Dear Language Nerd,

Do all languages use the same sounds?

-Sally Kimball

***

Dear Sally,

Short answer: No.

Long answer: Noooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo ooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo oooooooooooooo.

…

…..

…

All right, long answer with actual facts and stuff. But you asked for it:

We make language sounds by exhaling* air and then blocking or partially blocking that airflow in different ways. When we make a [b], for example, we stop the air with our lips. When we make a [k], we stop it with our tongue in the back of our mouth. When we make an [m], we stop air from coming out our mouth entirely, and send it through the nose instead. These three examples are from English, but you could stop air in ways that we don’t. For example, you could stop the air way in the back of your throat, at the uvula. That’s not an English sound, and if you make it near English speakers they might try to apply the Heimlich, but it totally is a meaningful sound in Arabic — ق.

Let’s jump on those square brackets real fast, because they’ll come in handy later. They’re there to say that we’re only talking about sound, not spelling.** When we want to talk spelling, we use triangle brackets, <>. It doesn’t matter that <friend> is written with an <f> and <phylactery> is written with a <ph>, the sound is the same and so they get the same symbol , [f]. These language sounds that get written inside square brackets are called “phones,” because just calling them “sounds” would be too easy, I guess.

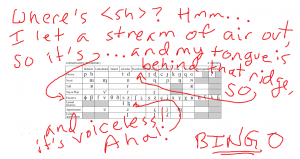

So how many phones are out there, exactly? Well, it’s hard to say, but this is a good place to start:

This is the current chart of the International Phonetic Association, called the IPA chart. It is not the end of the story – just like the highlight of a biologist’s life might be discovering a new kind of bird, research phoneticians would be ecstatic to discover a new phone and upend the chart and then have to make a new chart and maybe name it after them? I mean, if you insist. At the very least, they dispute each other over the details, and then the chart gets revised.

But the IPA chart does help us talk about most of the phones in most languages, and we can certainly cover English with it. To start out, let’s talk about that top part, where what we English-speakers would think of as “regular consonants” hang out. The table is organized to help you figure out what phones the symbols in the middle represent – the words in the top row tell you where in the mouth you’re blocking the airflow, and the words going down the left side explain how the airflow is being changed. Let’s take the top first.

Bilabial: This one is easy to decode. “Bi” means “two,” and “labial” means “lips.” So sounds you make by flapping your lips around.

Labiodental: Also not too tough. “Lip” again and “dental,” meaning “teeth.” Specifically your upper teeth and lower lip. I mean, I guess you could make an [f]-ish sound with your lower teeth and upper lip, but it’s gonna be weird.

After this, the tongue gets involved, but it’s so usual that we don’t bother adding a Latin prefix for it. Assume tongue until told otherwise! (Warning: this is not actually a wise motto to apply to other areas of your life.)

Dental: Tongue on teeth. What kind of dumb language would make a sound on the teeth? Oh wait, basically just us.

Alveolar: Tongue on the alveolar ridge, which is the big lump of gums that your upper teeth are stuck into.

Postalveolar: Right behind the same ridge, at the front of the roof of your mouth.

Retroflex: The tongue is near the postalveolar area, but doesn’t touch it – instead, the tip of the tongue curls backwards.

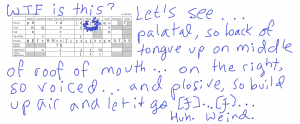

Palatal: Tongue on the palate, the middle of the roof of the mouth.

Velar: Back of the tongue on the velum (or soft palate), which is the back of the roof of the mouth.

Uvular: The back of the tongue hits the uvula, the dangly thing in the back of your mouth.

Pharyngeal: The pharynx is the bit of your throat where everything comes together – the nasal and mouth cavities at the top, and the pathways to the lungs and stomach below. This is so far back that the very root of the tongue has to push backwards to affect the air. Not found in English, or many other languages either.

Glottal: Way, waaaay down the throat, at the opening of the vocal chords. This one does not get hit by the tongue. If you have attempted to make a consonant by hitting your glottis with your tongue, you are excused from reading the rest of this post as your make your way to the hospital. The rest of us, however, can shrink the opening a bit and make an [h].

