Part 1 (A Matter of Some Consonants) is here.

Alright. Vowels. Much like last time, in this part we’re going to go over how English vowels work, so that next time we can talk about what other languages do differently. (No, I haven’t forgotten the original question, and we will get there… eventually.)

In the previous post, we needed to know three things to talk about consonant phones: where in the mouth they were made, whether the vocal chords were vibrating or not, and how they were affecting the airstream coming from the throat. For vowel phones, handily, we don’t need the second two – the vocal chords are always* vibrating for vowels, and they affect the airstream the same way. In fact, that’s what makes a vowel a vowel: they do not hinder the airflow, they only shape it.

We’ll make up for this ease, however, by explaining where vowels are made with more detail. Consonants aren’t too tough — if we talk about, for instance, the phone [t], we can say that it’s alveolar (made by touching the tongue to the alveolar ridge) and that’s enough to figure out how the mouth should be shaped. But with vowels, by definition, the tongue doesn’t touch anything, even though it’s doing most of the work. So we have to get a little more creative in explaining where exactly the tongue is.

Good ol’ IPA chart again. For some reason we always draw mouth diagrams with people looking to the left. But in this case you have to imagine the person. Or do you???

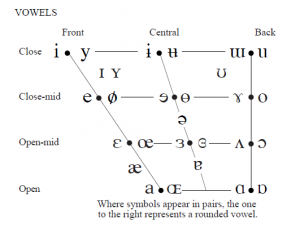

Not a lot more creative, though. The first way we describe vowels is as “front,” “mid,” or “back.” A front vowel is made with the tongue towards the front of the mouth, near the teeth. A back vowel is made with the tongue – waiiiiiiit for it – towards the back of the mouth. And a mid vowel… yeah. You got this.

The second way we describe vowels is as “open” or “close.” This refers to whether the tongue is low in the mouth, leaving most of the space open, or high in the mouth, making the space close. We have middling areas again here, called “close-mid” and “open-mid.”** So you can have a “close front” vowel, a “open back” vowel, or a “close-mid mid” vowel. You can also have the tongue right in the middle of the mouth, which we’ll come back to in a bit.

But once again, we’ve got pairs with the same tongue-placement, and this time it can’t be about voicing. What’s the diff between [i] and [y]?

Lips, baby.

When we make an [i], the sound of the double-e in “feet,” our tongues are high and forward, and our lips are flat. If you keep your tongue in the same place and make your lips into an O, you’ll have a [y]. You might recognize this as the instructions I gave a couple weeks ago for pronouncing Turkish ü — they’ve got the rounded counterpart to our [i] as one of their vowels.

Vowels are a lot of the reason that English is difficult to learn to read. The consonants aren’t so bad – the [t] phone is always* made by writing a <t> — but the vowels are peskier. A [u] phone can be spelled with <oo> as in “cool,” <ui> as in “fruit,” <ough> as in “through,” just <u> as in the short form “thru,” <ue> as in “blue,” <u_e> (that means <u>, then a consonant, then <e>) as in “duke,” <ou> in “you,” and even <o> in “do.” Worse, some of those spellings can indicate other phones, too. <oo> is [ʊ] in “book,” <u> is [ʌ] in “but,” <ou> is [ɑʊ] in “couch,” and <o> and <u> often get reduced to schwa.What’s a schwa? Well, I’m glad I rhetorically asked myself.

When words are made up of two or more syllables, we stress one of the syllables more than the others. The vowel in the stressed syllable is pronounced with the tongue decidedly in the front or the back, high or low. But in unstressed syllables*** the tongue tends to move towards the middle of the mouth. Then all the different vowels that we write end up sounding like that “mid mid” phone, the schwa: [ə]. So <a> is [ɑ] and <u> is [ʌ] and and <o> is [o] and <i> is [ɪ] in “father” and “ugly” and “cot” and “pig,” where they’re stressed, but they get schwa’d in “hella” and “support” and “undercover” and “perdition,” where they’re not. <e> is [e] in the first syllable of “elephant,” schwa in the second.

Alright. Enough about English. Next time, we put all this phonetics business to use and get to the really good part: phonology.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*As usual, when I say “always” I mean “except for some really weird bits and pieces, but dammit we can’t talk about every friggin exception when we’re trying to nail down the basics.”

**A lot of linguists go with “high/low” and “tense/lax” to describe this aspect of vowels. But we’ll stick with the IPA chart’s lingo for now.

***Just hangin at the beach, turned the phone off, glass of wine at hand, couple new mysteries to read… those syllables.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

Many of the same references as last week, plus check out this nice click-and-hear-it IPA chart. If you want to type all those little symbols yourself without having to hunt through Word for them, you can go here. And anybody who teaches pronunciation will have a section on the schwa, like pronuncian and the BBC.

And guess who has a new David Crystal book?

It’s MEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!

Spell It Out: The Curious, Enthralling, and Extraordinary Story of English Spelling is in my hot hands, and dang is that a good read. If you’re wondering why exactly we need a dozen spellings for each vowel phone, that is the place to look.

For more David Crystal awesomeness, check out this sweet as hell video of him reading Shakespeare in period-accurate English accent. Sweet. As. Hell.