Part 1 (A Matter of Some Consonants) is here.

Part 2 (Disemvoweled) is here.

Remember several thousand words ago when somebody asked me if all languages use the same sounds? And then I went and inventoried all the sounds that English has? Now finally – FINALLY – we can use that knowledge to contrast English with other languages.

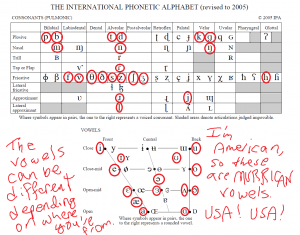

There are two main ways that a language can work differently from English. First, they can just have phones we don’t. (You recall, of course, that “phones” are a specific way of talking about sounds — we’ll contrast it with another way in a bit.) Here’s the consonant chart and the vowel chart, with our English buddies in red:

We’ve got a good number of phones, but there are plenty outside of our purview as well. In the first part of this series, we came across [q] and briefly [ɟ], which are phones in Arabic and Czech, respectively. Anywhere not circled s a possible sound that we’re missing, but which you can probably work out with a few lingual acrobatics. If you want a guide, check out this click-and-hear IPA chart.

As for the grey regions, well, I’ve had one embarrassing pharyngeal sprain this week, so I’ll leave further experimenting to y’all for now.

Now, it’s usually not necessary, but we can throw a lot more information onto a consonant phone than the three basics that we’ve been over.* There are a few reasons we might want to do that. Some folks out there just wanna be really, really, really specific when they look at how phones are made. Some want to contrast how similar phones are used in different languages. And some want to look at how allophones of one phoneme are used within a single language.

Wait, what?

Haha, allophones of one phoneme, the Language Nerd is just making up words, right? Nope.** Basically, we sometimes use slightly different phones, but we feel like we’re making the same sound. Take aspiration, which means having a (relatively) strong puff of air escape with a plosive. Put your hand in front of your mouth and say “kit” – air pops out with the [k], which means it’s aspirated. We can mark that with a little “h” in superscript if we feelin’ fancy, so [kh]. Now try again with “skit” – a little air escapes with [s], but almost none comes out with the [k]! Madness, right? Your mind is blown, right? Hell yeah it is.

The first is [kh], and the second is just [k], and they are different phones. But here’s the thing – in English, we don’t care. Unless you’ve been in a linguistics class before, you’ve never noticed the Case of the Double-K yourself. They both go into one big “k” category in our minds. That category is called a phoneme, and we write phonemes in slashes. So the phone [k] and the phone [kh] are both contained within the phoneme /k/.

This gets a little confusing, mainly because all the terms are so similar. Phones are the actual sounds we make, in all their complexity, and the study of phones is phonetics. Phonemes are the simplified categories that we use mentally to organize all these sounds and construct language, and studying them is phonology.***

You could feasibly cut phones into tinier and tinier pieces indefinitely. Aspiration is the difference between a notable puff of air and the absence of one, but what if you went further? You could have a lack of air, small puff of air, a medium puff, and a serious Big Bad Wolf. You could have super-small, small, kinda-small, medium, medium-large, and Grande. You could make a new breath size for every seven molecules. But at this point it’s getting pretty useless.**** If we want to make our phones work for us, we need to prefix them with “allo-.”

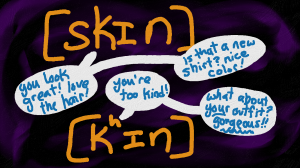

There’s more to the “kit”/”skit” difference than random chance. The same air and lack of air can be felt in “kin” and “skin.” Or “cat” and “scat” (where the <c> spelling is still /k/). When two phones work together like this – [kh] at the front of a word, [k] after /s/ — they are allophones. You don’t get [k] at the front of a word, or [kh] after /s/. The two phones are in complementary distribution.

All this, at long last, leads us to the second way a language can be different from English: it might have the same sounds as we do, but categorized in different ways. Korean does this with – you know what’s coming, right? – aspiration. There are two phones, [kh] and [k]. We use them as allophones of one phoneme, /k/. Korean uses them as two separate phonemes. [kh] is <ㅋ> and [k] is <ㄱ>.

We can be sure that Korean is doing something different with a simple test. We look for two words that differ only by the sound in question. In English, if you were to pronounce “skin” with a [kh] for some reason, people might think you were being weird, but they wouldn’t think you were saying a different word. They’d figure it out. In Korean, however, 코 [kho] means “nose,” and 고 [ko] is a totally different word, a particle that works kinda like “and.” 코 and 고make up a minimal pair, the most basic way of figuring out what phones a language uses as its building blocks.

We can use this to our advantage when learning a foreign language, but we’ll end up with a slightly goofy accent. (So, go for it if you’re visiting a country for a week. Learn your phones properly if you’ll be taking university courses and/or wedding vows.) Waaaaay back in the day, I wrote about the Korean alphabet, and transliterated <ㅋ> as <k> and <ㄱ> as <g>. Why? Well, <ㅋ> almost always comes at the beginning of a word, where English speakers will naturally pronounce it as [kh]. And <ㄱ> often comes at the beginning of a word too, but if I tell you it’s <k> you’ll go pronouncing it with too much air. There’s no voiced <g> sound in Korean, and since we pronounce that with much less air, it’ll be pretty close if you substitute it for unaspirated [k]. If you’re learning Korean as srs bznss, you need to learn how to throw unaspirated plosives around, but if you’ll just be living it up in Seoul for a few days, you can use /g/.

Wow, you now know a crapload about phonetics and phonology. Unless you stopped at the short answer back in part one, in which case, well, you’re efficient.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*Place it’s made, how it’s made, voiced/voiceless, if you skipped the first part. Which is cool, it’s not like I care or anything. …sniff…

***As some guy on the internet once wisely said, you hear phonetics with your ears, phonology with your brain.

****I’m always reading lists of quotes from people who made guesses about the future and were proven wrong immediately after (a world market for five computers, anyone?), but I feel pretty secure in this one. And if there are any seven-molecule theoretical phoneticians out there, I look forward to reading your research.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

Again, gotta cite Ole Miss and the IPA for this one. Looking for Korean examples has also led me to korean-flashcards.com and (back to) the absolutely stellar talktomeinkorean.com. And look, another sweet chart! I love a sweet chart.

Holy bejeebers that was a lot of phonology. NO MORE PHONOLOGY FOR A WHILE GUYS, ASK ME ABOUT SOCIOLINGUISTICS OR SOMETHING.

JUST… JUST NO MORE SOUNDS, OKAY?