Alright, still hanging in there? Let’s get the left-side words.

Plosive: As in “explosive.” This is when you stop the air completely, let it build up, and then release it in what can be very generously described as an explosion. [b], [t], and [k] are all made this way.

Nasal: Shut your mouth and open your nose! [m], [n], and [ŋ] hang out here.

Trill: Not used in English, this is how you make a fancy Spanish rolled r, which is in fact [r] on the chart. Our English r is an approximant, see below, maybe four inches.

Tap or flap: This is like a really light, really fast plosive. When we say a word like “butter” or a phrase like “at all,” we don’t go to all the trouble of stopping and building up air to make a serious [t] sound. We’re busy, ok? Instead we make a single perfunctory motion towards the alveolar and then get on with our lives. That’s this little guy: [ɾ]

Fricative: This is a way of partially, not completely, blocking the airflow. [z] is made in the same place in the mouth as [d], but we stop the air for [d] and don’t totally stop it for [z]. We annoy the air, but we let it out.

Lateral fricative: “Lateral,” here and below, means that air is stopped from going down the center of the mouth but allowed to go around the sides. We don’t have any lateral fricatives in English, but we’ll come back to the idea of laterals in two shakes.

Approximant: Approximants are barely even consonants at all, and some of them, like [w], arguably aren’t. You barely mess with the airflow at all, and are almost just shaping it (if you’re only just shaping it, you’re making a vowel). The English r, which takes the phonetic symbol of upside-down [ɹ], is here.

Lateral approximant: Here’s our lateral! When you make an [l], your tongue hangs out in the middle of your mouth, but air goes around it at the sides.

“Wait a minute!” you say now, rising from your seat, monocle popping off and flying about the room. “Wait just a gosh-darned hootin-tootin rama-lama minute! There are two bilabial plosives here, [b] and [p]! And yes, they are both made by compressing the lips and allowing air to build up and then to burst out in what really cannot be reasonably deemed an explosion, but what use is this chart if it cannot distinguish between these decidedly different letters? Answer me THAT, hmmmmmmm?”

Take just a sec, couple deep breaths, count to ten, find your monocle, and we’ll talk about voiced and voiceless pairs.

Your vocal chords are in your larynx, right below that dangerous glottis. If you tense them up, when you let air go past them they vibrate. So many phones in English come in pairs – one with the vocal chords vibrating, one not. In the IPA table, the non-vibrating or voiceless phone is on the left. We also have lots of sounds that are voiced but don’t have a voiceless friend, like the nasals and the approximants. We’ve got just one sound that only comes voiceless, and that’s [h].

Alright, let’s take a look at that table again. Seem more meaningful now?

Or conversely:

Now we’ve got some building blocks to talk about sounds with. But there’s another monocle-endangering moment just waiting to happen — some of our letters are missing, and others are up there under the wrong phones! I mean, since when is <q> uvular? Since never, that’s when!

Well, <q> makes a [k] sound***, and not having two letters represent the same phone is kinda the whole point of the chart. And there’s only so many letters on the keyboard, so um, since you weren’t using it, we thought we’d just take it for that uvular Arabic phone I mentioned up in the first paragraph, okay? We cool?

Once we get past that stage where we think elemenopee is one letter, we all know that we’ve got 26 letters in the English alphabet. But some of these written letters aren’t unique phones, like <q>. Or like <c> — it makes the same sound as either [k] or [s], so it’s redundant. And well, that’s two out of three, so let’s mention <x>, which usually makes the sound of [k] + [s] (as in “fox”).**** Even more important, we use other phones in speaking that don’t get their own special letter, like <sh> and <ch>.

So these guys make the same sounds on the chart that we would expect them to, based on their usual role in English:

[b], [p], [m], [f], [v], [t], [d], [n], [s], [z], [l], [k], [g], and [h]

[w] does too, but it’s not on the chart.

