Dear Language Nerd,

My nephew’s school is considering removing cursive script from the curriculum, and surprisingly many people feel very very strongly about it, on both sides. Care to weigh in?

Yours,

A. S. D. Curmeck

***

Dear A.S.D.,

I’ve never had to teach cursive myself, but I sure had to learn it, and the o’erwhelming impression left me through the foggy haze of memory is that vast chunks of my second-grade time could have been better used.

People mostly give two big reasons for hanging on to cursive. The first is to develop students’ aesthetics, their understanding and appreciation of beauty. The other is the practice in fine motor control. Cursive does hone the ability to both judge beauty and motor along, but it’s not the most efficient way to do either. I’ve heard it argued that cursive is as helpful for fine motor skills as learning an instrument — to which I say, awesome, let’s turn over cursive time to music class. Plus, bam, aesthetics there too!

There’s a third argument in favor of cursive, which comes up more rarely but which is more persuasive to me because, um, I am heavily biased. Without knowledge of cursive, upcoming scholars will have a harder time deciphering historical documents. The US Constitution, for example, was penned lovingly by Gouveneur Morris,* in beautiful cursive. It’s tough enough to read the original already, and as knowledge of cursive is lost it’ll only get tougher.

But ultimately that doesn’t convince me either — as a rule, the general populace can’t read ancient Greek, but the people who care about it learn it and transcribe the works into a form modern eyes can understand. Just like all other aspects of language, our script changes over time. I like cursive just fine, and have reasonably nice handwriting myself, but if it’s becoming a less useful skill, I say we chuck it. There are precious few hours in a schoolday already.

A pretty low percentage of our population seems to be invested in this topic (those some of those that are seem quite peeved). If you want to talk serious, country-wide emotion about scripts, you’ve gotta leave our fair language behind. First, let’s draw attention to a point that’ll seem a little odd to those who only write English: our cursive uses the same letters as our printing or typing. Cursive script is just a special way of writing the same alphabet. Losing it would not exactly be a sea change.**

Got that in hand? Good. Now let’s talk about China.

