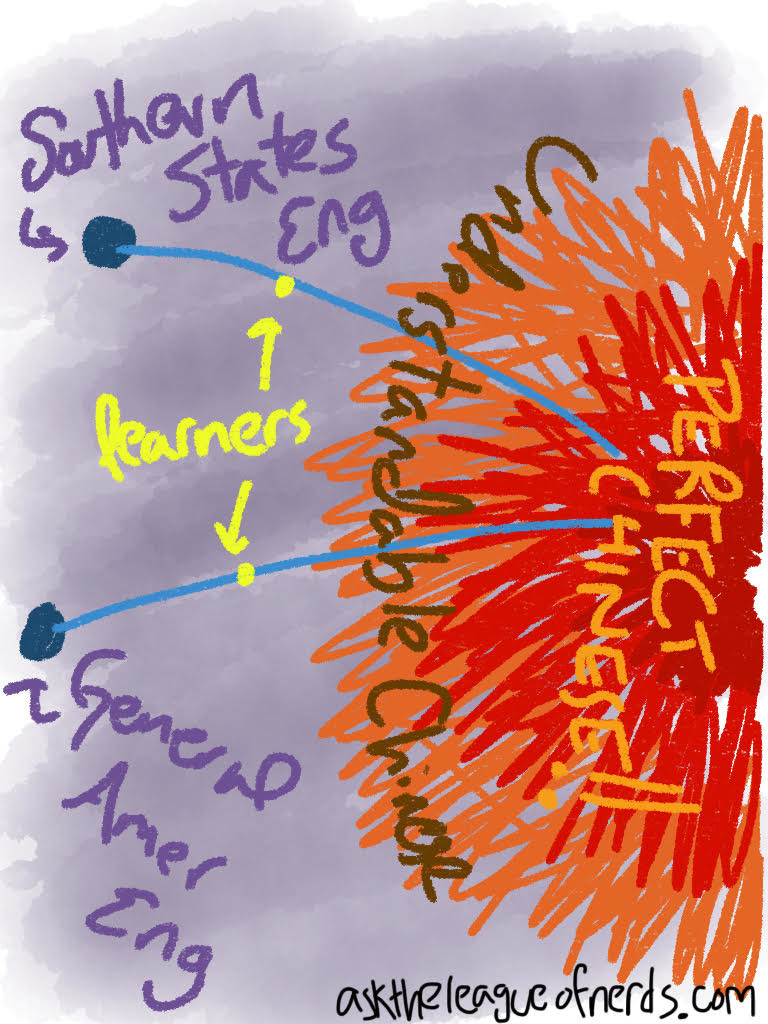

So why does a certain breed of cretin find this funny? I have two ideas, one charitable, one not. The first is that the comparatively minor differences in regionally-accented Chinese may loom large in the mind of someone aware of that dialect. Everyone’s aiming to sound like a native speaker, but adult learners by and large don’t get there. Some of the sounds of the native language peek through, and if she’s carrying over Southern vowels while he’s carrying over Standard ones, maybe that difference feels like this:

The Orbital Path Directly to the Core of Well-Learned Phonology. This metaphor makes perfect sense. y’all.

Even if the reality is more like this:

My other guess is Reverse Language Stereotyping. Language stereotyping is when someone hears another person’s speech and makes assumptions about their character based on it; reverse language stereotyping is when someone knows something about another person (for example, that she’s from the South) and then hears what they expect to hear in the person’s speech, whether or not it’s really there.** So could be that your acquaintance knows this woman’s from the South, wants a reason to ridicule her, and convinces himself he hears a Southern accent in her Chinese.

Dicks gonna be dicks.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*Hey, I wrote about this before too.

**And I wrote about this one! Wow, I was super well-prepped for this post.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

Here’s the Wiks on Hindustani and French phonology. It’s the laminal denti-alveolar and the apico postalveolar plosives, if you’re curious.

I wandered all across the internet looking for hard evidence for this post, but found not a stitch. Hence the speculative nature. Any solid research would be great for either making or disproving my point – if anybody out there knows of any, send it in, by Jove!