i want to learn japanese but i cant understand the alphabet :(((

***

Dear Anonymous Would-be Otaku,

First the good news: no need to beat yourself up for not getting the Japanese alphabet – there ain’t one! So no worries there.

Now the less-god news: there are two syllabaries and a whole slew of logograms instead. Yup, three different writing systems. But still, don’t panic. Take ‘em one at a time, and start with the hiragana.

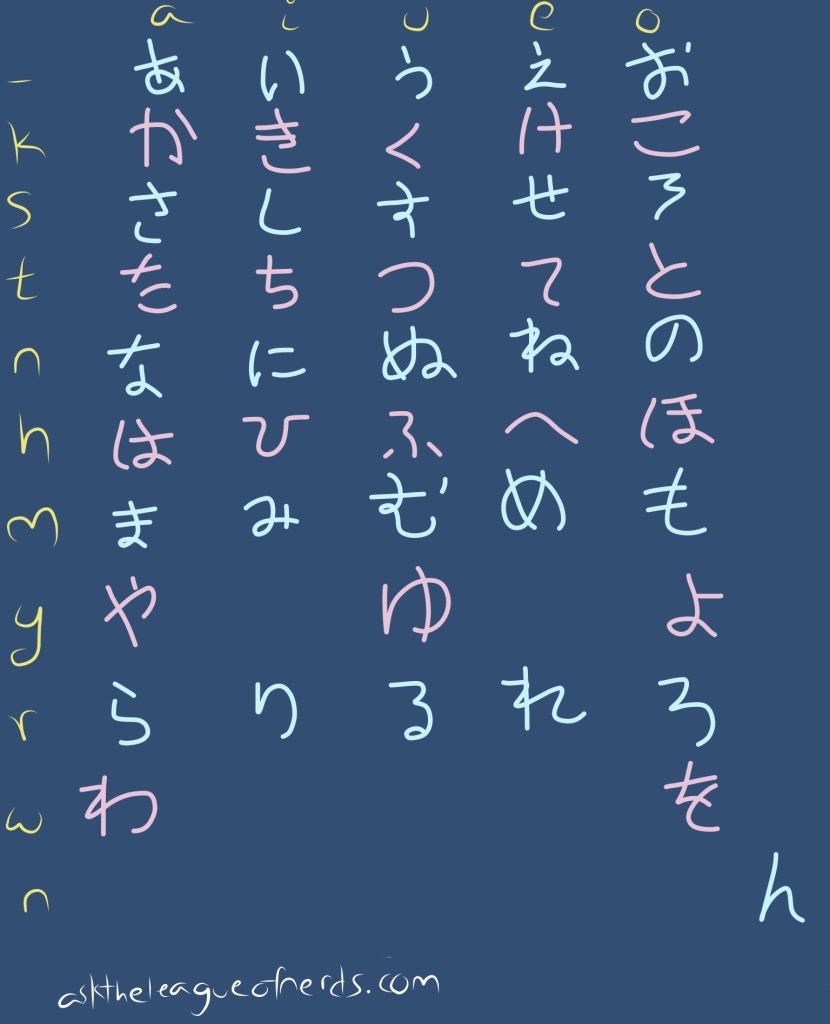

The easiest bit is the vowels. There are five: “a” as in “father,” “i” as in singing “do re mi,” “u” as in “thru,” “e” as in “beg,” and “o” as in “yo.” And each of these gets their own symbol.

More the Spanish-y vowel sounds than the English-y ones.

Sure, they’re nothing like our symbols, but the concept is the same: a shape to represent a sound.

