Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style is bad for writers.

This is an unpopular position, I know. Elements is beloved by literati, authors, English teachers, Supreme Court justices. Its precepts are in our stylebooks, our standardized tests, the air we breathe. People adore this book. I’m blaspheming.

I don’t care. It is a bad book. Why?

- Strunk is wrong.

I focus on Strunk because he wrote four-fifths of the book, and most of the problems are his. White wrote the introduction and the final essay on style, but most of what people absorb is Strunk.

Not every word Strunk wrote is wrong. Some of the style advice is golden, if explained more usefully elsewhere (for example, Zinsser. Because you know what isn’t a bad book? William Zinsser’s On Writing Well. More on that soon). But the occasional style advice nugget is about it. Strunk knew what he liked, but he didn’t have the linguistic knowledge to ground his ideas about grammar and vocabulary.

Better linguists than me have written thousands of words dismantling individual points from Elements – see the absurdly long works cited list below. Strunk is confused about passives. His grasp of “which” and “that” is iffy. He censures “hopefully” without cause. But these are stars within the larger constellation of his wrongness. Strunk is dead wrong about how language works.

Languages change. They change every day, every minute, every time its speakers open their mouths. Vocabularies change – words shift in meaning, new words spring up, old words shrivel. Grammar changes, more slowly. The sounds change. This is natural, normal, and unstoppable.

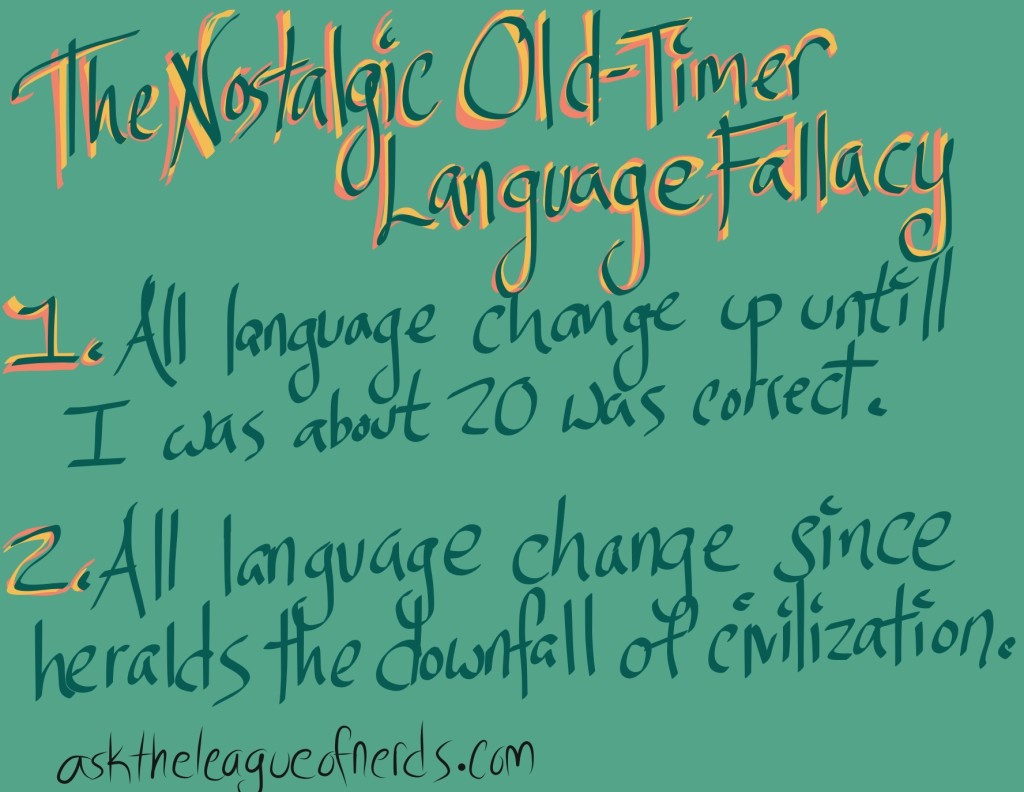

Few people make peace with this. From Plato on, we find that the next generation will ruin the language. Strunk was among the many who could not deal.

Strunk and White’s variety of English is not better than other people’s. They speak like wealthy old white men from New England in the early 20th century, and bully for them. But this very specific dialect is not by its nature more eloquent, more desirable, or more capable of communication than Southern English, or Black English, or the English that the current batch of tweens is inflicting on the current batch of old-timers.

Two people can use the same variety of English, the same grammar and words, and one be a literary genius and the other a terrible writer. Conversely, people using different varieties can astound equally: Toni Morrison, Mark Twain, Junot Diaz, Sparky Sweets. This is not a new idea. It’s obvious.