<C>, <q>, and<x> we think of as unique consonants, but they get spelled in IPA with other letters because they’re not unique sounds. Conversely, there are 6 other English sounds that we use in speaking but that don’t have their own letters. They do get their own symbol on the chart, though:

<ng> is [ŋ] (more on [ŋ] here)

The almost-z sound in the middle of “pleasure” is [ȝ]

Voiced <th> is [ð]

Voiceless <th> is [θ] (and more on those two here)

<sh> is [ʃ]

And <ch> is [ʧ], because it’s what happens if you say [t] and [ʃ] together.

Seriously, say [t] and [ʃ] at the same time. Seriously! It works.

Finally, there are three oddballs. <r> we talked about above – [r] is taken by Spanish, so we get [ɹ]. But honestly, if you’re only discussing English in your research paper or whatever, you can probably get away with writing [r] and no one will care. You can’t pull that with <y> — it gets [j] on the chart, because in some other languages <j> makes the sound that our <y> makes in <you>. Since <y> gets [j], <j> can’t have it. Instead <j> gets the fancy [ʤ], because just like how [t] + [ʃ] = <ch>, [d] + [ȝ] = <j>. Hmm, could those be voiced and voiceless sets, right there? Why yes, yes they could.

Cool! So that’s all the important sounds, and we can go on to talking about how languages use them, right?

Wait! VOWELS!

Sunuvabitch.

Next time.

Yours,

The Language Nerd

*Or, in a few odd cases like clicks, inhaling.

** I know in the past I’ve told you to put sounds inside slant brackets, / /. That was for talking about sounds in a slightly different way. All will be clear by the time we finish this series, I promise.

***So <qu> is [kw].

****What is up with [k] and [s]? Why do we have so many ways of writing those two phones, while [d] gets just the one? Friggin divas, man.

Got a language question? Ask the Language Nerd! asktheleagueofnerds@gmail.com

Twitter @AskTheLeague / facebook.com/asktheleagueofnerds

I took excellent phonetics courses at the University of Mississippi, which sadly does not post much course info to the public. All these universities do, though! Plus this, which is not by a university but just some super cool guy! The internet, it is the best.

This one notably includes slightly more scientific drawings of where each phone is articulated in the mouth. And this one is taught by Mark Liberman! Mark Liberman! Do these undergrads realize how lucky they are?

Also neat is WALS, the linguistics map site I’ve referenced before with their cool color studies. Here they’ve got a map of languages with weird sounds, including pharyngeals and “th.”

And last but not least, the IPA! I <3 you guys, I super heart you.

[…] Part 1 (A Matter of Some Consonants) is here. […]

[…] Part 1 (A Matter of Some Consonants) is here. […]

[…] “y” sound we pronounce it with, “yoo-nee-corn.” Or /’junɪkɔɹn/, if you read the phonology posts. Similar for “a European” or “a one-way […]

[…] accent is slow come from? Well, this is more guesswork than I like, but my research turned up three phonological (sound-based) reasons, things that might lead to this impression just a […]

[…] Alphabet, which is weird, because it is not phonetic at all. I’ve talked in previous posts (at length) about the International Phonetic Alphabet, which actually is phonetic. Here’s the difference: […]

[…] I’ve talked about at some length, here. It’s the sounds of a language. What sounds do the speakers use to make words? Not every language […]

Hi, just your average internet denizen here. I stumbled on your blog earlier and haven’t been able to get off it since! It amazes me how you consistently take a complicated subject and make it so understandable. Truly excellent writing. I’ve already learnt hangeul, the nato alphabet and now begun picking up the IPA—and that’s just today! Honestly, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to find good information on linguistics on the net, and yours is some of the best!

Many thanks for the good work!

Thank you so much! That means a lot to me — I’m just doing this for the love of linguistics, trying to share what I care about, so I’m glad something’s clicking. Now I feel all warm and fuzzy inside. Happy New Year!

[…] make three different sounds here, which I’mma go over with that International Phonetic Alphabet we learned that one time, because damned if this ain’t just what it’s for. For these folks “merry” has the vowel /e/ […]