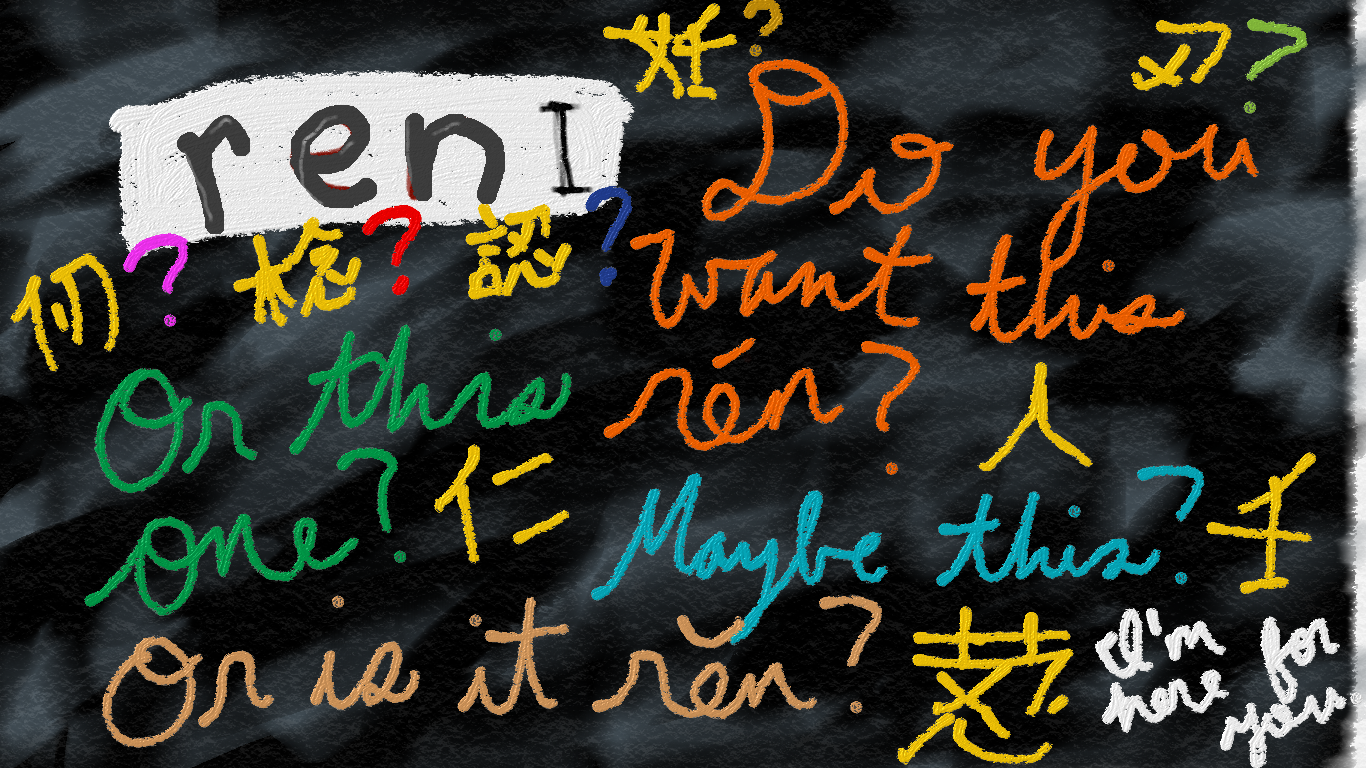

In Chinese, the writing doesn’t stand for sounds, like the English alphabet does. Instead, symbols stand for words or parts of words. “人,” for example, is a representation of a person, and “力” stands for power. This is handy for some things, like figuring out compounds — what’s 人力 mean? — but you have to know the pronunciation yourself.

So do Chinese computers have rows and rows of keyboards, to hold the thousands of symbols? No, because that would be hella ungainly. Instead, computers use a keyboard similar to an English one.*** You type in the sound of a word, and the computer will guess what you want, or send out a little drop-down menu with a list of characters with that pronunciation for you to choose from. Handy, innit? And it’s used in most phones for messaging, which carries this idea into constant, everyday communication.

But the effect of this technology is that, while people can still recognize plenty of characters, Chinese twenty-somethings increasingly find that characters they once knew are now trapped on the tips of their pens, as it were. And the upcoming kiddos know fewer still. Victor Mair refers to a “hemorrhaging of active charcter proficiency.” Now, this has nothing to do with the ability to compose, since only the writing system is affected, but that system is vanishing astonishingly fast. There’s an orthographic sea change for ya, and people are pissed.

So if you think losing cursive is a cause for concern, all right, just try to keep it in perspective.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*That’s not a misspelling of “governor,” that’s this classy man’s name. Tragically, he never became governor of anywhere.

**I had no idea that “a sea change” was from Shakespeare. That guy, always making up phrases and whatnot.

***There’s another kind of keyboard, called wubi, that’s based on the root shapes that make up characters, but from what I’ve read the pronunciaton-based style is much more popular.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

About 90% of the research for this article came either directly from the Language Log or from things they linked to there. Here are their articles about the loss of Chinese characters, and their links to other people discussing these changes. I say “their” — these are all by Victor Mair, but there are many other amazing linguists on the blog. Guys my point is the Language Log is consistently awesome, you should check them out.

The remaining 10% includes the specifically Constitution-related stuff – a fancy annotated type-up, and this Wiki on the Gouveneur. James Madison may have fathered the thing, but he sure didn’t set pen to paper. Plus, I don’t speak any Chinese, so I used the spiffy Mandarin Tools dictionary to check that my 人力example, taken from Japanese, worked in Chinese too.

[…] Cursives, Foiled Again! (theleagueofnerds.wordpress.com) […]

The best reason I can think of for teaching cursive is speed. Although I write in print most of the time, if I need to take notes or write quickly, I swap to cursive. It’s so much neater when I’m writing quickly, whereas print gets messy very easily when you write fast.

I write my notes in cursive as well, though my writitng is generally pretty messy no matter the style. But I think much of my generation is faster at typing than at writing either form of longhand.

[…] Cursives, Foiled Again! (theleagueofnerds.wordpress.com) […]