Perhaps the reason Strunk and White are so intractable in our culture is that this morass of grammar and vocabulary advice – not recommended – does disgorge the occasional timeless stylistic gem. Omit needless words is essential advice for all writers across time and space. Use the proper case of pronoun is not. “Whom” is dead. Let it rest.

Strunk tries to explain why his views are correct. But his justifications are capricious. Sometimes Strunk cites history:

“Transpire [is n]ot to be used in the sense of ‘happen,’ ‘come to pass.’ Many writers so use it (usually when groping toward imagined elegance), but their usage finds little support in the Latin ‘breathe across or through.’”

Sometimes Strunk does not know or does not care about history:

“They [is n]ot to be used when the antecedent is a distributive expression such as each, each one, everybody…”

…he says, not recognizing this as an older form than generic “he.” Sometimes Strunk cites modern usage: data, he decides, “is slowly gaining acceptance as a singular.” Sometimes Strunk scoffs at modern usage:

“If every word or device that achieved currency were immediately authenticated, simply on the ground of popularity, the language would be as chaotic as a ball game with no foul lines.”

Gee, what would have happened to English if Strunk had not arrived here to anoint himself umpire?

(It would’ve continued evolving and gotten along perfectly well, as it did for the thousand years before he showed up. And as it did anyway afterwards, despite his efforts.)

These are not reasons. They are justifications. Strunk likes some things and doesn’t like others. And that’s fine – everybody’s got opinions. But…

- Strunk’s opinions are decrees.

There is no humility in the first four-fifths of The Elements of Style. White recognizes this in the introduction, and calls it a virtue:

“[Strunk] had a number of likes and dislikes that were almost as whimsical as the choice of a necktie, yet he made them seem utterly convincing. […] He felt it was worse to be irresolute than to be wrong. I remember a day in class when he leaned far forward… and croaked, ‘If you don’t know how to pronounce a word, say it loud! If you don’t know how to pronounce a word, say it loud!’ […] Why compound ignorance with inaudibility?”

Well, Strunk’s book is full of ignorant, whimsical likes and dislikes, and he is shouting them at us. His opinions are not acknowledged as personal peeves and annoyances, but are given as orders not to be questioned or argued with – follow or fail. The section “Words and Expressions Commonly Misused” tells you in its title that if you are different, you are wrong. And it is nothing but a list of words, mostly words Strunk dislikes:

“Personalize. A pretentious word, often carrying bad advice.”

“Contact. As a transitive verb, the word is vague and self-important. Do not contact anybody[.]”

“Meaningful. A bankrupt adjective. Choose another, or rephrase.”

Or keep it, I suppose, and admit that you are bankrupt yourself.

William Zinsser has many of the same opinions on words as Strunk does – “disinterested” should mean “impartial,” “less” and “fewer” should be separate – but he declines the position of Language God. His equivalent chapter “Usage” (such a neutral title) consistently foregrounds his opinions as opinions. The chapter centers on his participation in the American Heritage Dictionary’s Usage Panel, which considers possible new words and definitions to be added. Zinsser tells us about the discussion, the debates, the other judges’ ideas, the times he changed his mind. Again and again he notes that this is a matter of taste. He explains his thought process to us, in detail, offering guidance for when you meet a new or changing word yourself.

I disagree with both Strunk and Zinsser, as it happens. “Disinterested” can do double duty as a synonym for “uninterested” while continuing with its quality work as “neutral.” And if “fewer” vanishes entirely and “less” is used for both quantity and number, fine by me. It works for “more,” it’ll work for the opposite.

I feel that I could explain this to Zinsser. Not change his mind or his writing – why should I want him to use these words exactly the same way I do? – but I could tell him my reasoning, and not be castigated for it. The overall effect of this chapter is empowering. He thought this, she thought that, what do you think? As long as you do think, you have a place in the discussion.

There is no responding to Strunk. Only his opinion counts. Disagree and be damned.

Zinsser’s humility is central to his writing in much the way that Strunk’s isn’t. But then, Strunk and Zinsser seem to me to have different goals.

- Strunk does not want to help the writer.

He wants to help the reader. White’s intro again:

“All through The Elements of Style one finds evidences of the author’s deep sympathy for the reader. [Strunk] felt that the reader was in serious trouble most of the time, a man floundering in a swamp, and that it was the duty of anyone attempting to write English to drain the swamp quickly and get his man up on dry ground, or at least throw him a rope.”

And that’s all well and good, except it’s not really “the” reader. It’s “a” reader, one particular reader, that Strunk so deeply sympathizes with – and that reader is Strunk. Strunk would like for you to write in exact accordance with his various whims and gripes, because that is most convenient for him.