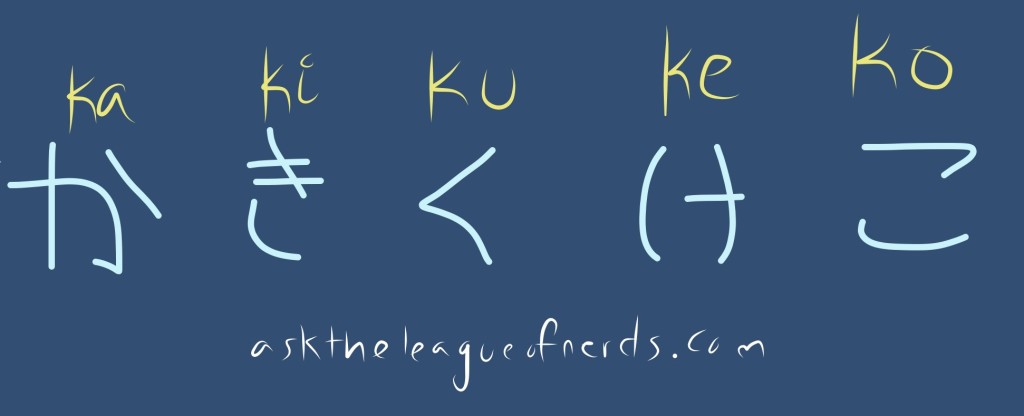

It gets a little weirder in the next step. In English, consonants get their own separate symbols, like “k.” Then if we want to show a sound like /ka/, we just slap the “k” and “a” together and write “ka.” But in Japanese, consonants don’t get their own symbols. There’s no way to write the /k/ sound alone. Instead, it must be paired with a vowel, and that consonant+vowel combo gets its own, new symbol.

There’s no connection in the forms of the hiragana in this group, nothing to show that they all start with /k/. For that matter, there’s nothing to indicate a relationship between “a” and “ka,” either.* Each symbol of the hiragana is unique. And yeah, that means you have to memorize them, but hey, there aren’t too many.

Dang, some of these are buttugly. Don’t rely exclusively on my chart, y’all.

Not the twenty-minutes-tops that it’d take you to pick up the Korean hangeul, but you could knock these out in a long weekend.

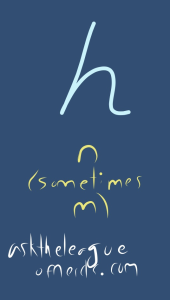

A couple things to note about the chart. First, ち, つ, and し are “chi,” “tsu,” and “shi,” not the expected “ti” or “tu” or “si.” Second, there are implications for the structure of Japanese words. Since every consonant comes attached to a vowel, you can never have two consonants together, or a word that ends in a consonant. With one exception –

Someone’s always gotta make trouble.

— they’ve all got the same C+V pattern. This is why English loanwords like “remote control” get stretched out to “rimooto kontorooru.”** Can’t let that “t” and “r” stick together (though the “n” is ok), and can’t end with a consonant.

Third, this really isn’t that many different sounds, now is it? Surely not enough to say everything. So where’s the rest? Don’t worry, you don’t have to memorize any more (yet). We just adapt the hiragana, and very handily, too.

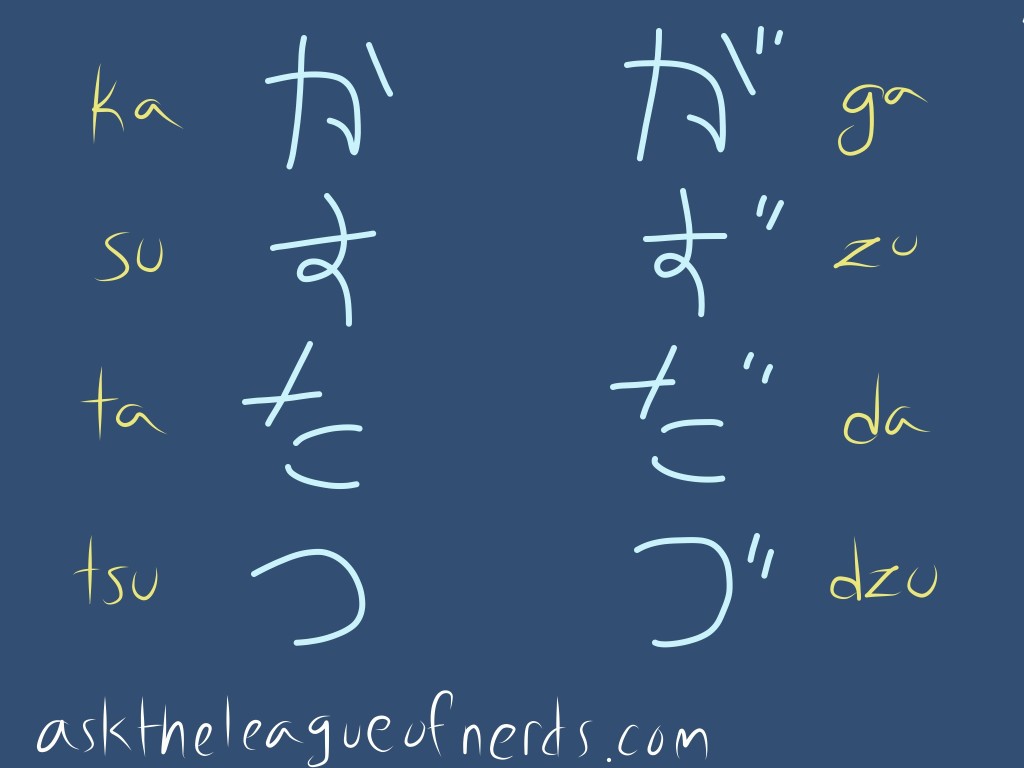

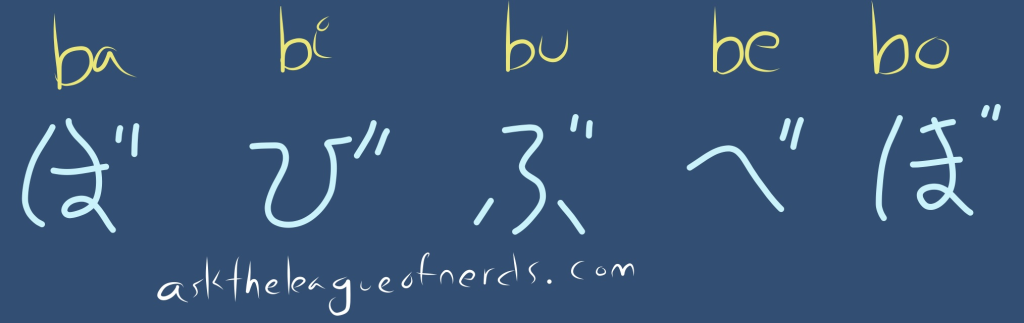

As we’ve discussed at length before, many consonants come in pairs, voiced and voiceless (if that means nothing to you, head here and check back later). In English, we don’t systematically show this in writing – nothing in the shapes of “k” and “g” show that they’re connected. But Japanese does. All the hiragana we looked at above are voiceless. To get their voiced counterparts, just add two lines.

There’s an exception to this rule too, or at least half an exception. If you put the voicing lines on the “h” row, you get “b.”

“Bae” does not yet have a single symbol.

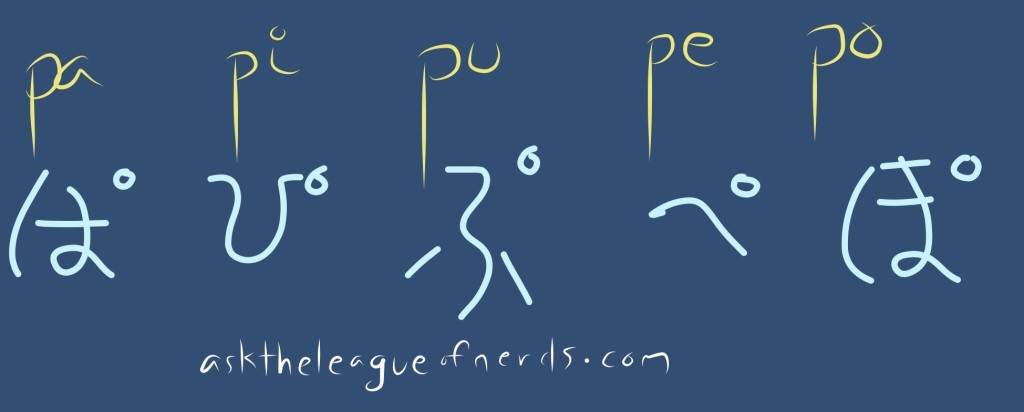

But the voiceless buddy of “b” isn’t “h,” it’s “p”! So where are the p’s?? Don’t we have them? Can’t we trust them? Come on, they just need you to believe in them!

Allllll I am saaaaaying…. is that you can finish this terrible pun for yourself.

So there are circles to show the p-group. That’s a one-off.

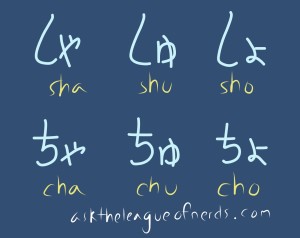

Last thing (and it is the last thing, I swear). I mentioned a minute ago that ち is “chi,” but it’s a loner. What if you want to write “ch” with another vowel, say “chu”? Or “sh” with something, like “sha”? Well, you take the vowel you want out of the y-group symbols and write it in mini letters. Kinda odd, but there it is.