Strunk never seems to even like the potential writer. He berates and mocks us into the one-man party line. “Like has long been widely misused by the illiterate; lately it has been taken up by the knowing and the well-informed, who find it catchy, or liberating, or who use it as though they were slumming.” White later adds that if we do not use “good English,” as they have defined it, perhaps it is because we are lazy.

Zinsser is always on the side of the writer. He is here to give you, o would-be writer, tools, tools that will last. His book is full of examples, funny examples, clever examples, clear examples of good writing and bad writing and how to turn the later into the former, examples his audience can connect to. “Our national tendency is to inflate and thereby sound important… But the secret of good writing is to strip every sentence to its cleanest components,” he tells us on page six. There follow so many examples, such careful direction, that when we reach page fourteen and find specific admonitions – “Beware, then, of the long word that’s no better than the short word… Beware of all the slippery new fad words… the word clusters with which we explain how we propose to go about our explaining” – when we reach these, we understand why he warns against them, and we can hunt out words and phrases that damage our writing beyond those specifically mentioned. There is no need to list every possible danger word. We have the skill.

The Elements of Style is called “the little book” – its shortness is its signature, and brevity is a virtue every writer aspires to. But all virtues can be taken too far. Strunk spends a total of four and a half pages on his most eternal, important advice, “Use definite, specific, concrete language” and “Omit needless words,” which is barely enough time for the aspiring writer to notice it, much less grok it. He then wastes 26 pages on admonitions about individual vocabulary words. He is giving you fish. Desiccated, sixty-year-old fish. Meanwhile, Zinsser is teaching.

This wouldn’t matter if Elements had remained one crotchety old-timer grousing about how kids today can’t form a proper sentence, or even one hoary professor requiring his students to write “forcible” instead of “forceful.” But the little book is enormously popular, and we suffer for it.

- Strunk has created a poisonous atmosphere.

The Elements of Style remains popular not because it is right, but because it is easy.

It’s not easy to write with. Following Strunk’s precepts is a difficult, unrewarding process. No. Elements is easy to criticize with. Easy to use to attack, to dismiss an idea with nitpicks of grammar and word choice, never needing to grapple with or even understand the target’s ideas.

Strunk and White’s decrees have been passed down, repeated, disseminated, what little nuance they once possessed stripped away. Even Strunk occasionally noted that words or grammar could be different in informal writing or speech. Tell this to the man I heard the other night correcting his frıend’s “who” to “whom” in a bar.

This does not affect us all equally. Strunk was, again, a wealthy old white man from New England in the early 20th century. The language he used and wanted reflects that. Are you or your audience younger, poorer, darker-skinned, from elsewhere? Prepare for scorn.

Zinsser notices this, though he does not blame Strunk and White (he admires them, and his own book is weakest when it slews toward their false star). People are afraid to write, Zinsser finds. They feel that they must write what their teacher wants, even long after their schooldays are over. He himself, reflecting on writing his book in a later essay, notes that he was uneasy putting his experiences into his book. “The reason was a fear of immodesty, born of the injunction that wasps shouldn’t ‘make a show’ of themselves. […] I never quite stopped expecting a knock at the door from the reticence police.” Perhaps the fear he felt can be blamed this time on White, whose admonishments of “Place yourself in the background” and “Do not inject opinion” have diffused into this general miasma of anxiety.

Zinsser’s On Writing Well is life-affirming, art-affirming. On finishing, you race to the keyboard, sure that you can share your message clearly and well, because he’s shown you how. On finishing Strunk’s list of “don’t-do-thats” you fear the keys. What if you make a mistake? There are so many to make. We are haunted by the ghosts of crankiness past.

Don’t live in fear of language. It’s yours. Take it.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

My two main references are surely obvious, but here are the links: Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style and Zinsser’s On Writing Well. And here is Zinsser’s other essay, Visions and Revisions.

None of this, by the way, reflects a low opinion of E.B. White’s actual writing. Using a skill and teaching it are separate things, and White was a master of his art. Even in Elements his bits are fun to read (“Do not dress words up by adding ly to them, as though putting a hat on a horse”). If you’re one of those who only know White from Charlotte’s Web, allow me the joy of introducing you to his works for adults.

Afterthought: Zinsser accurately describes my feeling towards Strunk and White on page 243. “It’s a universal impatience, whatever the category of old-timer, just as it’s a universal trait of old-timers to complain that their field has gone to the dogs.” Though to be fair, Zinsser himself indulges in a little old-timing in chapter 20. Kids These Days just don’t know elegance!

The collection and organization of the many articles explaining the inaccuracies of Elements has become so unwieldy that I am going to turn it into my next post. Hang tight.