As in “Pikachu,” a mouse that ate the world like twenty years ago, kids.

Oh, crap, there’s one more last thing. Drat. You can also write つ “tsu” in mini letters, and this means the next consonant is longer than usual. But that’s it! Really!

So your hiragana are good, and you’re all set to wander off into the wide world of Japanese writing! Except for those other two writing systems that you’re also gonna need. Dang, Japanese sure front-loads the work.

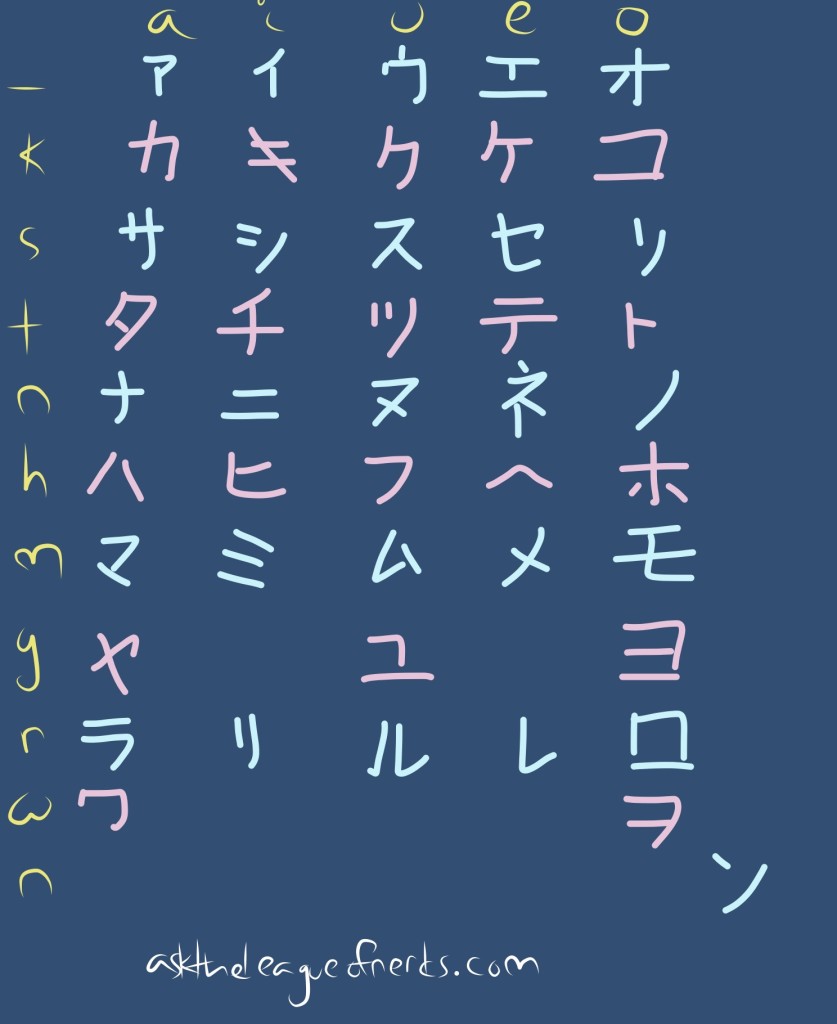

Well, once you’ve got the hiragana, system #2 is easy. That’s the katakana, and it works the same way as the hiragana. It’s just a different set of characters for the same sounds. Kinda like how we have two different symbols for /b/, “b” and “B,” and we use them in different places. In Japanese the sound /ba/ has hiragana ば and katakana バ, and you use those in different places. But it’s the same chart, and has the same rules about voicing lines, circles for “p,” mini-letters for “sha,” and so on.

But these guys are much pointier!

And then there’s the last system, the kanji. Uh. Heh. The kanji.

Hoooo.

You know what? You get these first two settled down in your gray matter, then hit me up again and we’ll talk kanji. It’s just a whole other damn thing, and two things at a time is enough to start with.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*For scripts that do show these relationships in the form of the letters, see abuguidas, here.

**And then, because it’d be a pain to say that all the time, re-shortened into “rimokon.” But the ways and wiles of shortening words are a tale for another day.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

This post comes straight outta college, from hella memorable Dr. Ochiai. The textbook we used was Genki.

If you’re already moving into kanji, there’s always Heisig, and this post on general vocabulary memory tips might be helpful too. And for anyone learning Japanese, the place to be is All Japanese All The Time.